“I could not answer for what might happen.” Part II

Dwight Hughes (Read Part I)

Confederates took every advantage of their status as a formal belligerent in international law, insisted on their rights, and were equally determined to devastate Yankee trade. Their government could contract loans, purchase arms and ships in neutral nations, and commission cruisers with power of search and seizure on the high seas. Men-of-war flying the Rebel flag were to be accorded the same status as those of any other nation, including the United States, and were to be treated fairly with regard to assistance, supplies, and repairs in neutral ports.

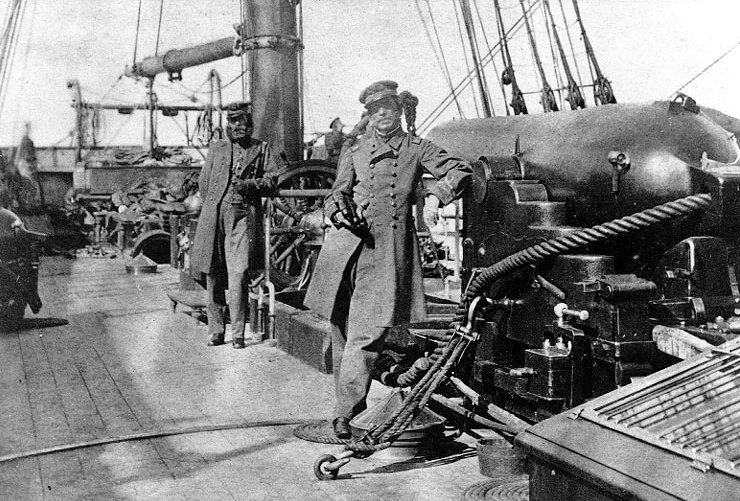

Confederate vessels entering foreign harbors invariably were blockade runners or commerce raiders. Blockade runners originated from and operated mostly out of Europe and islands near the American coast—Bermuda, Nassau, Cuba. But cruisers ranged much more widely becoming highly visible international representatives of the Confederacy. The first of these, the little screw steamer CSS Sumter, had been a test case for neutrality and a precursor for those that followed. She slipped past New Orleans blockaders in June 1861 and under Captain Raphael Semmes (later of the Alabama) captured and destroyed Union shipping until trapped at Gibraltar in April 1862. She entered British, French, Spanish, Brazilian, and Dutch harbors in the Caribbean and South America for supplies and repairs and to dispose of captured vessels.

In November 1861, the CSS Nashville became the first Rebel cruiser to visit Great Britain and was received with open arms. Wherever Confederate cruisers appeared, U.S. embassy and consular authorities, with actual or implied backing of the U.S. Navy, vehemently opposed any support whatever, insisting that these were simply rebels and pirates and should be treated as such despite official belligerent status. But Rebel raiders were welcomed warmly in ports of the empire including Jamaica, Trinidad, and Gibraltar, especially by colonial governors and army and navy commanders. The Alabama caused a stir in Cape Town in August 1863 with parties and balls in her honor; Shenandoah was treated similarly in Melbourne in January 1865.

Several Rebel raiders, including the most effective of them—Alabama, Florida, and Shenandoah—along with numerous blockade runners and a few ironclad warships were British built, armed, equipped and at least partially manned. Central to the controversy was the legality of such vessels as legitimate articles of non-contraband neutral trade, along with British obligations to accord them equal status with United States warships. A great deal of money was being made selling to both sides. The near escape of the ironclad Laird rams into Confederate service was, other than the infamous Trent affair, possibly the closest the two nations came to war.

In November 1861, Captain Charles Wilkes of the USS San Jacinto on his own initiative forcibly removed Confederate emissaries James Mason and John Slidell from the British mail packet Trent. Outrage exploded in Great Britain over this egregious violation of their neutrality. Under threats of war, Lincoln was compelled to back down and release the Rebels. The Alabama’s dramatic and destructive two-year cruise became a cause celebre, which, along with her sisters, demonstrated the pitfalls of neutrality and caused extreme acrimony between the two nations.

International trade had expanded three hundred percent in the early nineteenth century, much of it carried in American vessels produced by the burgeoning Yankee shipbuilding industry. During the Civil War, only one in a hundred Union vessels sailing in foreign trade actually was taken by Confederate commerce raiders, but the major impact had been psychological, the real damage done by fear of capture. Eight Confederate warships destroyed over 100,000 tons of Union shipping worth $17 million, but drove another 800,000 tons into foreign ownership with British and others eagerly buying them.[1]

Tonnage shifting to British colors climbed from 71,000 in 1861 to a total of 921,000 tons, or about a thousand ships, by the end of the war. Marine insurance rates soared, reaching as high as eight percent in 1863. A merchant may have had to pay as much as $800 more to insure $10,000 worth of cargo shipped under the American flag. So to stay in business, Yankee shippers sold their ships; many that remained were too old or rotting to be of interest to buyers. This was called the flight from the flag.[2]

Some of the finest ships in the American merchant marine including seventy-four clippers transferred to foreign ownership between 1861 and 1865. One of the most celebrated, the Flying Cloud, was “sold British” in 1862. Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase admitted that the cruisers had a direct impact on fiscal policy and exchange rates. New England emerged from the conflict with about half of its prewar registered tonnage. Burned and sunk vessels were lost forever, while those that shifted flags were never allowed to return to American registry. The war brought maritime New England’s golden age to a close, mostly to the benefit of the British, many of whom were delighted at this humbling of their only serious rival in ocean trade.[3]

Navy Secretary Welles bemoaned to his diary: “It is pretty evident that a devastating and villainous war is to be waged on our commerce by English capital and English men under the Rebel flag with the connivance of the English Government, which will, and is intended to, sweep our commerce from the ocean.” U.S. Minister in London Charles Francis Adams put it this way to the British foreign secretary in April 1865: “The United States commerce is rapidly vanishing from the face of the ocean, and that…of Great Britain is multiplying in nearly the same ratio.” [4]

This was, Adams contended, directly the consequence of British, “acknowledging persons as a belligerent power on the ocean before they had a single vessel of their own to show floating upon it,” and thereafter treating it as such. In other words, the Kingdom of Great Britain must be regarded, “as not only having given birth to this naval belligerent, but also as having nursed and maintained it to the present hour.”[5]

The British paid for their entrepreneurship after the war: They agreed to an international tribunal, which in 1872 arbitrated a suit brought by the Unites States for damages arising from support for Confederate raiders, called the “Alabama Claims” after the most famous of them. The tribunal found in favor of Great Britain in all cases except Alabama, Florida, and Shenandoah, and awarded compensation of $15.5 million, which was duly paid in gold coin. The British considered this a minor cost for their ongoing domination of global trade, and for assuaging the deep anger from across the Atlantic over Britain’s role in the late unpleasantness.

The Union blockade significantly interrupted Southern trade, degraded the Confederacy’s capability to wage war, and contributed to its defeat. On the other side, Rebel commerce destruction put not a dent in the industrial war machine of the Union as trade shifted to neutral vessels. Alabama and her sisters, however, did cripple powerful northeast shipping and whaling industries; they made a notable impact on Northern morale, and stoked virulent anti-war sentiment demanding peace even at the expense of splitting the nation. It was a blow from which the United States merchant service never recovered.

Cruiser exploits also greatly boosted the spirits of Southerners who revered the ships and lionized the men. They proved that the Confederacy could carry the fight to the Union anywhere in the world, exacerbated international tensions, and encouraged England and France to consider intervention and support. One historian concluded: “The cruisers were not able to win the war, but relative to their cost they did far more damage…than any other class of military investment made by the Confederacy.” Commerce warfare paid dividends on both sides.[6]

[1] Chester G. Hearn, Gray Raiders of the Sea: How Eight Confederate Warships Destroyed the Union’s High Seas Commerce (Camden, ME: International Marine Publishing, 1992), xv.

[2] George W. Dalzell, The Flight From The Flag: The Continuing Effect of the Civil War Upon the American Carrying Trade (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1940), 237-248.

[3] David Donald, ed., Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet: The Civil War Diaries of Salmon P. Chase (New York: Longmans Green, 1954), 234-5.

[4] Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles: Secretary of the Navy Under Lincoln and Johnson, 3 vols. (Boston.: Houghton Mifflin, 1911), 1:250; Mr. Adams to Earl Russell, Case of Great Britain as Laid Before the Tribunal of Arbitration Convened at Geneva…. 3 vols. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1872), 1:766-768.

[5] Mr. Adams to Earl Russell, Case of Great Britain, 1:766-768.

[6] Frank Lawrence Owsley, Jr., The C.S.S. Florida: Her Building and Operations (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1965), 10.

Enjoyable article. Thank you.