Committees of Correspondence = 18th Century Social Media?

Information. Communication. Solidarity. Linkage. Friendship. Point-of-view. Identity. Current Events.

These words describe reasons in the 20th century why people joined and continue to join social media platforms, especially Facebook.

Approximately 240 years before Facebook was launched in February 2004, the first major attempt at achieving all the proponents above was the job function of the various Committees of Correspondence established in the thirteen American Colonies.

Take a moment to think about it. In the mid-18th century news traveled as fast as horseback from the scene where the event happened. If that occurrence happened across an ocean, the news traveled as quickly as the fastest sailing vessel.

News of the Declaration of Independence which was agreed in full Congress in Philadelphia on July 2, 1776, took a week to reach General George Washington in New York City, was not printed in the Virginia Gazette until July 20th, and was not put in print by the first European newspaper until August 16.

If that same event happened today, how long would it take for Facebook user to make it “trending?”

If news took forever to travel, how did colonists favorable to the independence movement build consensus? Learn about what their fellow patriotic brethren were doing in far-off Massachusetts?

Easy. The various colonies developed Committees of Correspondence.

The idea was unique to the American Revolutionary movement. In fact, the first committee was formed in Boston in 1764 in response to a particular custom regulations passed by Great Britain’s Parliament and deemed oppressive by colonists. The committee decided on a course of action of protest and then disbanded.

New York in the following year, 1765, also formed a committee of correspondence to provide current information on the response to the Stamp Act.

In 1773, Virginia’s House of Burgesses proposed legislation that each colony form a committee for such purposes.

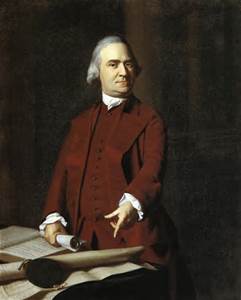

By the eve of the American Revolution it is estimated that between 7,000 and 8,000 colonials favorable to the patriot cause were a part of Committees of Correspondence. Famous patriots such as Samuel Adams and Dr. Joseph Warren were instrumental in the Committee of Correspondence that effectively provided insight, direction, and a modicum of leadership during the tumultuous days of spring 1775.

In fact, it was Samuel Adams, who rose to speak the following words at a Committee of Correspondence meeting on November 20, 1772;

“Among the natural rights of the Colonists are these: First, a right to life; Secondly, to liberty; Thirdly, to property; together with the right to support and defend them in the best manner they can. These are evident branches of, rather than deductions from, the duty of self-preservation, commonly called the first law of nature.”

This informal network, which wrested unofficial control of the colonies from their royal officials and administrators, provided the groundwork that led to the Continental Congresses that convened in Philadelphia.

At the bare minimum, the Committees of Correspondence congealed ideas, thoughts, questions, responses, and motives into a combined effort that eventually matured into a revolution.

How did the committees accomplish this? By effectively spreading,

Information. Communication. Solidarity. Linkage. Friendship. Point-of-view. Identity. Current Events.

Much like social media has done in our world.

Thanks for the post. I often wonder whether the changes in the social media/information age, so called, were as great as those of the period from say 1840 to 1940. Even 100 years after the revolutionary war communications were still as tortoise-like. For the un-wired world of a generation before the transatlantic cable the idea of sending an instant message from America to England was nothing short of miraculous. By way of contrast one only has to compare the death of presidents before and after the cable was at last made to work. It was a whole 12 days before Europe found out that President Lincoln had been assassinated in April 1865. Less than 20 years on, when President Garfield was shot, in September 1881, the British public read about the shooting in their newspapers over next morning’s breakfast.

Thanks Acton Books for the comment and reading the blog post. Great thought there about the jump in technology and communication between 184 and 1940. It will be interesting to compare also the jump from 1915 – 2015 in forms of communication, not just between people, but between government officials, news agencies, and the military.

Thanks again for reading!

Thanks Phil for this thought provoking article. I do wonder if we’ve gained much in this process of speedy transfer of information. In today’s public and social media world there’s a nearly over-whelming volume of information, but too often its content and accuracy are sacrificed in the interest of time. Nearly every day you will see and hear your local tv news remind you that “you heard it here first”, but soon you will learn that omissions and inaccuracies have become obvious and you seldom see and hear follow-up corrections once facts are clear. Back in my working days I remember occasions when I asked my leaders if they wanted a bad result quickly or a quality result a bit later? It’s something to think about and certainly we all need to add a healthy dose of skepticism to what we hear through “news” sources; especially through television and social media. It seems to me they’ve become primarily a source for opinion(s) rather than information.