Welles and Fox: Dynamic Duo of the Deep (and Shallow)

Lee and Jackson, Grant and Sherman—celebrated partnerships of the Civil War. But there was another highly successful team, which receives less credit than is due: Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Assistant Secretary Gustavus Vasa Fox.

Almost nothing in the history and traditions of the United States Navy prepared it for the challenges of civil war. In 1860, it was with few exceptions still cruising in small, semi-permanent squadrons on far-flung stations to show the flag and protect trade while training to refight the War of 1812—glorious single-ship duels against a foreign foe and commerce warfare with pirate suppression as needed.

Operations such as blockade, reduction of shore fortifications and heavily defended ports, shallow-water coastal and riverine warfare, combined army/navy operations, and capture of commerce raiders were in almost no one’s imagination.

The navy had come a long way since its baptism of fire during the undeclared war with France in 1798. A more efficient organizational structure had replaced ad hoc administration of the past. A formidable corps of officers with proud heritage, high esprit, and expert seamanship (which would serve both sides) had explored much of the world’s oceans in the first half of the century, protecting the burgeoning American shipping and whaling industries. Officer education had—against conservative resistance—been formalized and modernized at the new Naval Academy in Annapolis. A body of trained enlisted men served the fleet, while flogging had been outlawed as a disciplinary punishment and alcohol would be banned afloat in 1862.

The fleet was advancing rapidly in steam and propeller propulsion, and leading the ordnance revolution of the era. However, strategic and tactical vision were lacking. Slow promotions caused discontent among junior officers. The technology of ironclad vessels had been largely ignored—a failing with nearly dire consequences. And as events would prove, manpower, material, and infrastructure were totally inadequate to the mission.

That both sides faced the coming conflict with singular lack of foresight or preparation seems incredulous in hindsight; such naiveté appears to be an American characteristic. But the pre-war navy was a small, closely-knit brotherhood in a most esoteric profession, most of whom—shipmates at sea—did not wish to think very deeply about fighting each other over distant domestic differences. They could not possibly envision what did happen or the immense effort required.

As guns opened at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, other quintessentially American attributes manifested themselves: Determination, adaptability, innovation, and daring, along with occasional blundering, extended naval operations into domains of strategy, tactics, and technology heretofore unknown. More than any other contest before or since, the U.S. Navy reinvented itself in the fight, starting with a third-rate force but exploding tenfold into one of the most powerful and technologically advanced fleets in the world, which contributed mightily to victory and then was promptly dismantled.

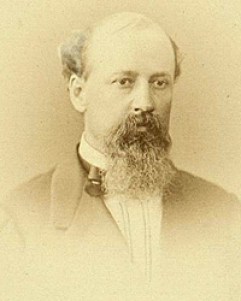

Overseeing this naval revolution was one of the most dynamic partnerships of the war: Welles and Fox. Secretary of the Navy Welles was a dour Connecticut Yankee and former newspaperman appointed (as were other Lincoln appointees) primarily to maintain political and regional balance in the cabinet. On a bald pate, he sported an old light-brown wig that no longer matched the luxuriant, snowy beard. He was excitable and voluble. Secretary of State William Seward among others considered him comical and unsophisticated.

The new secretary’s only experience in naval matters had been as head of the Bureau of Provisions and Clothing in the 1840’s, which at least provided familiarity with terminology and procedures. Welles frequently complained to his diary about perceived failings of fellow cabinet members, and was a jealous rival of the assertive Seward, especially when the Secretary of State meddled in naval affairs, as he was wont to do.

But Welles was an astute politician and conscientious administrator, fair-minded and generous in praise of others, who placed high value on order and procedure. He took an especially hard line with officers whose devotion to the Union was suspect, and stood up to the president when deemed necessary. The new secretary systemized officer ranks corresponding to the army. He convened examining boards to force superannuated officers into retirement, and advanced the principle of promotion on merit and combat experience. Under Welles, the department was largely free of corruption and graft. Most of these administrative changes remained in place long after his departure in 1869.

The assistant secretary of war wrote that Welles was, “a very wise, strong man. There was nothing decorative about him; there was no noise in the street when he went along; but he understood his duty and did it efficiently, continually, and unvaryingly.”[1] The president would come to rely on him for steadfast loyalty, honesty, and passion in matters extending well beyond the naval, affectionately referring to the secretary as “Father Neptune.” Welles’s wife, Mary Jane, was one of the few good friends of Mary Todd Lincoln. Mrs. Welles had lost six children of her own, and although sick with a heavy cold, spent the night of Lincoln’s assassination and following day with Mrs. Lincoln.

The organizational simplicity of the navy department (and federal government generally) stands in stark contrast to the labyrinthine leviathan in place today; in comparison with the fleet, the administrative apparatus expanded little.

Welles increased staff bureaus from five to eight in July 1862. Their names indicating functions, they were the Bureaus of: Yards and Docks; Equipment and Recruiting; Construction and Repairs; Steam Engineering; Provisions and Clothing; Ordnance; Navigation; Medicine and Surgery.

The total number of department clerks and draftsmen grew from thirty-nine to sixty-six during the war years to manage records, correspondence, and budget and spending actions. Bureau chiefs oversaw day-to-day administration. Most were competent and conservative administrators, and the system worked remarkably well considering the unprecedented challenges. But there were problems, primarily that the bureaus operated as independent fiefdoms with insufficient coordination and cooperation.

Two bureau chiefs stand out both for outstanding service and as leadership challenges for Welles and Fox: John A. Dahlgren at the Bureau of Ordnance and Benjamin F. Isherwood of the newly created Bureau of Steam Engineering.

The craggy faced Dahlgren had been a pioneer in the ordnance revolution of the pre-war navy; he was promoted over his peers to bureau chief in 1862. Lincoln visited Dahlgren frequently at the Washington Navy Yard, consulting him as friend and confident on naval affairs. Over the objections of Secretary Welles, the president later sponsored the ambitious, but relatively junior and inexperienced, Dahlgren to command the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron.

The Bureau of Steam Engineering reflected an increased reliance on mechanical propulsion and the revolutionary role science and technology played in the mid nineteenth-century navy. A pioneer in naval engineering, Isherwood was appointed Engineer-in-Chief to head the bureau. He was a dynamic, energetic leader with a scientific and practical mind, who struggled to constrain the rapidly expanding complexity of steam engineering within the capabilities of poorly educated engineers flowing into the navy. Isherwood also was ambitious, outspoken, and occasionally confrontational; he was not a friend of the touchy John Ericsson, inventor of the Monitor.

Welles established at hoc boards and offices, usually staffed by serving officers, to work particular problems. The Blockade Strategy Board would do invaluable service, becoming in effect a strategic planning staff. A temporary committee was convened to deal with the Confederate ironclad under construction in Norfolk, which would become the CSS Virginia and a potentially decisive threat for which the U.S. Navy had no counter. The committee reviewed designs for proposed ironclads and settled on three, including the Monitor.

A nation of tinkerers began to deluge the department with well intentioned, but often harebrained ideas, inventions, and schemes. With no research and development apparatus, Welles tapped famed physicist and first Secretary of the Smithsonian Initiation Joseph Henry as leader of a group of scientists, called the Permanent Commission, to advise on all scientific questions brought before it by the Navy. It was the first government-sponsored research organization and would become forerunner of the National Academy of Sciences.

Welles also was a good judge of character and abilities, who recognized the need for competent subordinates and was willing to delegate accordingly, especially regarding the deluge of work at the start of the war. To compensate for his own professional shortcomings, Welles wisely recruited Fox, creating the new post of assistant secretary specifically for him.

Fox was a Massachusetts woolen mill executive and former navy officer with eighteen years’ service including a circumnavigation of the globe, the Mexican War, and command of several mail steamers. He was of unprepossessing appearance and medium stature with a pear-shaped form and piercing eyes. Fox impressed Welles in early 1861 by submitting an unsolicited proposal for an army-navy expedition to relieve the garrison at Fort Sumter. Although the plan did not come to fruition, it demonstrated notable aggressiveness and encyclopedic knowledge of naval affairs.

Vocal and outgoing at all times, Fox could be brusque and impatient when impeded, but he also displayed a lively sense of humor with a preference for good company, good food, and good wines; he was a delightful companion. The president was charmed by his company, often consulting Fox at the White House or visiting his home at night. Mrs. Lincoln was friendly with Fox’s wife, Virginia Woodbury Fox, to whom she sent flowers from the White House gardens. Fox also was brother-in-law to Montgomery Blair, Lincoln’s postmaster general, a member of the politically powerful Blair clan.

Presidential aide John Hay called Fox, “an incarnation of inexorable energy” with “a powerful mind and an iron constitution” engaged in “relentless and unceasing labor for the cause to which he is heart and soul devoted.”[2] The assistant secretary was unfairly charged on several occasions with decisions that his chief had made or errors that were the secretary’s responsibility. Yet he was intensely loyal and never complained, a quality that Welles prized above all others.

Fox’s judgment was not flawless: driven by self-confidence and overwork, he could jump to conclusions and stick stubbornly to them despite contrary evidence. Most notably, his near obsession with the revolutionary fighting capabilities of the Monitor class ironclads, over the considerable reservations of senior commanders, led to a disastrous attempt to take Charleston harbor in April 1863. Fox also was complicit late in the war (along with lack of coordination between bureaus) in the fiasco of the “light draft” Casco class monitors, which turned out to be completely unseaworthy and useless, wasting millions of dollars.

While the secretary managed politics and general policy, his assistant became in effect a chief of naval operations, overseeing daily operations of the department. Fox would often take a lead role in determining and executing strategy, sometimes directly interacting with the president; he could even override Welles without contradiction. Welles and Fox: They were an informal but widely respected and highly effective team. The results speak for themselves.

[1] Harold Holzer, Lincoln President-Elect: Abraham Lincoln and the Great Secession Winter 1860-1861 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008), 209.

[2] Michael Burlingame, ed., Lincoln’s Journalist: John Hay’s Anonymous Writings for the Press, 1860-1864 (Southern Illinois University Press, 1999), 155.

I first “met” Gus Fox in May, 1861. Fox was the officer who brought President Lincoln word of the death of Elmer Ellsworth. Many think EE was just some sort of anomaly–not really important. When looking at his life, however, so many men who ran the Union side of the war are somehow part of the story. I see this as a combination of Ellsworth’s status, and as a show of respect for Lincoln himself. I often think about Fox handing that telegram to AL, watching the President’s face change to unutterable sadness at the death of a friend.

Thanks for this article. Let’s have more of Fox–his attempt to provision Sumter is one of the best stories in a war filled with “best” stories.

Thanks Meg. Yes, Gus (and his boss) will be back. Both are fascinating characters.

Three cheers! I think both Welles and Fox are underestimated. Neither gets enough credit for expanding the Navy and prodding it to aggressive action. Look forward to follow-up pieces on Dahlgren and Isherwood.

Gideon Welles: one of my favorite cabinet members! 😉