A Picnic Amongst the Dead

Today, we are pleased to welcome back guest author Mike Block

Growing up, like most children of the sixties, I was in front of my 26-inch color console TV on Saturday mornings, watching cartoons, particularly The Bugs Bunny Show. One of these cartoons featured Ralph E. Wolf and Sam Sheepdog. “The series is built around the satiric idea that both Ralph and Sam are just blue collar workers doing their jobs,” one writer reminds us. “Most of the cartoons begin at the beginning of the workday, in which they both arrive with lunch pails at a sheep-grazing meadow, exchange pleasant chitchat, and punch into the same time clock. Work having officially begun with the morning whistle, Ralph repeatedly tries very hard to abduct the helpless sheep and invariably fails. Sam (he is frequently seen sleeping), always brutally punishes Ralph for the attempt. At the end-of-the-day whistle, Ralph and Sam punch out their time cards, again chat amiably, and leave, only to come back the next day and do it all again.”[1]

After the Battle of Cedar Mountain, incredibly something very similar occurred. Americans, committed to defeat and destroy other Americans, clocked out of war for a time and had for a picnic. They laid down their arms for several hours on a hot Monday and joined together on a battlefield filled with dead and wound men to reacquaint themselves with past friends and comrades in arms, swap stories of adventure, and speculate on how the greater world would view recent events. The results of this encounter resonated for the next twelve days at locations in Culpeper, Orange, and Fauquier Counties.

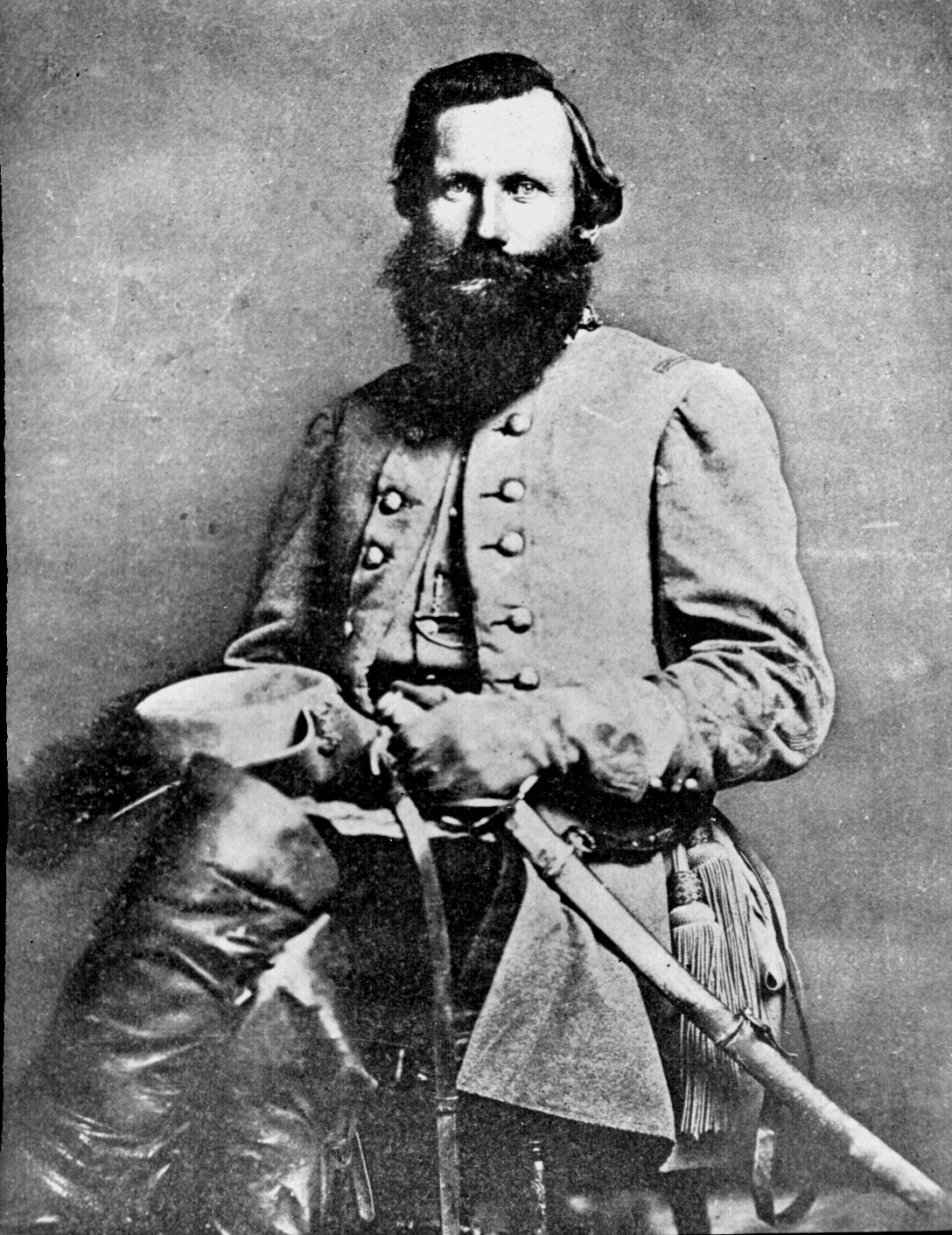

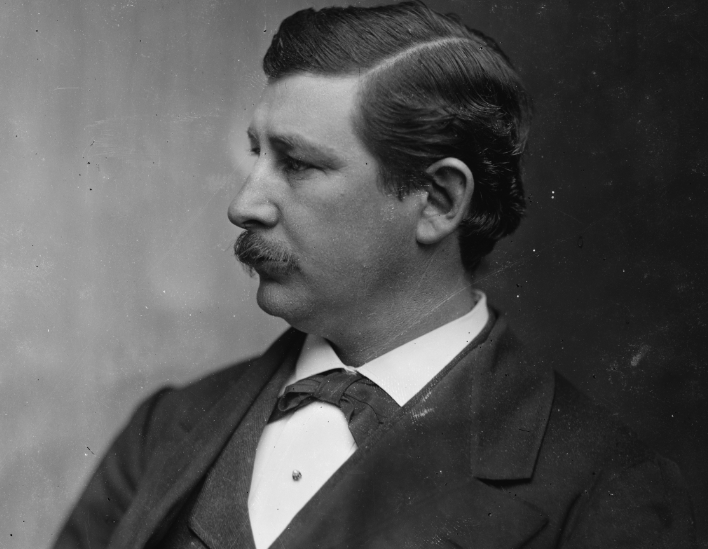

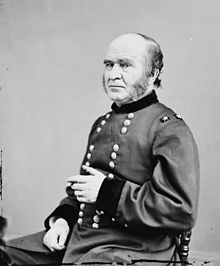

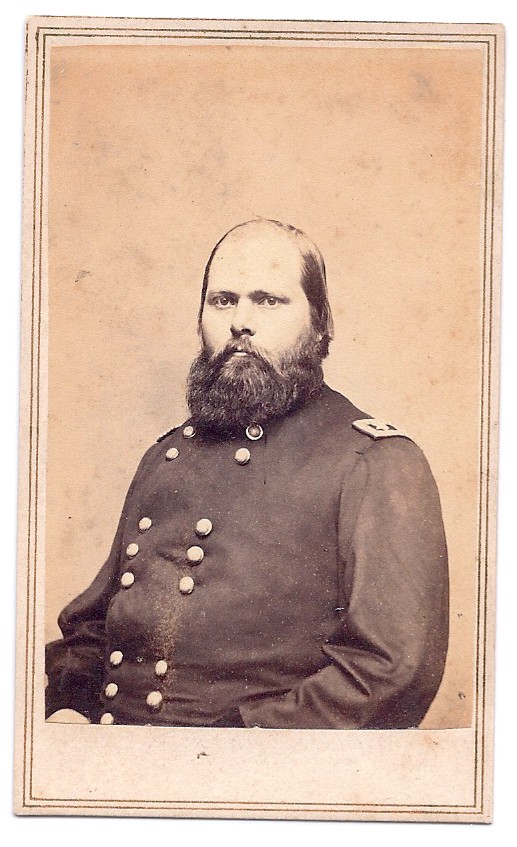

Two days after the battle, August 11, 1862, a truce was declared and elements of Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Army and John Pope’s Army of Virginia returned to the rolling fields to recover any remaining wounded and bury the dead. The truce was overseen and managed by two Confederate and two Federal officers. The Confederate administers of the truce were Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, who arrived on the field the day after the battle, and Brig. Gen. Jubal A. Early. For the Federals, the truce was managed by Brig. Gen. Benjamin S. Roberts, Pope’s chief of cavalry, and Brig. Gen. George L. Hartsuff. What made the scene more of a social setting rather than opposing armies warily watching one another was that Stuart and Hartsuff were West Point contemporaries. Hartsuff graduated in 1852 and Stuart two years later. Stuart sought out Hartsuff and, according to correspondent George Townsend, “the pleasantries flowed freely and they took a quiet turn together, speaking of their old school days, perhaps.” When they returned, “a bottle of whiskey was produced, out of which all the General’s drank, wishing each other an early peace.” [2]

The group was joined by Lt. Col. David Strother, Pope’s cartographer, and after a short while, Brig. Gens. Samuel W. Crawford and George Bayard joined the expanding group. They came prepared, however, and brought a basket of eatables, which everyone enjoyed. Crawford and Bayard were both pleased to see their old prewar companion “Jeb,” and the group began to swap stories of previous exploits. The banter was described as “boyish”—boyish banter amidst the dead and dying. “During the talks something was said about the yankee papers claiming every battle a victory,” wrote Charles Blackford, “and Stuart bet Crawford a hat in my presence that the yankee papers would claim this battle a victory for the Federals.”[3]

The bet was made and, a few days later under a flag of truce, Crawford was obliged to pay off. A package was passed through the lines, now on the south side of the Robinson River in Orange County that included a copy of the New York Herald trumpeting a Yankee victory and a new hat for Sam’s friend, Jeb.

Stuart wouldn’t keep the hat for long. On the morning of August 18, he was sleeping on a front porch in Verdiersville, in Orange County, awaiting the arrival of Brig. Gen. Fitz Lee’s brigade of cavalry. He awoke to the sound of approaching cavalry, but unfortunately, it wasn’t Lee, but a Federal cavalry column. Stuart and his staff quickly scattered to the four winds, escaping the fast-approaching Yankees. Captured in the scramble to get away was one adjutant, Major Norman H. Fitzhugh. Regrettably, Fitzhugh carried Confederate dispatches that would reveal to Pope Robert E. Lee’s intentions. That knowledge allowed the Federal army to successfully withdraw to the north side of the Rappahannock River.

Also lost in the haste to escape was Stuart’s recently won hat along with a cloak. Embarrassed, the bold cavalier spent the day wearing a handkerchief around his head and was constantly asked in jest throughout the day, “Where’s your hat?”[4]

Stuart vowed revenge and would get it just a few days later at Catlett Station along Cedar Run. Stuart rode behind Pope’s lines and attempted to burn the railroad bridge over the run. A heavy thunderstorm thwarted the destruction of the bridge, but Stuart did capture much of Pope’s headquarters baggage and dispatches. Among the spoils that rainy August 23 was John Pope’s great coat.

Stuart safely returned back across the Rappahannock River and, two days later, another note was sent through the lines. This timeStuart was the sender, and he addressed his note to Pope. “General: You have my hat and plume, I have your best coat. I have the honor to propose a cartel for the fair exchange of prisoners.” Stuart received no reply to his proposal.[5]

The hat, coat, and the personal notes quickly passed to memory,as realities dictated a renewed focus on war. The plains of Manassas were a few short miles and days away.

The war is greater than a hat, a cloak, or a picnic lunch. But I have always found it uniquely interesting that in the midst of the carnage of the Civil War that time was found again and again for old friends and comrades, now enemies, to pause and acknowledge each other, inquire about health, and provide and care for, in life and death. Examples abound. Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock with recently captured Maj. Gen. Edward ‘Alleghany’ Johnson and ‘Maryland’ Stuart at Spotsylvania. Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer and his mortally wounded classmate Stephan Dodson Ramseur at Cedar Creek. The returning of the mortal remains of Maj. Gen. Phil Kearney after the brief and violent encounter at Ox Hill. And in Culpeper, a picnic in the midst of the dead on the Cedar Mountain battlefield.

For a brief time, like Fred E Wolf and Sam Sheepdog, American warriors got along.

————

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ralph_Wolf_and_Sam_Sheepdog

[2] Townsend, George Alfred, Campaigns of a Non-Combatant, 1866, (USA, Time-Life, USA, 1982), p 275.

[3] Blackford, Charles Minor III, ed., Letters from Lee’s Army (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1947), p 111, Blackford, William M., War Years with Stuart, (New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1945),p 98,

[4] Hennessy, John J., Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas, (New York, Simon and Schuster, 1993, p 48.

[5] Hennessy, p 79.

Ralph sure looks like Wiley Coyote to me, which might fit with JEB Stuart. Not sure who Sam would be although he does resemble Ben Roberts a bit.

Great article, Mike. Thanks for writing it!

Sam, you are very welcome. It is interesting how little incidents create running narratives, big and little

Great story,Mike. Please keep finding and telling the stories of the battle of Cedar Mountain. Diane