“The Very Essence of Nightmare”—The Battle of Plymouth, NC, and the Destruction of the CSS Albemarle

We are pleased today to welcome guest author Sam Smith

part one in a series

The Civil War forever changed Plymouth, North Carolina. The city, like so many others, suffered for its strategic significance. Plymouth controlled the Albemarle Sound and the final stretch of the Roanoke River, making its capture an early priority as the Union fought to establish its blockade of Southern waters. The city was burned twice, once by each side, before being firmly held by Union forces starting in 1862.

The Plymouth of 1864 “was a mere remnant….a few tumble-down houses that had escaped the flames, two or three brick stores and houses, and the rest a medley of negro shanties,” observed Massachusetts Sergeant Warren Goss, who arrived in February. “The place was a general refuge for fugitive negroes…and for rebel deserters.” Two women came down from Massachussets and “schools had been established for the young and middle aged colored population.” [i] Altogether, roughly 2,000 civilians, mostly fugitive slaves, were clustered along the southern bank of the Roanoke River. They were known as “the Plymouth Pilgrims.”[ii]

“Rude frame buildings” were used to shelter the 2,784 soldiers of the Union garrison. The soldiers spent most of their time building a chain of five wooden forts, connected by rifle pits, forming a protective arc around the southern approaches to the village. They also attended church services, swapped gifts from home, and gossiped with Confederate deserters. “We began to feel that we had got a pretty soft thing,” remembered New York Sergeant Nathan Lamphere.[iii]

Soldiers and refugees sometimes cooperated on reconnaissance missions that brought in supplies and slaves from surrounding plantations. Pennsylvania Captain J.B. Kirk later recalled one such incident:

About five or six girls, of say, 18 or 25, led the van, shouting as they came over: ‘Oh! It’s Joe; it’s Joe! And, bress de good Lawd, de Yankees is come at last.’ So without more ado, one of the girls charged on Joe in front, another behind, some more on the sides, and altogether they were too much for him, and as it had been raining recently and the ground was somewhat slippery, Joe’s feet slipped and, the girls holding on, the entire outfit slid down the bank, some six or eight feet, mixed up in an indescribable mass.…

When they got untangled and came up we crossed over to the main body, and their different ways of expressing their joy would be hard to forget….Thus the night passed and 150 slaves passed from bondage to liberty.[iv]

As winter became spring, Confederate scouts began to probe the outskirts of the ramshackle village. More fugitives came in from the countryside, bringing rumors of a Confederate ironclad being built upstream. “It got to be an old story and not generally believed by the rank and file at least,” remembered Sergeant Lamphere. In late 1862, gunboats had swept the Roanoke, destroying anything that looked remotely like a shipyard. An ironclad could not just appear out of thin air.[v]

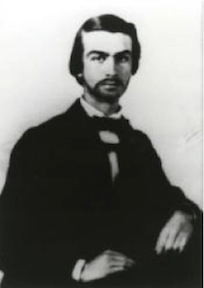

Nineteen-year old North Carolinian Gilbert Elliot was painfully aware of this fact. When he reported to the “Edwards Ferry Shipyard,” in early 1863, he found it to be nothing more than a cornfield. There were no shipbuilding facilities and no raw materials, but Elliot was contracted to build an ironclad ram strong enough to challenge the Union flotilla at Plymouth. From day one, he had to scavenge and innovate to build his war machine.[vi]

A skeleton group of soldiers and engineers were under Elliot’s command. He tasked many of them with scouring the countryside for any kind of smeltable metal. In some cases, citizens opened their pantries and storerooms to the soldiers, giving over pots, pans, and tableware to strengthen the ironclad’s armor.[vii]

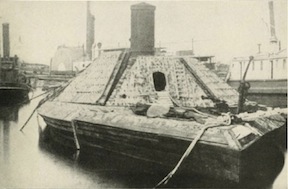

Other men went into the surrounding woods, chopping rails to fashion the ironclad’s wooden frame. For his part, Elliot managed to secure a shipment of smeltable railroad ties and taught a new drilling technique which allowed his engineers to put holes through metal with unprecedented speed. From January 1863 to April 1864, what began as a logistical pipe dream became the ironclad ram CSS Albemarle. The engineers affectionately referred to her as “the Cornfield Ironclad.”[viii]

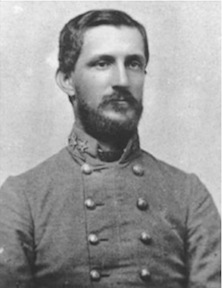

Elliot’s improbable machine was not meant to subdue Plymouth by itself. The April offensive would be a joint operation supported by 10,000 infantrymen under the command of Robert F. Hoke, “Lee’s Modest Warrior.”

Robert Hoke was 25 years old. He had joined the army in 1861 as a second lieutenant and had risen to brigadier general for gallantry on battlefields such as Big Bethel, Second Manassas, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. In the spring of 1864, he and his men were part of a broad Southern counter-offensive meant to threaten potential amphibious landing points along the Atlantic seaboard. With Union armies poised to advance overland towards Richmond and Atlanta, Confederate high command did not want to face a third, seaborne, column. By Sunday, April 17, Hoke’s vanguard was at the outskirts of Plymouth. When the “Pilgrims” left church, they were greeted by panting cavalry pickets describing the approach of thousands of Rebels.[ix]

As the gunfire grew louder from the rifle pits on the edge of town, Union propagandists circulated through the refugee population of Plymouth. The Confederates will kill you, they said, they will kill any and all for the crime of being black and free. The refugees believed the rumors. The events of the next few days would, after all, prove them true.[x]

————

Sam Smith is the Education Manager for the Civil War Trust. A native of Nashville, Tennessee and a graduate of the University of North Carolina, Sam’s educational background embraces American history, pedagogy, and experimental theater. After working in Chapel Hill public schools, he is now focused on exploring new methods of learning history through active participation, decision making, role playing, and simulation. He oversees the manifold K-12 educational programs provided by the Civil War Trust. An award-winning board game designer, Sam has also written or co-written more than thirty articles on Civil War subjects and is a frequent lecturer at the National Museum of American Jewish Military History.

————

[i] Goss, Warren L. “The Soldier’s Story of his Captivity at Andersonville, Bell Isle and other Rebel Prisons.” Civil War Plymouth Pilgrims Descendant Society, 2014. Web. 29 July 2014.

[ii] Urwin, Gregory J. W. Black Flag over Dixie: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in the Civil War. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2004. Print.

[iii] Lamphere, Nathan. “The Fall of Plymouth” Civil War Plymouth Pilgrims Descendant Society, 2014. Web. 29 July 2014.

[iv] Kirk, James B. “From Bondage to Liberty.” 101st Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry. N.p., 2014. Web. 29 July 2014.

[v] Lamphere, Nathan. “The Fall of Plymouth” Civil War Plymouth Pilgrims Descendant Society, 2014. Web. 29 July 2014.

[vi] Blair, Dan. “Albemarle, CSS.” NCpedia. N.p., 2006. Web. 29 July 2014.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Billingsley, A. S. From the Flag to the Cross: Or, Scenes and Incidents of Christianity in the War ; the Conversions … Sufferings and Deaths of Our Soldiers, on the Battle-field, in Hospital, Camp and Prison ; and a Description of Distinguished Christian Men and Their Labors. Philadelphia: New-World Pub., 1872. Print.

[x] Urwin, Gregory J. W. Black Flag over Dixie: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in the Civil War. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2004. Print.