A new man in town

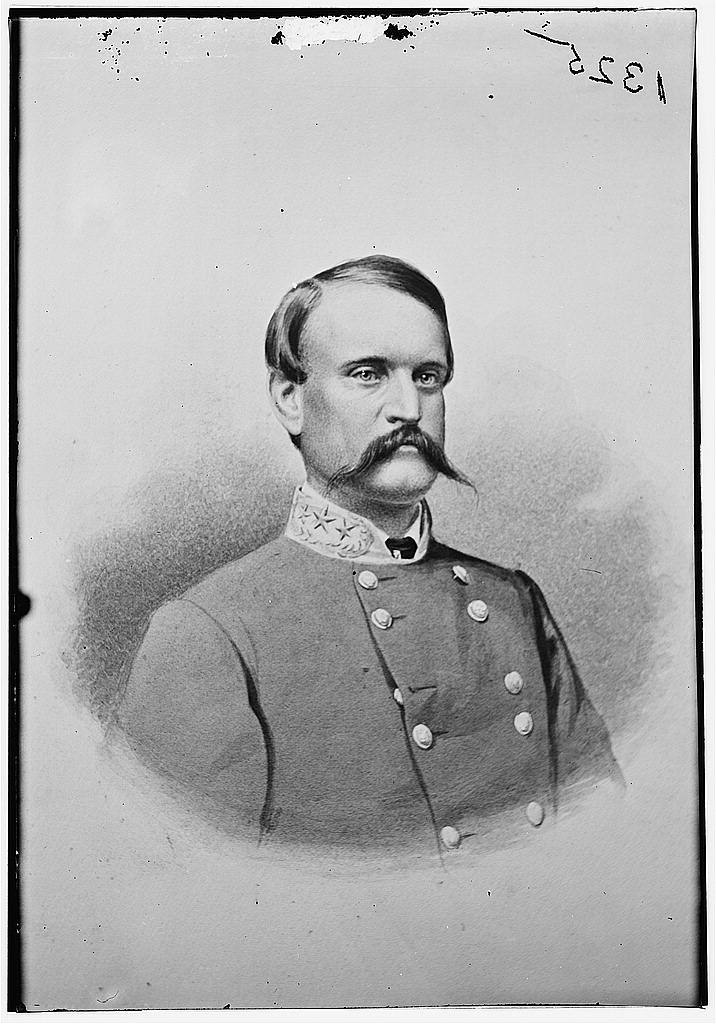

On February 7, 1865, Major General John C. Breckinridge accepted the position of Secretary of War, Confederate States of America—the fifth and final man to hold that job. He assumed the duties of his new office amid desperate times. The Southern Government and the Confederacy’s principle field force—the Army of Northern Virginia under command of Robert E. Lee—were both all but besieged at Richmond and Petersburg by Ulysses S. Grant’s Federals. Elsewhere, Union armies rampaged across the south seemingly at will, as demonstrated by William T. Sherman’s recently completed march across Georgia. Now Sherman was moving northward through the Carolinas.

On February 7, 1865, Major General John C. Breckinridge accepted the position of Secretary of War, Confederate States of America—the fifth and final man to hold that job. He assumed the duties of his new office amid desperate times. The Southern Government and the Confederacy’s principle field force—the Army of Northern Virginia under command of Robert E. Lee—were both all but besieged at Richmond and Petersburg by Ulysses S. Grant’s Federals. Elsewhere, Union armies rampaged across the south seemingly at will, as demonstrated by William T. Sherman’s recently completed march across Georgia. Now Sherman was moving northward through the Carolinas.

Even if not under outright Union occupation, great swaths of the Confederacy were completely disconnected from the central government. Much of Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia were now essentially lawless regions, the locals preyed on by marauders and bandits. Military desertion was rampant; many Confederate soldiers recognized that the war was lost.

Defeatism was not confined to the ranks: On February 8, while conferring with Breckinridge, Assistant Secretary of War John A. Campbell informed his new boss that in Campbell’s view, the war was now “hopeless.” Probably it was. But Breckinridge would see for himself; ordering all department heads to report on the “means and resources” on hand to execute the missions of their particular offices.

Despite the despairing outlook that gripped so many of those around him, Breckinridge did what he could. Among his first acts was to dismiss the incompetent Colonel Lucius B. Northrop, head of the commissary, who had long since been overwhelmed by the duties and nearly insurmountable difficulties of his office. There was little likelihood that at this late stage of the war food for the troops could be either increased or improved, but Breckinridge would at least try.

In fact, the Confederacy had a little more than two months to live. John C. Breckinridge’s biggest challenge would be in orchestrating the wholesale departure of the War Department from Richmond in early April, a desperate affair executed at the last minute when Grant finally severed Lee’s last rail connections and broke through the Rebel lines at Petersburg.

Could Breckinridge have made a difference had he been appointed earlier? In some ways, his appointment was in itself remarkable – representing a surrender of a significant portion of authority on Jefferson Davis’s part. Davis had always run the War Department personally, interfering with and often annoying previous Secretaries. It is an open question if Breckinridge would have lasted longer in the job, or been able to hold his own against the autocratic nature of the Confederate President, but he was both a competent politician and by now a proven soldier, who would not easily let himself be trampled by Davis.

History cannot answer that question. If the fall of Richmond on April 3rd 1865 did not render it moot, the surrenders at Appomattox and Bennett Place certainly did.

All good points. Breckinridge also was instrumental in preserving many of the Confederate war records at the end of the war, when others wanted them destroyed.