Getting “Friend-Zoned” in the Civil War

At some point in a dwindling romantic relationship, most people hear or say something along the lines of: it’s not working out, but we can still be friends. Today this prophecy, which rarely amicably pans out as intended, is referred to as the “friendzone.” But the phenomenon existed far earlier than the complications of updating a Facebook relationship status.

At some point in a dwindling romantic relationship, most people hear or say something along the lines of: it’s not working out, but we can still be friends. Today this prophecy, which rarely amicably pans out as intended, is referred to as the “friendzone.” But the phenomenon existed far earlier than the complications of updating a Facebook relationship status.

During my research on the November 7, 1863 battle at Rappahannock Station, in Fauquier County, Virginia, I discovered in the bound volumes at Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park a transcribed diary of a Georgia soldier distracted during the campaign by the pangs of love. His misery off the battlefield reminds us of the humanity of these soldiers and their backgrounds and emotions which can complicate a general’s strategy.

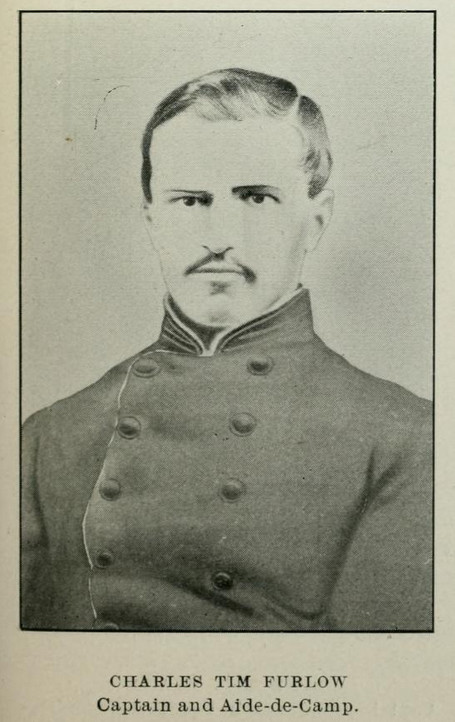

Charles Timothy Furlow was born near Holton in Bibb County, Georgia, on April 15, 1842. From a well-off family, Charles enrolled at Emory College but joined the Confederate army before graduation. On May 27, 1861, he enlisted as a private into Company K of the 4th Georgia Infantry.

The Georgian left behind his sweetheart, Miss Cora C. Solomon, but thoughts of her lifted his spirits during trying times. After the engagement at South Mountain during the tumultuous 1862 Maryland campaign, he wrote a letter to her using his cartridge box as a desk. “I thought it quite romantic,” he declared, “sitting on one of the highest mountains of Maryland, with cannon and musketry firing all around me writing to one, who, I thought, at that time, loved me.” Three days later, having survived the bloodbath at Antietam, he carved her name into the stock of his rifle.

On November 20, 1862, he was appointed orderly to Brigadier General George Pierce Doles.

Furlow returned to Georgia on furlough in March 1863 and extensively courted his sweetheart in Milledgeville. “Had a most excellent time,” he wrote, “felt like I wanted to live where I could see her every minute during the day.”

He asked for her hand in marriage before returning to Virginia. The couple made arrangements to do so at the end of the war, but Charlie harbored regret that they had not made plans for an earlier date. Regardless, he left enamored of their future together, “feeling like I never did love anyone before.”

Furlow appears to be a rather relatable soldier. Surrounded with carnage at Antietam that exceeded all he had previously witnessed in his service, he found comfort in a chew of tobacco offered by a comrade. “In the enjoyment of it I forgot all about the danger,” he wrote. During the Gettysburg campaign, he commented on his unit’s determination to drink all the whiskey they could get their hands once they hit Pennsylvania. Reaching Carlisle, he found the city contained “the largest quantity of lager beer.”

Furlow appears to be a rather relatable soldier. Surrounded with carnage at Antietam that exceeded all he had previously witnessed in his service, he found comfort in a chew of tobacco offered by a comrade. “In the enjoyment of it I forgot all about the danger,” he wrote. During the Gettysburg campaign, he commented on his unit’s determination to drink all the whiskey they could get their hands once they hit Pennsylvania. Reaching Carlisle, he found the city contained “the largest quantity of lager beer.”

He was slightly wounded in the following battle at Gettysburg, but remained with the brigade for their return to Virginia. Settling into camp in September, his world came crashing to a halt.

“I received a letter from my sweetheart, breaking off our engagement and discarding unconditionally,” he chronicled. “The letter took me entirely by surprise, as the letter previous to this one was all that I could have desired.”

A vexed Charlie immediately wrote a letter in return “as cold as I could write it, which greatly tended to widen the breach.” He immediately sent another letter in which he “repented of my course” and asked for an explanation of the broken engagement. Time passed without a response and Charlie “despaired of ever receiving an answer.” He believed “she had treated my letter with silent contempt.”

Finally a letter from Cora arrived on October 22. “Her letter was short, but to the point.” Cora wrote that from the coldness of the first letter Charlie sent, she didn’t think he cared whether he received an explanation or not. But Cora did state that “she would like for us to be friends, as we could never be anything more.”

At first Charlie believed the cause of the broken engagement were rumors about his own behavior in camp, but he later learned that Cora had found another suitor back in Georgia.

In rejection, Charlie exhibited the five stages of grief with his diary entries.

Denial

September 12, 1863: Her action in this manner was based entirely upon rumors, which when examined into, were found to be without the slightest foundation.

Anger

October 25, 1863: I wish she would give me the author of the rumors. I would like to know the person who is so low, so mean, so despicable, and so lost to all sense of honor as to thus clandestinely attempt to destroy the happiness of a man who has never injured him,—perhaps seen him. I will find out some day, I guess, if I live to get out of this war.

Bargaining

October 25, 1863: After supper I concluded that I would write my ex-sweetheart a letter, to see if I could bring matters to rights. I told her that I had acted hastily when I wrote that cold and indifferent note from Orange C.H.—that I had bitterly repented of it ever since—that I was maddened to think that there was some one who was secretly and causelessly striving to destroy my happiness. Asked her to forgive me—told her that I had never ceased to love her—had never intentionally done anything to hurt her feelings or make her think less of me. Hope this letter may have the desired effect.

Depression

November 1, 1863: This is a beautiful Sunday morning, just such a one as I used to love to see at home, when I could dress up clean, feel like a white man, and go to Sunday School and Church; after which I could return home, get a good dinner and enjoy a pleasant afternoon with the family. But those days have passed, perhaps, never to return. I was lighthearted and happy then, with no cares whatever, endeavoring with longing eyes to pry into the future and looking to it as the happiest portion of my life. I am not old now, but I have lived long enough to heave those happy illusions dispelled by the dark clouds of reality. Notwithstanding the beauty of the day I am not happy.

Acceptance

November 1, 1863: If such is the case, I am perfectly satisfied. If she could so grossly deceive me as all that, I am glad that I could not marry her. I wish the lady I marry to be frank and candid in all things.

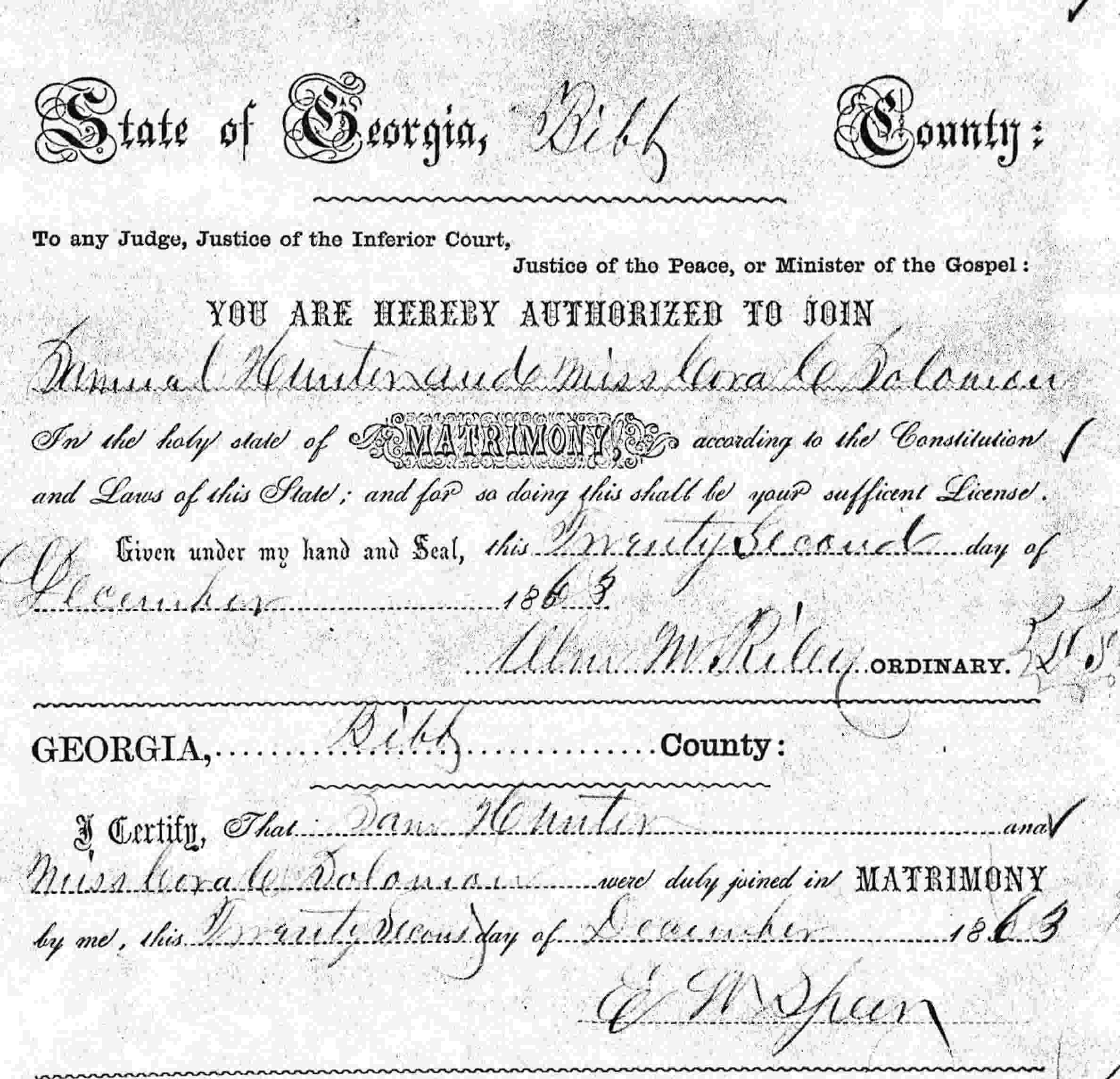

On December 22, 1863, Cora married Samuel B. Hunter, a prominent citizen and leading lawyer of Macon, Georgia. As can be expected, Charlie didn’t take this news well:

Tonight, I learn, Miss Cora Solomon married Capt. Saml. Hunter. Just three years ago, this week, I became acquainted with her. We commenced a little innocent flirtation which afterwards grew into the strongest kind of love on my part and she professed to entertain the same feeling towards myself. Affairs progressed very well for two years, interspersed occasionally of course, with those little ups and down incident to the love affairs of young people. At the end of two years everything appeared to be settled and for six months thereafter our love moved on as steadily and unruffled as possible when very unexpectedly I was discarded for some imaginary wrongdoing on my part and my most strenuous efforts and denials proved alike unavailing and tonight she marries another man. Such is woman!

Charlie’s flair for the dramatic occasionally manifested itself on the battlefield. In Henry Walter Thomas’ History of the Doles-Cook Brigade, Charlie’s brush with death is described:

“After being wounded in the head at Spotsylvania he sat down at the root of a tree, fully convinced that his skull had been torn off by a bursting shell. The blood was trickling down his face, and he was regretting his misfortune and thinking of the near approach of death, when one of his company, in passing, asked him if he was badly wounded; he replied that his wound was mortal. His friend examined and reported the wound a very slight one; after this assurance he realized his mistake and again entered the fight.”

Nevertheless, Thomas stated that his comrades were proud to serve with “such a manly little man as Captain Furlow.” General Doles frequently commended Furlow, who was promoted captain and assistant adjutant general, in his official reports.

In the end, things worked out for Charles. Though he spent the latter parts of the war in Salisbury, North Carolina battling typhoid fever, this allowed him to marry Caroline Virginia Meriwether on July 19, 1864. His eighteen year old bride was regarded as a “well-known and highly esteemed woman, with friends in many parts of the state.

In the end, things worked out for Charles. Though he spent the latter parts of the war in Salisbury, North Carolina battling typhoid fever, this allowed him to marry Caroline Virginia Meriwether on July 19, 1864. His eighteen year old bride was regarded as a “well-known and highly esteemed woman, with friends in many parts of the state.

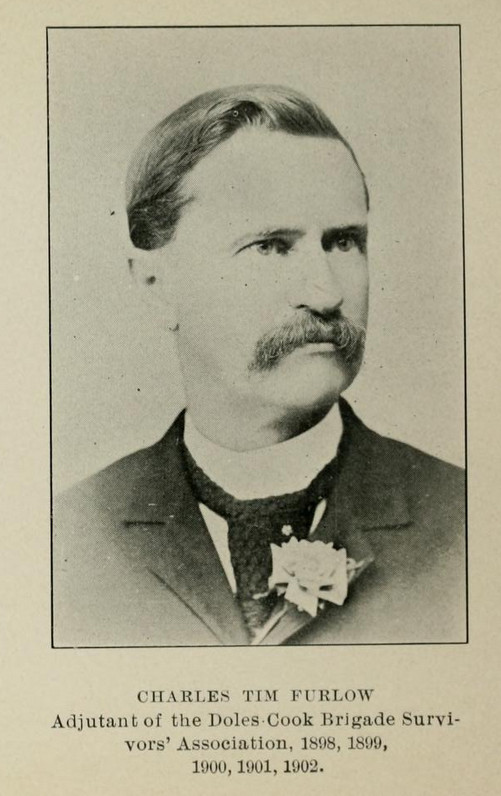

In 1884 he was appointed chief clerk in the office of the Comptroller General. Twelve years later he resigned to become Assistant Treasurer of Georgia. Charles and Caroline raised a large family until Caroline’s death in 1910. Charles died September 4, 1919, after a blessed life in the company of his loved ones.

Love the post. What happenend to Cora and Samuel Hunter?

Thanks for reading, Simon. From browsing records on Ancestry.com, it appears that Cora and Samuel had three children before Samuel’s early death in 1871. Cora then married Robert A. Nisbet around 1876 and had four sons with him. The 1900 census shows the Hunter and Nisbet children all sharing the same roof in Macon. Cora died on March 2, 1923.

Oh, that dreaded line: “Let’s just be friends.”

How about, Let’s just be ENEMIES! :-O

Dear John,

No kidding! I guess we shouldn’t be too surprised to see this popping up before the twentieth century.