CHAPTER SIX: The Superintendent’s Lodge and Other Buildings

Photos · Additional Resources

Photos

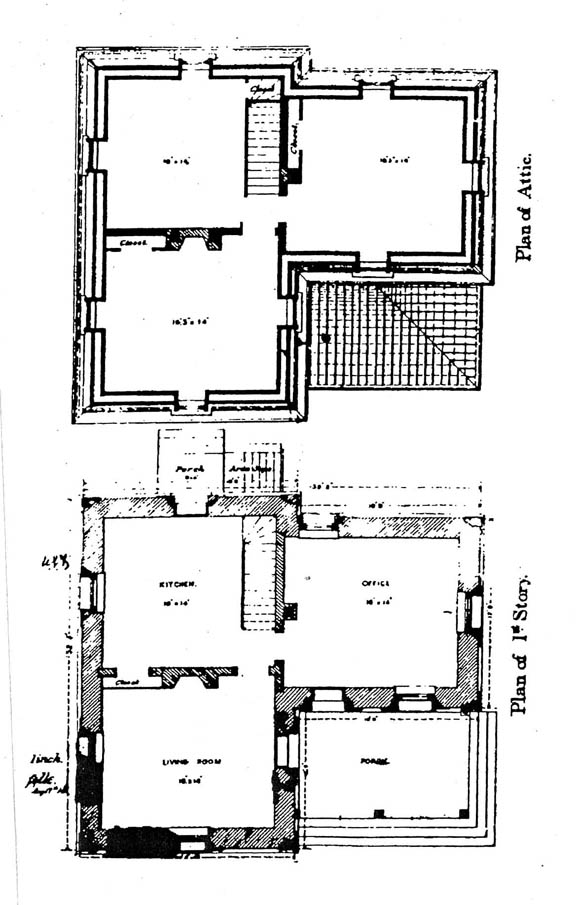

Like most national cemeteries in the country, Fredericksburg’s superintendent’s lodge closely follows a design put forward by architect Edward Clark. Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs approved Clark’s plans in 1871.

* * *

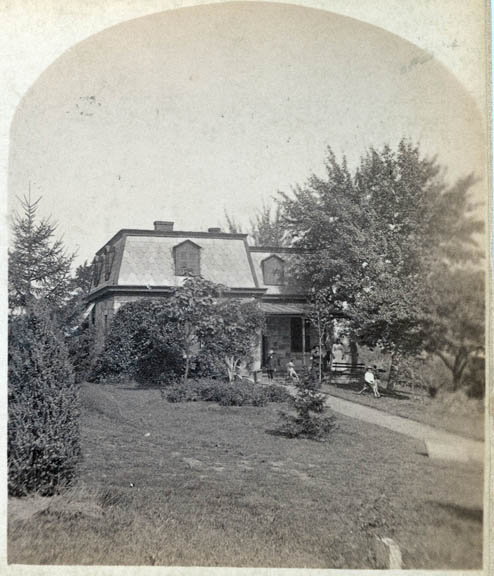

This photograph of the lodge was taken ca. 1883. Around the porch of the building are two women and three children. The Caucasian woman dressed in black appears in at least two other images taken at the same time. She is almost certainly the superintendent’s wife. The black woman is undoubtedly a nanny or housekeeper.

* * *

Two modern images of the cemetery lodge, one taken from the southeast, the other from the southwest:

* * *

This sketch of the cemetery’s buildings dates to about 1874. At left is the carriageway bordered by the greenhouse (G.H.). The lodge (L.) and tool house (T.H.) are farther to the right. The large circle between the lodge and the tool house depicts a cistern, which supplemented water supplied by a well (W.) situated near the northeast corner of the property.

* * *

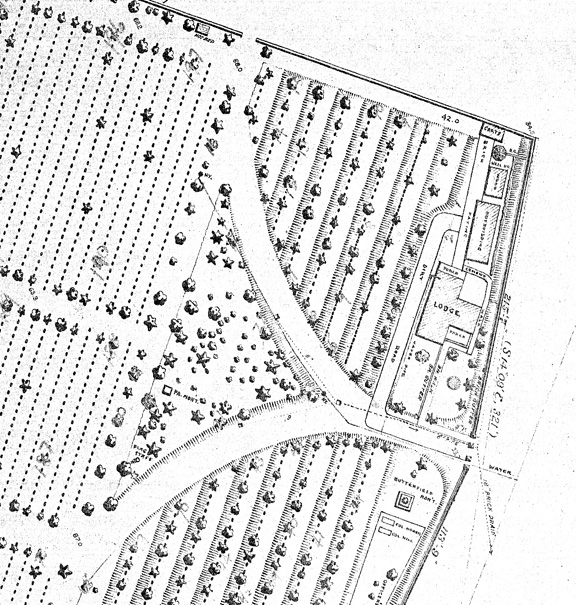

By the time this plat was made in 1911, the greenhouse had been removed and the wooden tool house had been replaced by a brick maintenance building, labeled here as “outbuilding. A woodshed and cart house had been added by that time and the well had been covered. Other changes to the property included the addition of a rear porch on back of the lodge, construction of the 127th Pennsylvania and Fifth Corps monuments, and the removal of the flagstaff to its current location at the brow of the hill. Officers Row had been created, although it contained but two graves: those of Lieutenant Colonels Edward Hill and Thomas Morris. Note the water pipe running up the carriageway and dividing at the grassy triangle, the truncated maintenance road, and the hot bed located just west of the side gate.

* * *

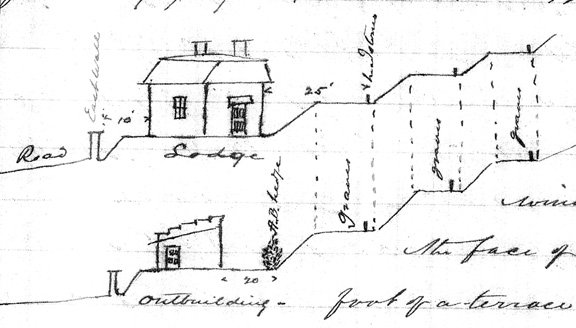

This profile of the cemetery, drawn sometime after 1881, includes rough sketches of the superintendent’s lodge and the brick maintenance building with its sloping roof and side door.

* * *

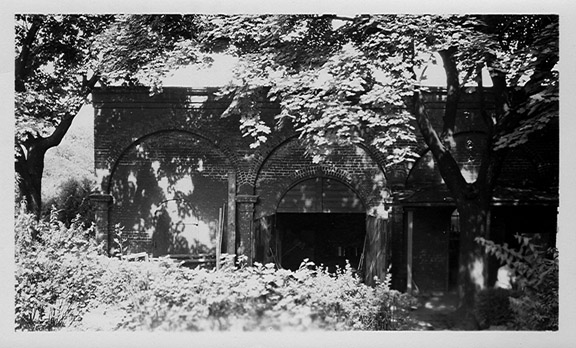

A view of the front (west side) of the brick maintenance building showing the three bays.

* * *

The back (east side) of the maintenance building is visible in the background of this 1930s photograph that shows the Civilian Conservation Corps rebuilding the south end of the Sunken Road’s famous stone wall. By that time, a screen had been added to the lodge’s porch.

* * *

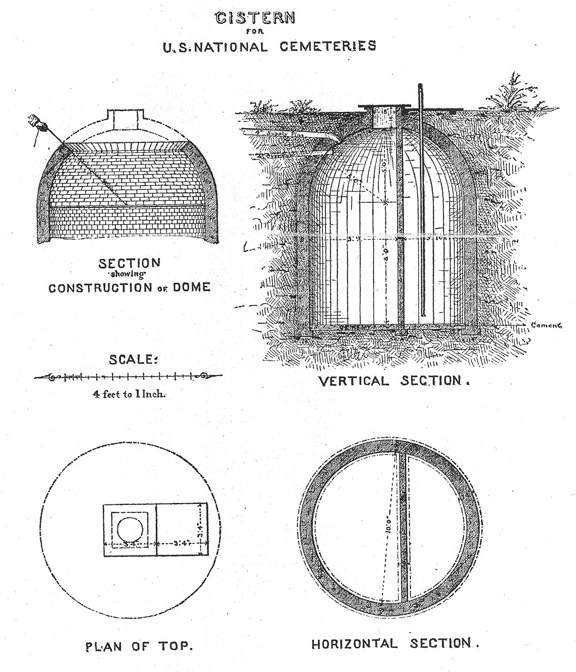

Cross-sections of the type of cisterns constructed in national cemeteries throughout the country.

* * *

The Quartermaster Department added a cellar to the cemetery lodge in 1929. A concrete stairway on the north side of the house led to the underground chamber on the outside. On the inside, residents could access the cellar by a wooden stairway that ran directly under the main staircase. After the National Park Service took over the cemetery, the interior stairway was removed and a closet was put in its place; however, the interior stairway is still evident in the cellar itself.

Additional Resources

Lodge Improvements

The lodge had windows on both the first and second floors. The first-story windows had shutters. The second story had shallow dormer windows that extended forward from the sides of the Mansard roof. Framed in gabled casemates, they had no shutters. Dark paint covered all of the exterior woodwork in the 1870s, but by the 20th century that had changed. By the early 1900s workers had added dark shutters to the second-story windows and had painted the rest of the exterior woodwork white. In addition, workers painted decorative diamond-shaped figures known as lozenges beside each second-story window. The lozenges disappeared by World War II.

For most of the lodge’s history, wallpaper decorated the walls. The Army papered the office at an early date, and Charles Fitchett papered the remaining first-floor rooms at his own expense in 1882. By 1888 every room in the house had been papered, although not with the best of taste. Inspector W. H. Owen bluntly expressed the view that most of the rooms had received “an inferior & ugly paper,” some of which was torn and had to be replaced. “I do not think the papering of the walls of lodges should be permitted,” he wrote in sweeping condemnation. “The paper put on, so far as I have seen, is inferior, soon peels off and has to be renewed at much greater cost than kalsomine or even paint. Once papered there is no way to repair except by repapering.” The Department paid no attention to Owen’s opinion and continued to paper the lodge for the next forty years. By contrast, the interior woodwork was always painted, and in 1886 the first-floor woodwork was grained.

Like all structures, the superintendent’s lodge required constant maintenance. Exterior woodwork rotted, gutters and downspouts leaked; slate tiles cracked. The Army repaired the lodge, as needed, and occasionally made small improvements. In 1886 it placed a hood over the chimney to prevent it from smoking, and in 1888 it added a skylight over the second-floor landing to illuminate the dark stairway.[1]

Two sets of stairs led to the basement: an interior stairway made of wood and an exterior stairway made of concrete. The interior stairway stood directly below the steps leading to the second floor in a space today occupied by the first-floor coat closet. The exterior stairs bordered the north wall of the building’s east wing and are still in use.

————

[1] Anonymous, 1882 inspection report, FNC3; James Gall, 1883 inspection report, FNC4; W. H. Owen, 1886 and 1888 inspection reports, FNC1; Letters Sent, pp. 48, 138, 149. In 1882 inspectors proposed adding a ventilator to the second floor, but it is uncertain whether this was done.