Demonstration at Decatur

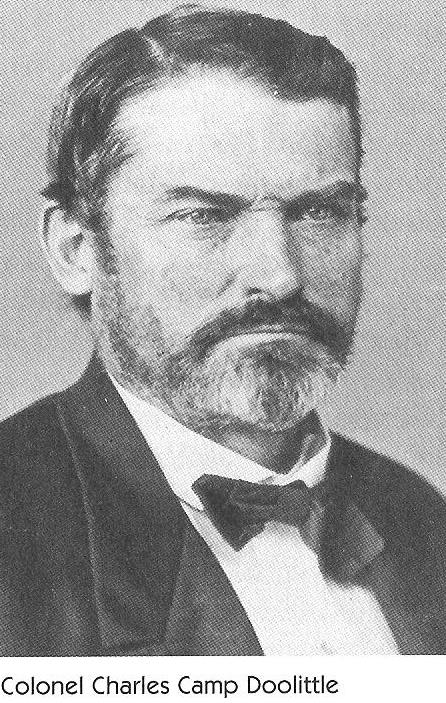

At 1:30 in the afternoon of October 26th, 1864, Union Colonel Charles C. Doolittle of the 18th Michigan Infantry, the Federal commander of the defenses at Decatur Alabama, observed an alarming sight. Several thousand Confederate soldiers were marching up the Somerville Road and deploying to face his defenses.

At 1:30 in the afternoon of October 26th, 1864, Union Colonel Charles C. Doolittle of the 18th Michigan Infantry, the Federal commander of the defenses at Decatur Alabama, observed an alarming sight. Several thousand Confederate soldiers were marching up the Somerville Road and deploying to face his defenses.

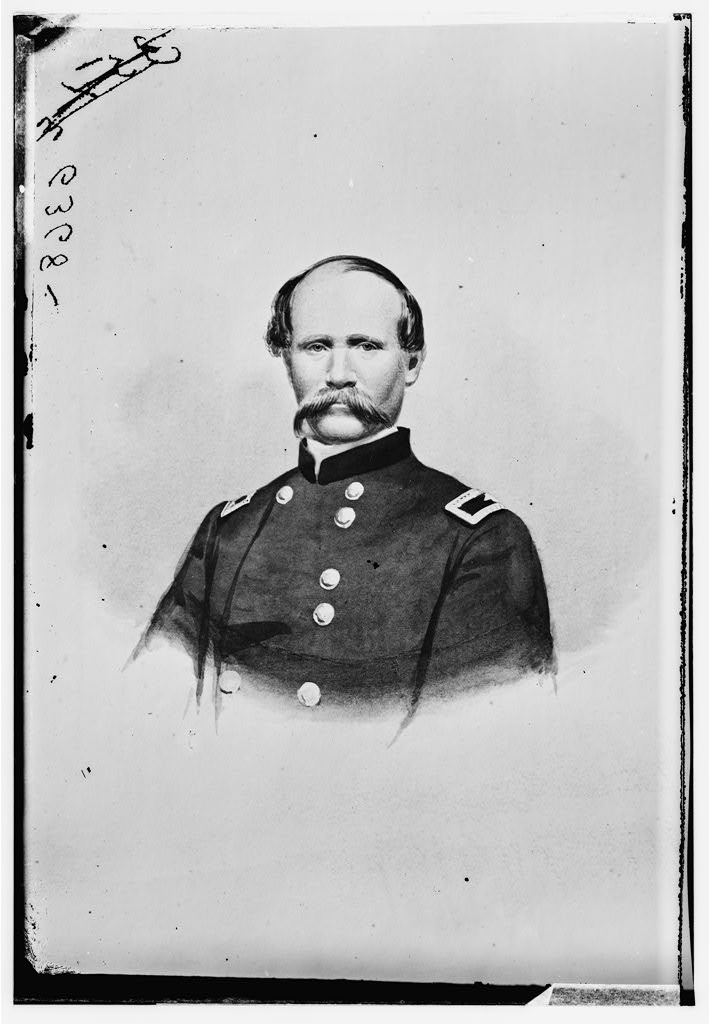

Their appearance was not unexpected. Doolittle’s 1,800 man garrison was part of Brigadier General Robert S. Granger’s District of Northern Alabama, tasked with defending the line of the Tennessee River and with protecting Sherman’s supply lines. Since the capture of Atlanta, Confederate General John Bell Hood had been trying to savage those same supply lines in hopes of drawing Sherman back north. Having met with only limited success in North Georgia, Hood now conceived of a more ambitious goal: slip across the Tennessee in Alabama and strike towards Nashville Tennessee. Taking Nashville would do immense damage to Sherman’s logistics, and almost certainly draw the Federals out of Georgia.

On October 22, Hood cut loose from his base at Gadsden, aiming to cross the river somewhere between Guntersville and Florence. His new supply line, such as it was, would run through Tuscumbia Alabama, across the river from Florence, where it would be safe from interruption by Union gunboats due to the proximity of Muscle Shoals. Four days later, he was nearing Decatur.

The Federals were aware of the danger. Granger’s troops were put on alert, and both river and road patrols were beefed up. On the morning of the 26th, one of such patrol encountered Rebels from A. P. Stewart’s Corps, The Army of Tennessee, headed northwest out of Somerville, and alerted Doolittle to the threat.

Hood’s army might have been much reduced after the bloodlettings around Atlanta, but the Confederate force still numbered 35,000 men – more than a match for Doolittle’s outpost of a command.

And yet, for the next four days, the Federals at Decatur would stare down Hood’s army. The Union defenses here were well sited, a 1,600 yard semi-circle of earthworks that ran from river-bank to river-bank, forming what amounted to a fortified hedgehog. Decatur itself was largely deserted, most of the buildings having been dismantled to use in building these defenses. Three batteries of artillery, 18 guns, covered the approaches, across a largely level plain some 800 to 1000 yards wide.

Doolittle was reinforced, but only slightly. General Granger arrived from Huntsville on the evening of the 26th, bringing with him a few detachments. A few more would arrive over the next day or so, but the Union defenders would never rise much above 4,500 effectives. By contrast, Hood’s entire army was present by the 27th, to commence what appeared to be preparations for assault.

Hood soon discovered that Decatur was too tough a nut to crack easily. When Confederate sharpshooters from Walthall’s Division established a rifle pits just 500 yards from the Union trenches, a daring Federal sortie scattered those Rebels, capturing more than a hundred, all at a cost of two wounded Yanks. When Stewart’s artillery attempted to establish batteries close enough to batter down those defenses, Granger’s cannon punished them with accurate, effective crossfire, and drove the Rebel gunners back to shelter.

In the end, the Army of Tennessee never made a serious effort to storm the defenses. Hood would hater dismiss the whole thing as merely “a slight demonstration,” a pause on his march to Tuscumbia. It’s likely that Hood and his generals never realized how few defenders were actually present, and believed the works to be more strongly held than they actually were.

For the Yankees, it was proof again that nerve and resolve could win out even against hopelessly long odds; if the defenders were well-prepared and strongly entrenched. Union losses amounted to 113 men. Confederate casualties went unreported, but likely amounted to at least a couple of hundred, maybe as many as half a thousand. The Federals took a reported 139 prisoners during the fight.

The costs of Decatur reach beyond the casualty reports, however. Despite Hood’s dismissal, the delay at Decatur cost the Confederates an early chance to cross the Tennessee and drive towards Nashville before the Union had time to react. If Decatur were merely to be bypassed, why sit there for four days, all the while with your army’s haversacks empty and food running desperately short? Living off the land in Northern Alabama proved impossible, given that region’s much-ravaged status: Hood’s only choices were to press on to Tuscumbia, where a rail connection to Corinth offered some chance of re-supply, or to cross the River and enter Middle Tennessee, which offered somewhat better pickings.

Hood moved on to Tuscumbia, and waited another three weeks before launching his Tennessee gambit. During those three weeks, Sherman marched seaward and George Thomas gathered troops to defend Nashville. By late-November, Thomas’s army was in much better shape to receive such an attack, as events at Franklin aptly proved. But in late October? Not so much.

Hood tried to emulate Robert E. Lee – move with celerity, strike with ferocity. He wanted to recreate the campaigns of dazzling maneuver and daring strategy that worked in Virginia. But this was 1864, not 1862; the war’s grim circumstances had changed too much for such schemes to work.

Not the least of those changes could be found in Hood’s opponents, who refused to be cowed.

Reblogged this on Practically Historical.

Are any of Decatur’s Union earthworks still visible?

Yes, there are still some things to see in Decatur. They have a bit of a walking tour and some interpretation.