Killed in Action

Today marks the 150th Anniversary of the death of Union Major General John Sedgwick, the victim of a Confederate sharpshooter. At the time “Uncle John” commanded the VI Corps. By date of rank he was the senior U.S. casualty of the Civil War, although an army commander (Major General James B. McPherson) would die July 22 before Atlanta.

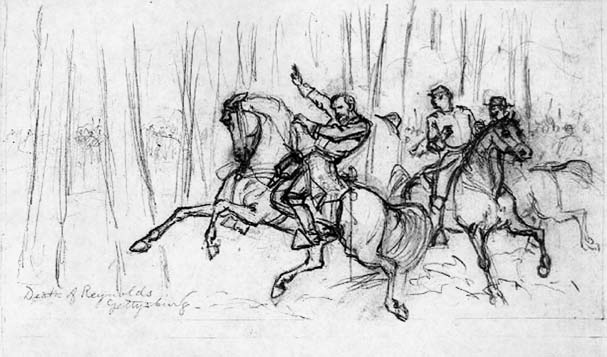

Four Union corps commanders were killed in battle during the war, representing four of the 25+ Union corps created 1862-1865. All four died with the Army of the Potomac – Major General Jesse L. Reno of IX Corps at South Mountain (14 Sept 1862), Major General J.K.F. Mansfield of XII Corps at Antietam (17 Sept 1862), Major General John F. Reynolds of I Corps at Gettysburg, and Sedgwick. Adding in wounded corps commanders, the Army of the Potomac again leads the pack by a good margin. This is an interesting coincidence, and prompts the question: Why was corps command so unhealthy in the Army of the Potomac compared to elsewhere? Below are some answers.

– SIZE AND SCOPE. For virtually the entirety of its existence, the Army of the Potomac was the largest army ever fielded by the United States up to that time. Moving and fighting occurred on a scale larger than any other United States army in the war. Indeed, many other Union armies were the size of corps in the Army of the Potomac. Tactically, this bulk meant the basic unit of maneuver on the Eastern battlefield was the division, versus a brigade in the West – which placed the major direction and decisionmaking on the corps commanders in the East and the division commanders in the West. Western corps commanders in battle tended to be “traffic cops” versus their Eastern comrades, who played a more direct role in executing tactical operations – contrast George Thomas of XIV Corps at Chickamauga versus Winfield S. Hancock (who was wounded) at Gettysburg. The compact size of the Virginia theater also kept corps HQs closer to divisions while in camp; in the West, the corps commander was often at least a day’s ride away from some subordinate camps. All these factors combined to make the corps commander more of a focus tactically and administratively in the East.

– POOR UNDERSTANDING OF ROLES. In addition to the above points, virtually no officers (North or South) had command experience above regimental level in 1861 – most had not commanded larger than a company. In addition to learning how to control large formations, the corps itself was only introduced to the U.S. Army in 1862, at the beginning of the Peninsula Campaign. Tactically, it took some learning as to how corps headquarters fit into the army hierarchy (Alexander McCook at Perryville and Stones River is a good example of the growing pains, and McCook was a former West Point tactics instructor), especially as it was a formation that the commander could not see all at once from one point. This desire to be up front and see led these four all to their deaths.

– COMMAND CULTURE. George McClellan founded the Army of the Potomac with a French-inspired ethos of personal, visible inspiration. This culture produced the reviews, cheering, and emphasis on appearance so often seen in Eastern units as opposed to their Western comrades. However, it also affected leaders, who felt the need to be up front and visibly participating in the battle. All four corps commanders died on the front line, and each were using their personal example to inspire, lead, or steady the troops. A look back at Eastern wounded corps commanders and wounded/dead division commanders shows a similar record and acts of bravado (Hancock and Daniel Sickles at Gettysburg, Philip Kearny at Chantilly, Hooker at Antietam, James Wadsworth in the Wilderness, Horatio Wright at Cedar Creek). Reynolds is a special case, as he was also senior leader on the field; arguably, he had no business leading the Iron Brigade into battle and instead should have been in Gettysburg seeing the big picture.

A final point proves the rule: McPherson’s death in July at the head of the Army of the Tennessee. Unlike the four in the East, General McPherson was not on the front line; he died in the rear while riding from one side of his army to the other, trying to coordinate a defense but leaving his subordinates to lead the fight. As he did this, Confederates who had broken through killed him.

For what it’s worth, date of rank is the only important thing when it comes to rank. The nature of the command is not a factor. Sedgwick was the highest ranking Union officer killed in action during the Civil War. Period.

I think this is a really good writeup but I’d like to argue a point of semantics in the conclusion. James McPherson was not in the rear of his army; he was on the left flank. The Army of the Tennessee was positioned in a formation that somewhat resembled a U. When Hardee attacked, Cleburne’s division broke through a gap between the 17th and 16th Corps at the bottom of the U McPherson was riding into the gap when he was killed. Again, just semantics.

Great write up.

Thank you for these posts, since middle school I’ve been very interested in Civil War and Reconstruction Era America, and I always enjoy reading.