Rebels Down Under: Conclusion

Today, we are pleased to welcome back guest author Dwight Hughes.

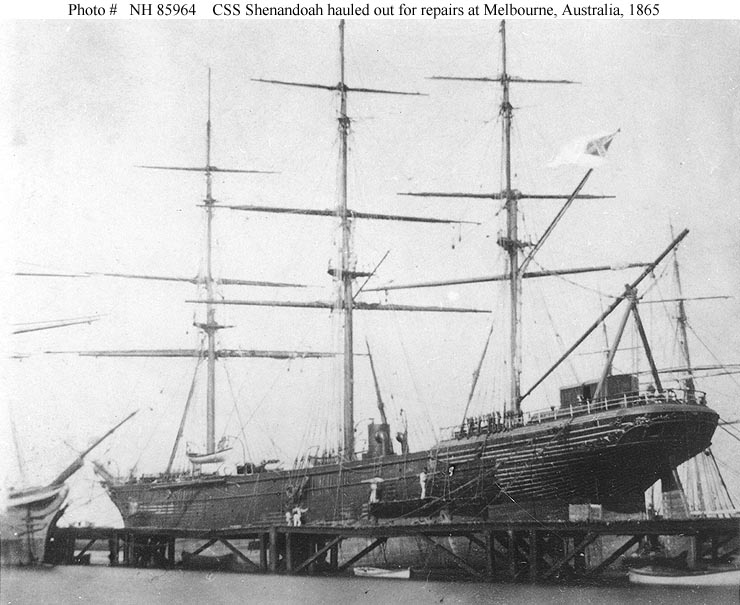

Mr. William Blanchard, United States Consul in Melbourne, desperately applied every legal trick to have Shenandoah seized, all to no avail. As long as they obeyed neutrality rules, Governor Sir Charles Darling had no incentive to act against the visitors, especially with many of his leading citizens in such vocal support of them. Until, that is, Blanchard received information that the Confederates were actively recruiting new crewmen from among the citizenry—a clear violation of the rules of neutrality. The governor acted with uncharacteristic dispatch, impounding the vessel while high and dry on the beach for repairs to the propeller shaft.

A force of policemen armed with loaded carbines surrounded Shenandoah while Royal artillerymen reversed the guns of a nearby battery. Work ceased and workers were ordered out of the yard (although critical repairs to the propeller shaft continued thanks to a prominent sympathizer). The gun raft Elder with two 68-pounders moored nearby ready for action. Intense excitement ensued in the city with rampant rumors of actual or impending violence.

But upon further review, Royal law officers concluded that the governor did not have a good case and could be liable if the vessel were damaged. He was compelled to release Shenandoah to the derision of many citizens and the press.

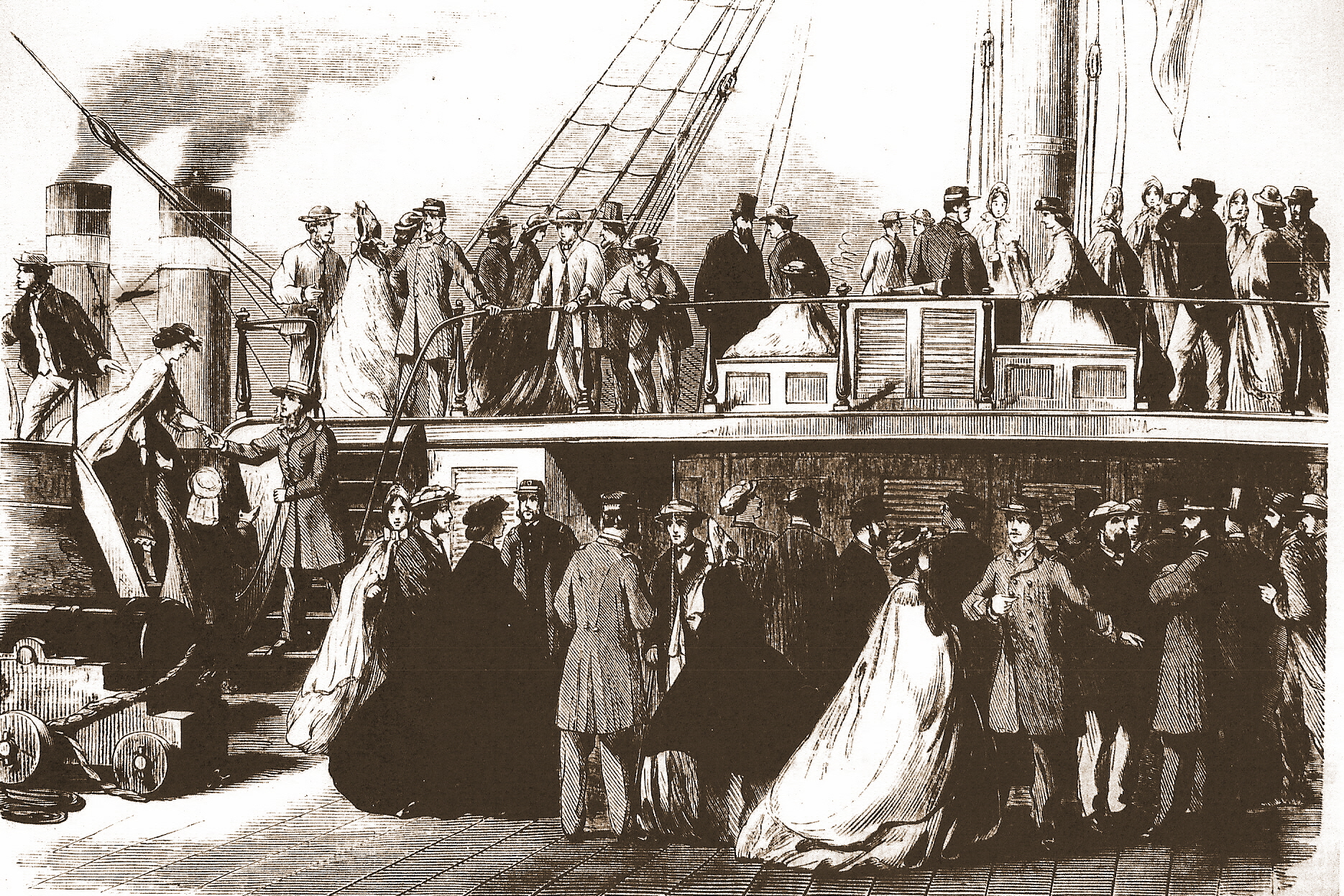

Repairs completed, Shenandoah once more attained her natural element, cheered by a crowd of spectators on adjacent wharves. The colonial steamer-of-war Victoria and other vessels dipped their flags in salute, the last such recognition the Confederate banner would receive. The Age reported that a considerable number of people crossed over the bay in expectation of some sensational scene but the affair passed off without incident.

Meanwhile, the court of public opinion was in session. A large public meeting convened at the luxurious Criterion Hotel, unofficial meeting place for the few thousand U.S. citizens residing in the city. Self-appointed leaders following semi-formal rules of order led a lively exchange. The primary questions was: Had the government acted in accordance with the principles of international law?[i]

One participant, to loud cheers of agreement, maintained that the authorities would never have threatened the ship if she had flown the flag of the Unites States or that of even the most trivial European power. A dissenter responded that they could indeed seize a pirate. But the Shenandoah was not a pirate countered another. The Southerners were of Anglo-Saxon stock, and if they unanimously demanded self-government, they should be allowed. It was an act of cowardice and a breach of hospitality for any government to seize a ship belonging to such a struggling confederation.

Another speaker had been informed that the U.S. consul offered Shenandoah seamen significant bribes to desert and inform against the captain, itself a violation of international law. A barrister-at-law, Mr. Francis Quinlin, maintained that the causes belli was not slavery, but an issue of free trade versus protection; the valor and unanimity with which Southerners acted entitled them to independence de facto and perhaps de jure. Like American colonies in 1775, the Confederacy would prevail.

A resolution was offered that the government had interfered with their happy relations with what was likely to become a great and glorious nation. A Doctor Rowe seconded the motion, noting that Australia should take notice of this struggle as similar to one they themselves could face one day. Another citizen countered that the ship was not Shenandoah, but Sea King; the Southerners had no more right to send out such privateers than those who carried on the Irish rebellion.

A Mr. Herberson protested the public being dragged through the dirt and made subjects of ridicule for the English press by an incompetent government. Another motion censuring the government was carried amid loud cheers. Three cheers for Shenandoah brought to close “one of the most disorderly meetings which has ever been held in Melbourne.” And so it went, politics both as serious business and as entertainment and everybody had an opinion. Not much has changed.

The Melbourne Herald proclaimed: “Peace is what the southerners ask for; peace meaning recognition and a new empire. The Federals declare there shall be no peace without submission and their dictatorship.” The North had no more chance to conquer the South than had Cornwallis. Australia need not trouble itself much either way, concluded the editors, but they wished to be clear on the subject: Europe had acknowledged the Confederate States as belligerents and ought to have declared the South an empire. While deploring the misery caused by such destruction, “we cannot but recognize and fraternize with the brave men who uphold their country’s flag at the risk of being hanged at the yard-arm…unrecognized by the Great Powers of Europe, and fighting against one of the mightiest in the universe.” [ii]

In a conflict replete with irony, here is one more: that sympathy for the Confederacy in Great Britain was concentrated in ruling elites of title and wealth identifying with aristocratic Southerners and fearing Yankee democracy—the “tyranny of the mob”—while many people of colonial Melbourne, more in tune with radical politics and the expanding franchise, favored the South as a champion opposing tyrannical central government. These Melbournians were on the wrong side of the war and the right side of history.

February 19, 1865: Confederate troops evacuated Charleston, the cradle of the Confederacy, to the encircling host of General Sherman. On that same day, the CSS Shenandoah sailed from Melbourne—repaired, resupplied, and with forty five new (illegal) crewmen, ready to courageously execute a mission that no longer mattered. The people of Melbourne returned to routine, continuing a march to independence of their own and a close friendship with the United States of America that endures to this day.

[i] Pearl, Rebel down under, 104-110. This and following related paragraphs.

[ii] Melbourne Herald, 4 February 1865.