Walking the Exposed Federal Line at Reams Station

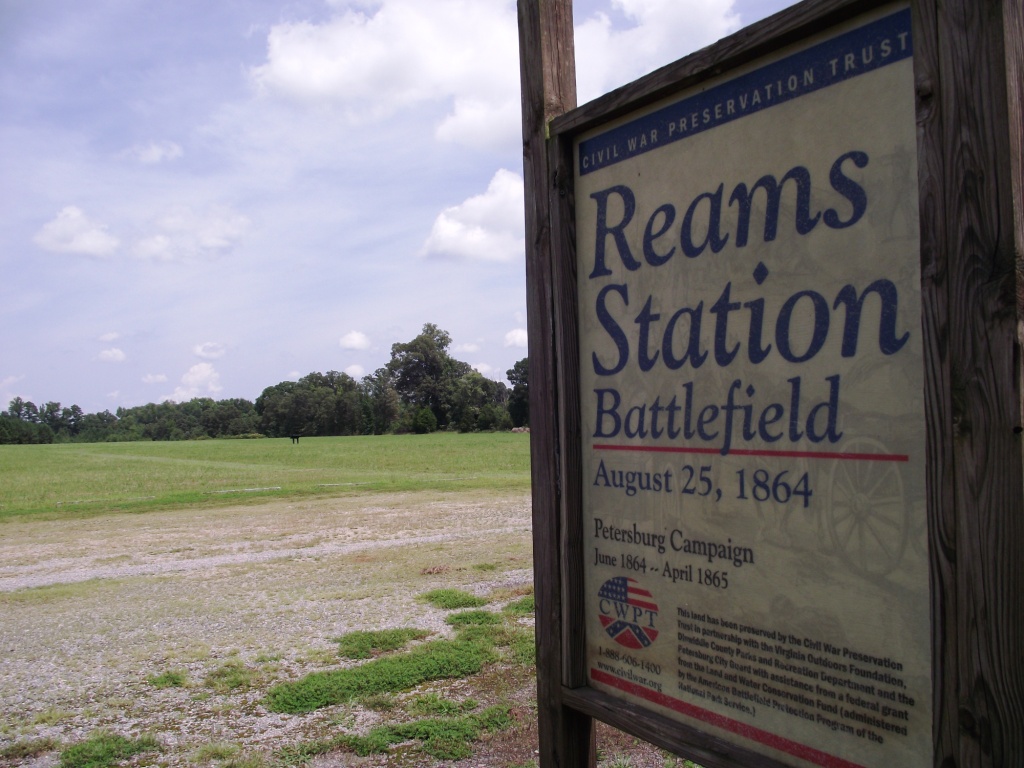

Key to the Union failure at Reams Station is the poor tactical position they assumed around the tracks of the Weldon Railroad. This morning’s piece by Ryan Quint explores the previous exhaustive campaigning experienced by the Second Corps of the Union Army of the Potomac and its impact on their fighting quality at this battle. A brief mental lapse doomed their chances and cost the corps dearly, as a visit to the Civil War Trust preserved section of the battlefield demonstrates.

Key to the Union failure at Reams Station is the poor tactical position they assumed around the tracks of the Weldon Railroad. This morning’s piece by Ryan Quint explores the previous exhaustive campaigning experienced by the Second Corps of the Union Army of the Potomac and its impact on their fighting quality at this battle. A brief mental lapse doomed their chances and cost the corps dearly, as a visit to the Civil War Trust preserved section of the battlefield demonstrates.

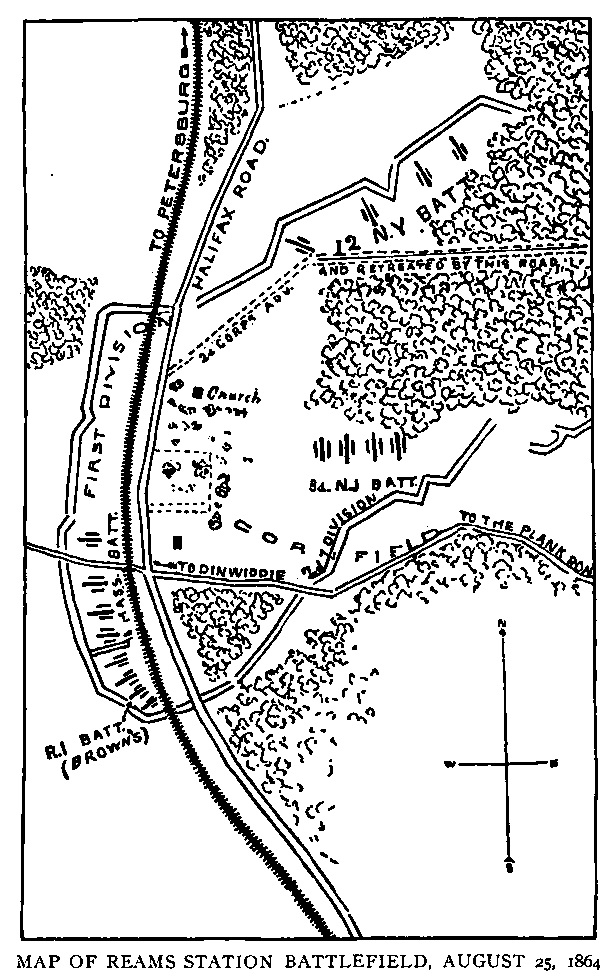

The Second Corps position at Reams Station incorporated earthworks dug by the Sixth Corps in late June while scrambling to the railroad to protect the returning cavalry of the Wilson-Kautz Raid. “They were hurriedly thrown up, badly constructed, and poorly located,” critiqued Lieutenant George K. Dauchy who commanded the 12th Battery, New York Light Artillery.[1] Nevertheless the Second Corps artillerists manhandled their pieces into this position, rather than building a new one from scratch.

Bay Stater John D. Billings of Sleeper’s battery complained about the earthworks supposed to protect his artillery: “That part of the line west of the railroad was a mere rifle-pit not more than three feet in height, and of frail structure, being built of fence-rails within, and these were slightly banked with sods and loose earth. Behind this part of the line we were ordered to place our four pieces.”[2] This small line required expansion to cover the entire Second Corps, and they soon adopted a U-shape position. Those forced to build fresh earthworks made quick haste in creating a firing platform. “As soon as the pieces were placed in position the cannoneers were set to work,” remembered Sergeant John H. Rhodes, of Battery B, First Rhode Island Light Artillery, “and by sunrise had thrown up around the pieces substantial works.”[3] But those who inherited their earthworks took fewer precautions, and focused on relaxation after a strenuous journey that began east of Richmond:

Having taken the position assigned us, there was nothing to do but enjoy ourselves as we chose, for fatigue duty did not usually pertain to the lot of light artillerymen. A cornfield not far off furnished us a liberal quantity of roasting ears during the day, and some good early apples were brought into camp by the more enterprising foragers. We remember the day as an extremely pleasant one, both in respect of the weather and our enjoyment of the surroundings. It seemed very holiday-like to us as we lounged about the guns.[4]

The bedraggled corps should have been making necessary improvements all around their exposed position. “The ground immediately in front of the battery was comparatively clear of large timber, though covered with brush sufficiently high in many places to conceal the movement of the troops,” remembered the diligent Rhode Island sergeant. “To the right and front (northwest) were heavy timber, in which the enemy’s infantry was massed.”[5] But few held belief that the Confederates would contest the expedition along the railroad. “So little expectation had we formed of any severe fighting on this part of the line, that we had not only had not adopted our usual precaution of strengthening our position, but had loaned every pick and spade to a regiment requesting their use, and did nothing whatever to improve our frail breastwork,” claimed Billings.[6]

As Confederate infantry of the Third Corps and Hampton’s cavalry descended on the operation to cut the Weldon Railroad, Hancock’s troops pulled back into their horseshoe position. John Gibbon, whose infantry division formed the section of the line facing south, quickly condemned the earthworks: “Hasty examination disclosed the fact that the line was very unfortunately placed for defense.”[7] Another New York infantryman expressed great frustration at the poor quality of the earthworks around Reams Station, especially after witnessing imposing fortifications in places along the Overland Campaign and around Petersburg: “I had the idea that they were old and poor works; certainly they did not withstand shelling as well-made earthworks would have done. At Cold Harbor we poured a ton of hot iron on their works before the assault, and it did small damage.”[8]

The earthworks did not hold up against repetitively stubborn Confederate assaults, the normally staunch defenders too exhausted and their newly recruited comrades too inexperienced to put up much resistance. With many of its best members lying somewhere between the Rapidan and the James, the Second Corps was not its former self, as described in this morning’s piece. A quick respite on the railroad turned into a frantic struggle to escape. By nightfall nine Second Corps artillery pieces, including several that previously repelled Pickett’s Charge, now lay in enemy hands.

[1] Dauchy, George K. “The Battle of Ream’s Station.” Military Essays and Recollections: Papers Read Before the Commandery of the State of Illinois, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, Volume 3. Chicago: The Dial Press, 1899, 129-130.

[2] Billings, John D. The History of the Tenth Massachusetts Battery of Light Artillery in the War of the Rebellion, 1862-1865. Boston: The Arakelyan Press, 1909, 311.

[3] Rhodes, John H. The History of Battery B, First Regiment Rhode Island Light Artillery, in the War to Preserve the Union 1861-1865. Providence: Snow & Farnham, Printers, 1894, 326.

[4] Billings, 311-312.

[5] Rhodes, 327-328.

[6] Billings, 312.

[7] Gibbon, John. Personal Recollections of the Civil War. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1928, 256.

[8] Estherville Daily News, February 7, 1890.

My ancestors were the Reams here as Confederates and I had family from NY here too, Both from my mother’s side of the family..