Melee on the James River

January 1865: the future did not bode well for the Confederacy. President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee watched as their troops dissolved into disarray and confusion, sensing the imminent defeat coming their way. Union General William T. Sherman had burned his way through most of the southern states and Fort Fisher, the only defense point for the crucial Confederate port of Wilmington, was under attack for a second time. Both Lee’s army and the Confederate Navy were in trouble. And they knew it.

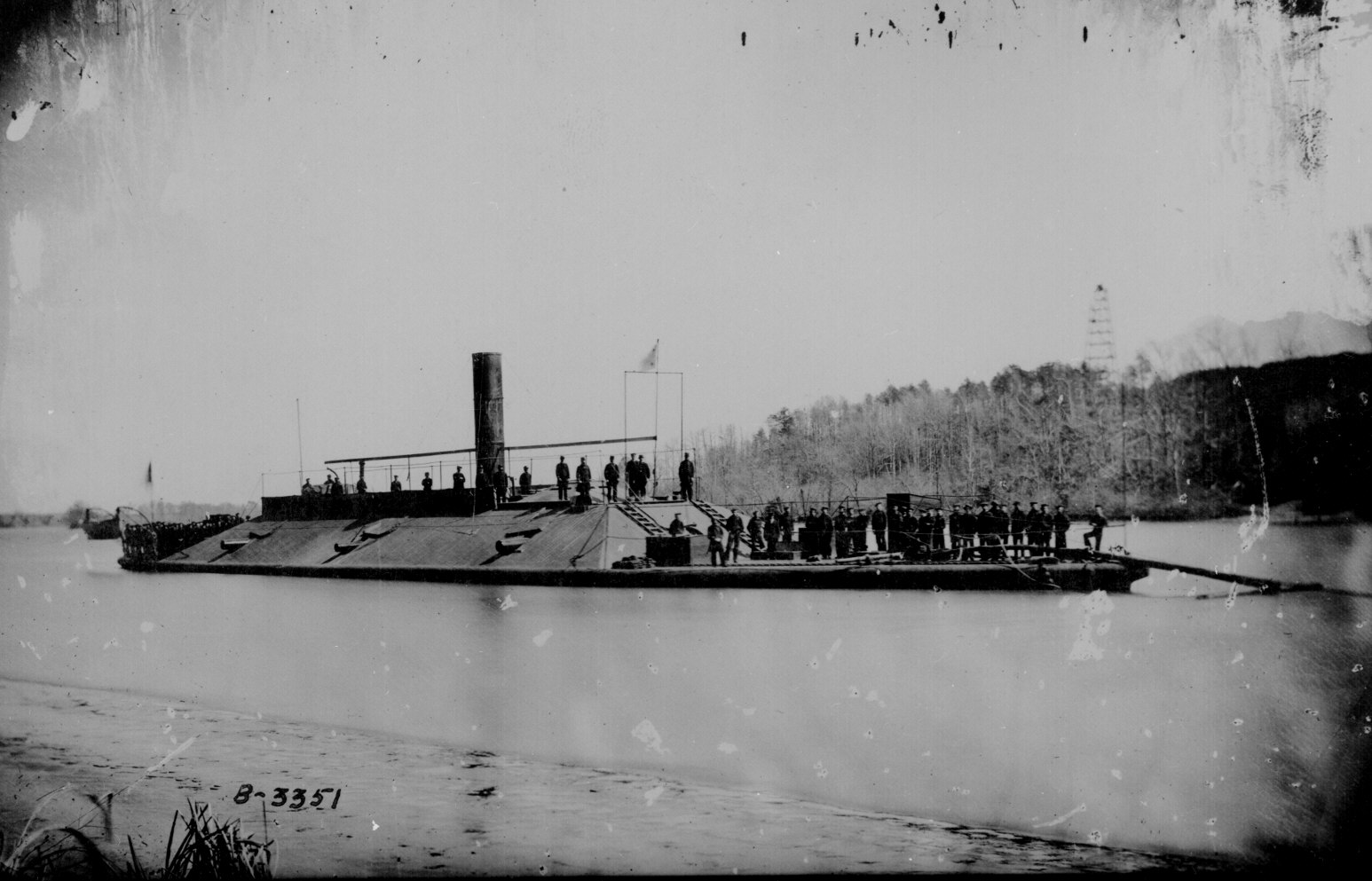

Let’s back up a minute: the James River Squadron was established as a part of that state’s navy shortly after Virginia’s secession from the Union in 1861. Although it began as a modest collection of ships, most of them wooden, the squadron later became a part of the Confederate Navy and participated in the Battle of Drewry’s Bluff on May 15, 1862, a battle during which the ironclad CSS Virginia was damaged beyond repair. After the battle, the ship was replaced by the CSS Virginia II and the squadron was bolstered with the addition of several ironclads. They remained inactive, however, for nearly two years until

May of 1864 when the squadron was sent down the newly-cleared James River.

To their surprise, the James River Squadron encountered several Union barricades blocking the river. The squadron started a conflict that lasted for two months until the grand finale on August 13th when the South opened a full naval bombardment on the Federal Army. The victory was short lived, however, and the James River Squadron continued to pester the northern forces for the remainder of the year from a safe position below Drewry’s Bluff.

After weeks of policing the Union forces along the river, the squadron finally got another opportunity to cause real damage in January 1865. Unusually high waters had caused significant damage to Union barriers. Squadron commander Captain John K. Mitchell

seized this opportunity to attack. The timing was especially opportune because many ships in the Union fleet had recently been transferred to North Carolina to help in the attacks against Fort Fisher. Mitchell and his fleet planned to break through the remaining Union ships and destroy the Union supply line from City Point, a supply base in Petersburg, VA. The ensuing conflict would later be known as the Battle of Trent’s Reach.

As they crept under cover of darkness past the Union batteries on Signal Hill and Fort Brady, Captain Mitchell and his fleet were spotted by Union lookouts. Although they immediately opened fire, the Confederate ships made it through virtually unharmed and continued towards Trent’s Reach, a naval mine field. As the Virginia II and the Richmond anchored above the Federal barriers, the Fredericksburg, another Ironclad, led a smaller fleet to clear the way.

Despite the fact that the Union obstruction had been damaged by high waters, removing it proved to be quite a difficult task. The blockage turned out to be a spar mounted between two hulks. The water level began to recede as the Fredericksburg crew worked to clear the river, sending other boats ahead to prepare the way for the ironclads.

It was a dangerous game the Confederates played, as their position removing the barrier was virtually unshielded from three Federal artillery batteries on shore at Trent’s Reach. Despite the Union riflemen shooting at them throughout the night, the Confederates managed to clear the river by the early morning hours of January 24, 1865, and were ready to move towards City Point.

Obviously by this point in time Mitchell’s fleet had lost any advantage of surprise. The Confederates were met by Union warships poised to attack. Even worse, the ironclads were struggling to maneuver through the now-shallow river. Add to this the disadvantage of the sun dawning as ironclad after ironclad ran aground. The Union batteries relentlessly peppered the grounded ships, including a torpedo boat named Scorpion along with the CSS Richmond, Virginia II, and Drewry.

The North seemed most focused on obliterating the ironclad Richmond, which was still stuck fast against the shoreline. The Drewry’s crew, knowing their wooden ship was doomed, evacuated and struggled desperately to get the Richmond afloat. Managing to board their sister vessel just in time, the Drewry’s crew watched as an enemy shell struck the warship’s magazine, igniting a terrific explosion that claimed the lives of two men still trapped within the burning ship. When it seemed that things couldn’t get worse for the stranded Confederates, they saw two northern ships appear and start to close in.

When it seemed that all was lost, the water level began to rise once again and the Confederate gunboats dislodged themselves from the shallow waters. Both forces retreated. Despite the fact that the James River Squadron was severely weakened, Mitchell regrouped and launched a second attack against Trent’s Reach. It fared no better than the first. They found the Virginia II unmanageable once again, this time due to damages sustained during the first engagement. Mitchell and his commanders met to discuss their available options and decided to abandon the second assault effort. Instead, they moved upriver to a refuge below Chaffin’s Bluff.

Both Captain Mitchell and the Union Commander lost their leadership positions shortly thereafter due to decisions made during the battle on the James River. The Battle of Trent’s Reach would be remembered as the last major naval engagement of the Civil War.

By February 1865, the Union had reinforced navy presence on the James River, successfully preventing any future Confederate offensives. With their failure on the river came the realization that the Confederates had lost the opportunity to break the siege at Petersburg. Many speculate that future events, perhaps even the outcome of the war, would have changed drastically had they succeeded. Nevertheless, the Confederate offensive failed and the Civil War ended three short months later.