Disease: A Tale of Two Regiments (Part 1)

We are happy to welcome back guest author Jim Sundman

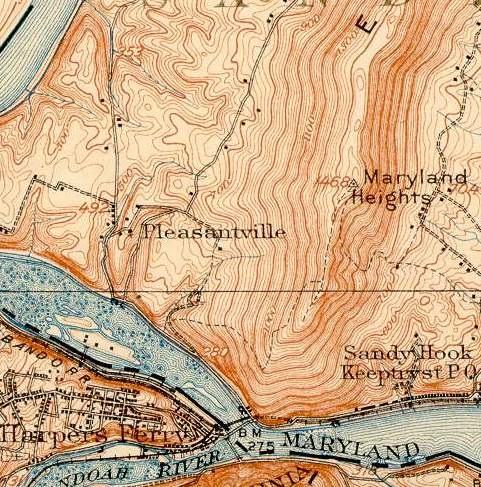

On October 1, 1862, Corporal Joseph Couse of the 107th New York regiment died of “brain fever” while his unit was encamped on Maryland Heights across the Potomac River from Harpers Ferry. A farmer from the small town of Hector in upstate New York, Couse was the first man in the 107th to die from disease during the war. With no coffins available, a sergeant in his company (and carpenter by trade) hammered together a “rough box…of old fence boards” in which to bury Couse.

About three weeks later on October 20th, Private Martin V.B. Demarest of the 13th New Jersey regiment died from “intermittent fever” on Maryland Heights, being one of the first in his unit to die from disease. The twenty-one year old carpenter from Paterson, New Jersey married Hannah Masters before enlisting that summer. Demarest’s seventeen year-old bride was now a widow. Their child was born the following year.

The 107th New York and 13th New Jersey were just two of the many new regiments organized during the summer of 1862 in response to Lincoln’s call for 300,000 additional Union troops. The 107th began recruiting in June from Chemung, Steuben, and Schuyler Counties in upstate New York, and by mid-August the regiment had a full complement of over 1,000 officers and men. They were mustered into service of August 13th and arrived by train in Washington, DC two days later. The 13th New Jersey on the other hand (whose men came mostly from Newark, Paterson, and Jersey City, along with a handful from New York City), got a later start in recruiting. They weren’t mustered into service until August 25th and arrived in Washington, DC on September 2nd. The rolls of the 13th had about a hundred less men than the 107th.

As both regiments arrived in the nation’s capital, they were promptly sent across the Potomac to Arlington Heights for more training. However, their days digging trenches, constructing earthworks, and constant drilling on the Virginia soil did not last long as the Union Army set out in pursuit of Lee who crossed into Maryland on his first invasion of the north following his victory at Second Manassas. On September 8th, as the 107th New York and 13th New Jersey were marching into western Maryland, both regiments were brigaded together along with the veterans 3rd Wisconsin, 2nd Massachusetts, and 27th Indiana to comprise the Third Brigade of the First Division of the Twelve Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

The Third Brigade, including the green New Yorkers and Jerseymen, were actively involved when the Union and Confederate armies met on September 17th in the fields and woods near Antietam Creek just outside of Sharpsburg, Maryland. Both units suffered dozens of casualties on the northern part of the battlefield that day including 10 men in the 107th New York and 19 in the 13th New Jersey who would die from battle wounds. General Alpheus Williams who took command of the Twelve Corps after the death of General Joseph Mansfield made special note of the two new regiments in his official report:

The One hundred and seventh New York, Colonel Van Valkenburgh and the Thirteenth New Jersey, Colonel Carman, being new troops, might well stand appalled at such exposure, but they did not flinch in the discharge of their duties. I have no words but those of praise for their conduct. They fought like veteran soldiers, and stood shoulder to shoulder with those who had borne the brunt of war on the Peninsula, in the Shenandoah Valley, and from Fort Royal to the Rapidan.

After Antietam, the Twelve Corps remained in Maryland. The 107th New York, 13th New Jersey and the rest of the Third Brigade went into camp across the Potomac River from Harpers Ferry on Maryland Heights, where they occupied a piece of farmland on a plateau on the west side of the ridge. Neither unit would see action again until Chancellorsville in early May 1863, more than seven months later.

Both regiments were initially without shelter on Maryland Heights (the wagons containing their tents and other accoutrements turned back to Washington as they marched into Maryland), but the weather for the most part remained warm and dry. “The weather has been remarkably fine and well it is so, or my men without any protection from the storms would suffer much from exposure,” the 13th’s Colonel Ezra Carman wrote in his diary in early October. Private Sebastian Duncan of the 13th received a blanket in the mail from his sister but wrote to her on October 1st that “I have not suffered from the want of it as we have had no rain of any consequence since the fight and with the exception of two of three nights, it has not been cold.”

But everything would soon change. The men’s tents had not yet arrived as the weather turned cold and rainy. “I have never been more annoyed at the weather any where in my life,” the 13th New Jersey’s surgeon, Dr. John J.H. Love wrote to his wife back in Bloomfield. Colonel Carman also made note of the change in his diary on October 12th: “All night the rain came down slowly and surely on my tent above me and it made for me a sleepless night occupied as my mind was with anxiety for my 700 men without shelter save that scantily furnished by their brush huts which cannot shed a heavy rain.” Some soldiers made due with what they could. The 13th’s Private Joseph Crowell later wrote that during a period of constant rain on Maryland Heights that he “did not think there was ever more suffering and discomfort experienced by a body of soldiers during the whole course of the war.” During the deluge, Crowell and another soldier used two boxes to cover their heads: “To be sure the rest of our bodies were outdoors, drenched to the skin, but our heads and faces were protected and we pitied the other fellows who had no nice boxes to protect themselves with!”

In addition, food provided to the men on Maryland Heights (as was often the case during the war), was inadequate, causing some to forage the countryside or knock on the doors of local homes for additional sustenance. “Just now one of my Corporals brought me some hard bread as a sample of what they had to eat and on breaking it open I found it was alive with bugs and worms!!,” the 107th’s Captain Newton Colby wrote to his father back in Elmira. “I have been shown beef,” he continued, “which had been issued to my men – that was alive with maggots.” Not satisfied with what he got in camp, the 13th’s Private Duncan found a meal locally. “I paid a woman a quarter for a dinner,” he wrote to his sister back in Newark. “It consisted of dried bacon, cabbage, potatoes, rice, bread, butter and ‘T’: a simple meal, but it seems to me I never enjoyed one so much before.” And though officers fared much better than recruits when it came to food, even Colonel Carman at one point “stopped at a farm house and got a good dinner of bread and milk.”

To add to the poor weather and poor food, it was discovered that the only spring on the southwest side of Maryland Heights where the men were encamped contained an extremely high presence of magnesium. Though magnesium is an essential element for the body, elevated levels can irritate the bowels and cause extreme diarrhea. After drinking it, thousands on the Heights became sick by the time the spring was abandoned as a source of water. From then on the men had to traipse down to the Potomac River, making it very labor intensive to bring water up to the camp on a daily basis. Said one soldier camped there: “We have a great job to get water; have to go a mile down and then three can get only enough for coffee.”

The plateau itself on Maryland Heights was also inadequate as a camp site. Its location facing west gave the men limited exposure to the sun. But the camp itself, located on land of local farmer John Unseld, was just too small to house the thousands of men assigned there. To make matters worse, the shallow, rocky soil on the Heights made the digging of proper latrines almost impossible, especially at a time when so many were initially sickened by the water. These things combined would introduce a new enemy that neither regiment was prepared to fight. As one New Yorker put it, that time for the regiment was “the darkest in its history, when disease and death was everywhere in the camp.”

Hundreds of men in both regiments would end up hospitalized, but the ultimate impact of disease would be much different between the two regiments. Though the 107th and 13th had approximately the same number of men, were camped in the same place, experienced the same weather, ate the same food, and drank the same water, deaths from disease among the New York troops that began with Corporal Couse would far surpass deaths among the Jerseymen that began with Private Demarest.

The second part of this article will examine the impact disease had on the two regiments and the reasons why it was deadlier in the 107th New York than the 13th New Jersey.

Does anyone know what “brain fever” might be in more modern terms? That was also the cause of death listed for my great-great-great-uncle who died in February 1863 while serving with the 3rd Mississippi Battalion in Tullahoma, Tennessee. He too left behind a very young, pregnant widow in New Orleans (who married his brother after the War).

In my analysis, most of the causes of death had an identifiable disease such as typhoid, pneumonia, consumption, etc. But there were some who also died of “brain fever”, “camp fever”, “intermittent fever”, and “congestion of the brain.” In my brief research on these terms, they could be referring to encephalitis or meningitis. Or perhaps the cause of death was unknown and these are more of catch-all terms.

Those two possibilities occurred to me, too. It was said of my uncle that he expired so quickly once the symptoms came on, that after his tentmates lifted him up to carry him to the camp hospital, he died before they could get him there. However, he had been suffering from sickness on prior occasions according to a letter home from a fellow soldier, to the point that he attempted to hire a substitute but was refused.