“These poor girls died stainlessly in the midst of youth and beauty”: The Washington Arsenal Explosion

We are pleased today to welcome back guest author Ryan Quint.

In the midst of the 150th Anniversaries of the Overland Campaign, the road to Atlanta, and the opening shots of Petersburg, it is easy to overlook other events that occurred during the summer of 1864. One of these events is the June 17, 1864 explosion at the Washington Arsenal in the District of Columbia.

The Arsenal was located along the banks of the Potomac River where everyday workers produced a wide variety of material needed for the Union war effort. On average, the employees at the Arsenal could create, box, and ship out 21,000 rifle cartridges a day. Young children, employed for their small hands, varnished 7,000 percussion caps an hour.

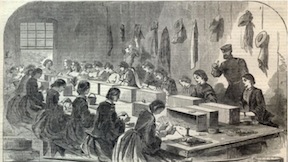

In the middle of the Arsenal grounds was the laboratory, where a corps of 110 women labored in 12-hour shifts, producing the bullets that would soon be sent to Petersburg and other battlefields. These women ranged in age and social status, but most fell into their early twenties and had been hired because of the economic need. Sally McElfresh was likely the youngest girl at the laboratory; she was 12 years old.

The women worked at long tables inside the laboratory, sitting next to each other on hardened benches. Wearing bulky dresses, it was nearly impossible to quickly get up from the benches; if a woman in the middle of the bench wanted to get up, the whole row had to slide off the end and allow her exit. This time-consuming process would have deadly ramifications on June 17.

Within the walls of the laboratory, the women worked mostly at “choking” cartridges. This entailed taking paper cartridges that had already been partially filled with black powder and inserting the rifle bullet, then tying, or ‘choking’ the whole round with some thread. The choked cartridges were then loaded into boxes of 1,000 each. The end result, while filling boxes quickly, also left loose powder lying about the tables and floor of the laboratory.

Early in the morning of June 17, the Washington Arsenal pyrotechnist, a man named Thomas Brown, began to produce fireworks for the upcoming Independence Day activities in the nation’s capital. Brown created hundreds of stars, a type of firework made up of wet clay packed tight with black powder and other explosives. Laying the stars out on large sheets, Brown put the sheets behind a large pile of timber so that they could dry throughout the day.

June 17 was a hot day in Washington: by 7 a.m. it was 72 degrees, and by 2 p.m. the mercury was recording a temperature around 92 degrees. But by 2 o’clock, disaster had already struck at the Arsenal. The sun’s rays did more than dry Thomas Brown’s stars—they cooked them. Behind the pile of timber, no one noticed when the fireworks began to smoke and fizzle. Then, around noontime, they exploded.

Nearby, the laboratory’s windows had been thrown open to allow any type of breeze into the stuffy confines near the benches. But when the fireworks exploded, the flames sped alongside the wind and the fire leapt through the open windows. Sparks and flames lapped at the benches, and before anyone could do anything about it, the loose powder and choked cartridges became engulfed in a massive fireball.

Women, trapped at their workbenches, were soon enveloped in the flames, and many died instantly, the oxygen burned from their lungs. Others managed to make it out of the building, but were still victims of the fire, with the Washington Evening Star reporting later, “One young lady ran out of the building with her dress all in flames, and was at once seized by a gentleman, who, in order to save her, plunged her into the river.”

If the workers managed to escape the confines of their stations, their clothes also acted as conduits for the fire. Their big burly dresses became fully immersed with flames, with the horrifying result, “of the sad spectacle… presented by a number of the bodies nearly burned to a cinder being caged, as it were, in the wire of their hooped skirts.”

The large explosion and ensuing pall of smoke drove many to the Arsenal grounds, but there was little they could do. By the time that many arrived, all they could do was help extinguish the flames and then begin the work of retrieving the dead. Making their way through the debris of the explosion, many of the recovery teams were forced to, “place boards under each one in order to remove them from the ruins,” because of the condition of the corpses. The dead were placed under large canvas tarps with the hope that they could be later identified. Many weren’t; Johanna Connor’s remains were only identified by a piece of her dress that had been burned onto her body.

When all was said and done, the Washington Arsenal explosion killed twenty-one women, including the 12-year-old Sally McElfresh. Washington had seen its share of death and suffering throughout the war, but this was different. The women killed were not soldiers on a battlefield in Virginia, or Georgia. They were not supposed to die. The Daily Morning Chronicle eulogized the victims, “These poor girls died stainlessly, in the midst of youth and beauty; died in their efforts to maintain themselves and parent; died with the June flowers perfuming the air…”

On June 19, two days after the explosion, most of the victims were buried in a funeral that Noah Brooks, a close friend to President Lincoln, described as a, “remarkable and imposing funeral pageant… it is estimated that over 25,000 persons were present.”

Remarkably, Thomas Brown, the man behind the explosion, faced no repercussions for the deaths. He did not even lose his job at the Arsenal, leaving Noah Brooks to write, “Gross carelessness…. Was the cause of hurrying to a premature grave this band of young, lovely, and estimable women.”

————

For those interested in reading more into Washington Arsenal Explosion, truly an underappreciated event during the capital’s Civil War history, I highly recommend Brian Bergin’s The Washington Arsenal Explosion: Civil War Disaster in the Capital,” published posthumously by the History Press in 2012. Most of my notes come from Bergin’s excellent book.

————

Ryan Quint was born and grew up in Maine, and fostered an interest in the Civil War since very early in grade school. After he graduated high school, Ryan chose the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg because of its proximity to the battlefields and National Park Service. He has been a volunteer at Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania NMP for more than a year, and this fall will be heading into his senor year as an undergraduate.

Good Article. It seems what one can learn about the civil war is infinite