Tenting Among the Dead

Many locations throughout Virginia witnessed multiple battles during the four years of civil war. The slope to Marye’s Heights in Fredericksburg that seemed so insurmountable in December of 1862 again felt the tramp of Union attackers the following spring in a decisively successful charge. The Wilderness of Spotsylvania County muddled tactics and confused soldiers during early May of both 1863 and 1864. Union and Confederate armies vied for the Cold Harbor crossroads near Gaines’ Mill at the end of McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign in 1862 and Grant’s Overland Campaign in 1864. Each time the soldiers returned to their previous battlegrounds visual memories of the carnage awaited them. The grueling duration of the Petersburg Campaign guaranteed these grim reminders would be ever present.

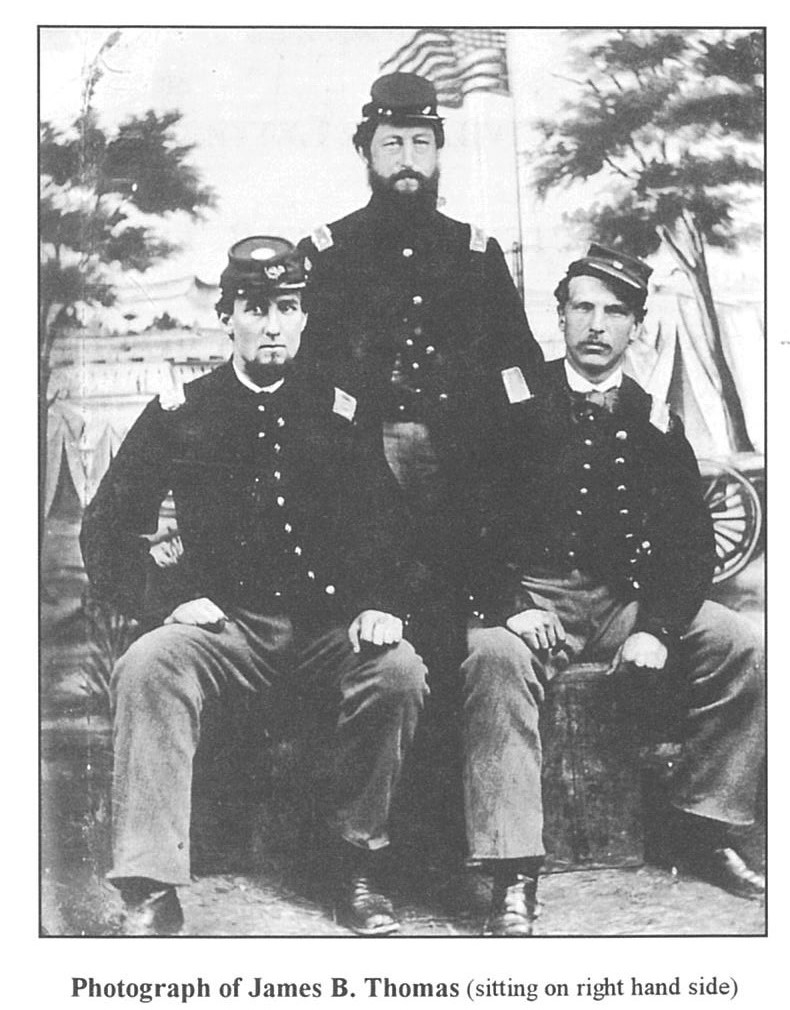

First Lieutenant James B. Thomas and the 107th Pennsylvania Infantry desperately clung to the ground they seized along the Weldon Railroad in August 1864. Union presence astride the tracks cut the major supply line feeding the city of Petersburg from North Carolina. A vicious battle from August 18-21 brought heavy casualties to the northern side but they maintained a strategic victory. The marginally successful Confederates had to yield both battlefield around Globe Tavern and Reams Station and retreated to Petersburg’s inner lines. Meanwhile the Union Fifth Corps hastily improved their new permanent location right atop the previous week’s battlefield. “At this place the dead were all buried where they fell,” wrote Thomas. “There are a great many of them scattered about among the camps.”[1]

First Lieutenant James B. Thomas and the 107th Pennsylvania Infantry desperately clung to the ground they seized along the Weldon Railroad in August 1864. Union presence astride the tracks cut the major supply line feeding the city of Petersburg from North Carolina. A vicious battle from August 18-21 brought heavy casualties to the northern side but they maintained a strategic victory. The marginally successful Confederates had to yield both battlefield around Globe Tavern and Reams Station and retreated to Petersburg’s inner lines. Meanwhile the Union Fifth Corps hastily improved their new permanent location right atop the previous week’s battlefield. “At this place the dead were all buried where they fell,” wrote Thomas. “There are a great many of them scattered about among the camps.”[1]

Near the camp of the 107th Pennsylvania, engineers broke ground on Fort Dushane, named for a Maryland colonel slain nearby. Thomas observed the workers finding a burial among the fort’s plotted dimensions: “The engineers, in building the work took great pains with this grave & has made it quite conspicuous, building and bracing up a dirt monument.” Thomas was no stranger to seeing the carnage of battle. During the Cedar Mountain campaign in August 1862 he wrote that Confederate dead stretched along the road for miles: “They were left lay on top of the ground and dirt shoveled over them. Some had their feet sticking out, others their heads, other a shoulder could be seen, then an arm and many were not buried at all, our men performing that rite to about 70 of them.” Shocked by this experience early in his service, he admitted: “I never again want to witness such sights.”[2]

The frequent combat of the Overland Campaign and repeated strikes against the Confederate earthworks and supply lines around Petersburg inured Thomas to death. “I have the head board of one grave inside my tent,” he commented now in 1864. “The nature of the ground was such that I had to encroach upon the grave.” Under the lieutenant’s bed rested the body of Private Alonzo C. Ketchum. The thirty-eight year merchant enlisted at Elmira on October 25, 1861 into Battery B of the First New York Artillery. He stood 5’5” with blue eyes, sandy hair, and a fair complexion.[3] Ketchum observed Christmas Day 1863 by reenlisting into the Union army for another three years. But while servicing his cannon on August 21, 1864, he was struck down and buried on the spot.[4] The need to quickly establish protective earthworks where Ketchum fell took precedence over proper care for the deceased. Lieutenant Thomas, however, took a new view towards the grave that shared company in his tent, proudly considering himself “a sentinel over it.”[5] After the war Ketchum was reburied at Poplar Grove National Cemetery.

Not every soldier hardened to their experiences. “Father if you was out here I could show you some thing that I dunt think you ever did see before,” wrote Emanuel Peter of the 49th Pennsylvania as he arrived into Petersburg in December. “I could show you the bones of soldiers that were killed, and never was buried, and I can tell you it looks pretty hard.”[6] His Sixth Corps spent the previous five months in the Shenandoah Valley, but received a somber reminder of what they could expect in the trenches.

“We got off at Parke Station near Army Head Quarters and right on the battle field of last June,” wrote Aldace Freeman Walker of the 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery. “Sergt. Donnelly of Co. C was buried right by our bivouac.”[7] George Oscar French used his friend Peter Donnelly’s grave to track the Union army’s progress while they were away: “When we left, this spot was two miles in front & beyond our left, now Grant’s left is some six miles to the front. I tell you Grant has done well here.” He was relieved to report: “The grave was all right except we found a railing around it & a better headboard than we had been able to furnish for him.”[8]

Donnelly fared well, but the sheer quantity of casualties and continual reuse of the same space for camp, fort, and battlefield did not allow every soldier a proper burial. As the Sixth Corps continued to improve their adopted positions through the new year they continued to find such harrowing reminders. A member of the 9th New York Heavy Artillery assisting with the repair of Fort Wadsworth found numerous graves, many of them with the bodies near the surface. “The rain washes out the head of a man,” he reported, yet noted the winter quarters located right over top of the graves. “Rather a hard place for nervous and superstitious men!”[9]

Rather a hard place indeed!

[1] Thomas, James B. September 23, 1864 Letter to Father. Mary Warner Thomas and Richard A. Sauers, eds. “I Never Again Want to Witness Such Sights”: The Civil War Letters of First Lieutenant James B. Thomas, Adjutant, 107th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Baltimore, MD: Butternut and Blue, 1995, 249.

[2] Thomas, James B. August 20, 1862 Letter to Lucy. “I Never Again Want to Witness Such Sights,” 75.

[3] Civil War Muster Roll Abstracts of New York State Volunteers, United States Sharpshooters, and United States Colored Troops [ca. 1861-1900]. (microfilm, 1185 rolls). Albany, NY: New York State Archives.

[4] Annual Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New York for the Year 1896. Registers of the First and Second Regiments of New York Artillery, in the War of the Rebellion. Albany, NY: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co., State Printers, 1897, 227.

[5] Thomas, James B. September 23, 1864 Letter to Father. “I Never Again Want to Witness Such Sights,” 249.

[6] Peter, Emanuel. December 28, 1864 Letter to Jacob Peter. Emanuel Peter Papers, Swem Library, College of William and Mary.

[7] Walker, Aldace F. Letter to Father. Tom Ledoux, ed. Quite Ready to be Sent Somewhere: The Civil War Letters of Aldace Freeman Walker. Victoria, BC: Trafford Publishing, 2002, 327.

[8] French, George O. December 154, 1864 Letter to Friends. George Oscar French Letters, Vermont Historical Society.

[9] Roe, Alfred S. The Ninth New York Heavy Artillery. Worcester, MA: Published by the Author, 1899, 214.

This is a wonderful piece, succinct and very informative. It really reveals a new level to the tragedy of how Americans of this era had to come to terms with the prominence of death that the war brought.

Like James Brooks, I read (or at least commented upon) this article on Halloween. I have become increasingly impatient with all the fake “horror” made merchandise of at this season. As you have so ably described our own American battlefields provide all the macabre details most of us are able to take in.

Well done, Edward – What will keep the Civil War real is presenting the participants as they really were. People who lived and loved and bled and died as bearers of the image of God. One of the most awesome and chilling tragedies of all time.