Longstreet Goes West, part seven: A parting of the ways

On October 30th, Bragg dispatched an angry telegram to Jefferson Davis, then in Savannah, headed back to Richmond. Bragg outlined his frustrations with Longstreet, and the lack of effective action in Lookout Valley. On the 27th, wrote Bragg, Longstreet was ordered to attack with three divisions. No attack followed. “That night, . . . Longstreet asked for another division as a support. . . . It was given. He informed me he [Longstreet] should attack with one brigade. I ordered him not to do so with less than a division. He moved a division to the vicinity, but attacked with one brigade. . . . We have thus lost our important position on the left . . .”

The next day, after another round of acrimonious dispatches flying between Bragg and Longstreet, the outraged army commander sent a follow-up to Davis: “Further correspondence of a more disrespectful and insubordinate character is received from the general. Copies will be sent.”

Davis must have been dismayed. The Confederate President had his own strong views on what should have occurred once the Federals crossed the Tennessee: On October 29, before he even knew of Longstreet’s repulse at Wauhatchie, Davis detailed those ideas: “As you have a shorter and better road . . . [between Chattanooga and] Bridgeport, that you will be able to anticipate him, and strike with the advantage of fighting him in detail.”

As we have seen, this was an unrealistic expectation, given the Confederate logistical limitations. Either Bragg earlier failed to fully explain those limits to Davis, or perhaps Bragg himself didn’t fully realize the extent of those limits – which, if true, was a damning indictment of Bragg’s own negligence.

So far, Longstreet had largely escaped any of the consequences of his opposition to Bragg. Other generals were relieved or re-assigned, but Davis generally preferred to smooth over troubles rather than confront them, and he was not interested in letting Bragg continue that purge. In that same October 29 dispatch, Davis explained: “The removal of officers of high rank, or important changes in organizations, usually work evil, if done in the presence of the enemy. . . . I prefer to postpone the consideration of any further removal of general officers from their commands, and relying on the self-sacrificing spirit which you [Bragg] have so often exhibited, must leave you to combat the difficulties arising from the disappointment or discontent of officers by such gentle means as may turn them aside.”

In other words, ‘General Bragg, you figure it out. I’ve got a war to run.’

By November 1, however, in light of Bragg’s latest complaints, Davis suddenly seemed more fully in Bragg’s corner. The botched fight at Wauhatchie, said Davis, “is a bitter disappointment. . . . Such disobedience of orders and disastrous failure as you describe cannot be consistently overlooked. I suppose you have received the explanation due the Government, and I shall be pleased if one satisfactory has been given.

Longstreet now seemed on the brink of losing his command. That, however, did not happen.

The reason why is that somewhere over the course of those few days between October 29 and November 3, Longstreet and Bragg – superficially, at least – worked through their mutual difficulties. Bragg showed Longstreet Davis’s October 29 letter, which seemed to help; Longstreet withdrew his previous communications – those which Bragg found “disrespectful” and of “insubordinate character.” Additionally, the arrival of Hardee, specifically tasked by Davis to help heal the ongoing rift between Bragg and his subordinates; and the arrival of Howell Cobb helped to avert further disruption

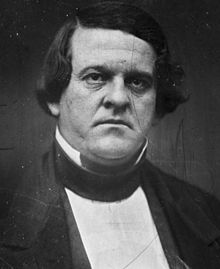

Cobb was a former Speaker of the US House of Representatives, a former Secretary of the Treasury under President Buchanan, a former president of the Confederate Provisional Congress, and a Confederate Major General. He had Davis’s ear, and carried sufficient gravitas in both the political and military realms as to gain the attention of everyone involved. In the fall of 1863, Cobb commanded the Georgia State Troops (a branch of the state militia, basically) whose mission included protecting Bragg’s lifeline, the Western & Atlantic Railroad.

Cobb and Hardee both arrived on the 1st or 2nd of November; Cobb spending “several days” with the Army of Tennessee. In a confidential letter to Davis, written on November 6, Cobb described the state of affairs. “It is very unfortunate,” Cobb admitted, “that there does not exist more cordiality & confidence between Genl Bragg and Genl Longstreet – If that difficulty could be overcome, I believe all would be well.” More encouragingly, however, “I have reason to believe that the feeling is better than it has been.”

Hardee apparently proved his worth. Hardee, said Cobb, was “laboring earnestly (and I think successfully) to bring about cordiality & confidence where there had been the greatest need for it.”

Besides, there might be a better solution to the rift between Bragg and Longstreet, one first proposed by Davis in his letter of October 29; Bragg “might advantageously assign General Longstreet with his two divisions to the task of expelling Burnside, and thus place him in position . . . to hasten or delay his return to . . . General Lee.”

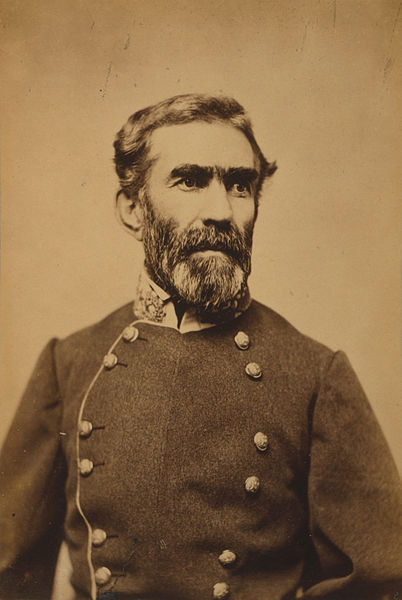

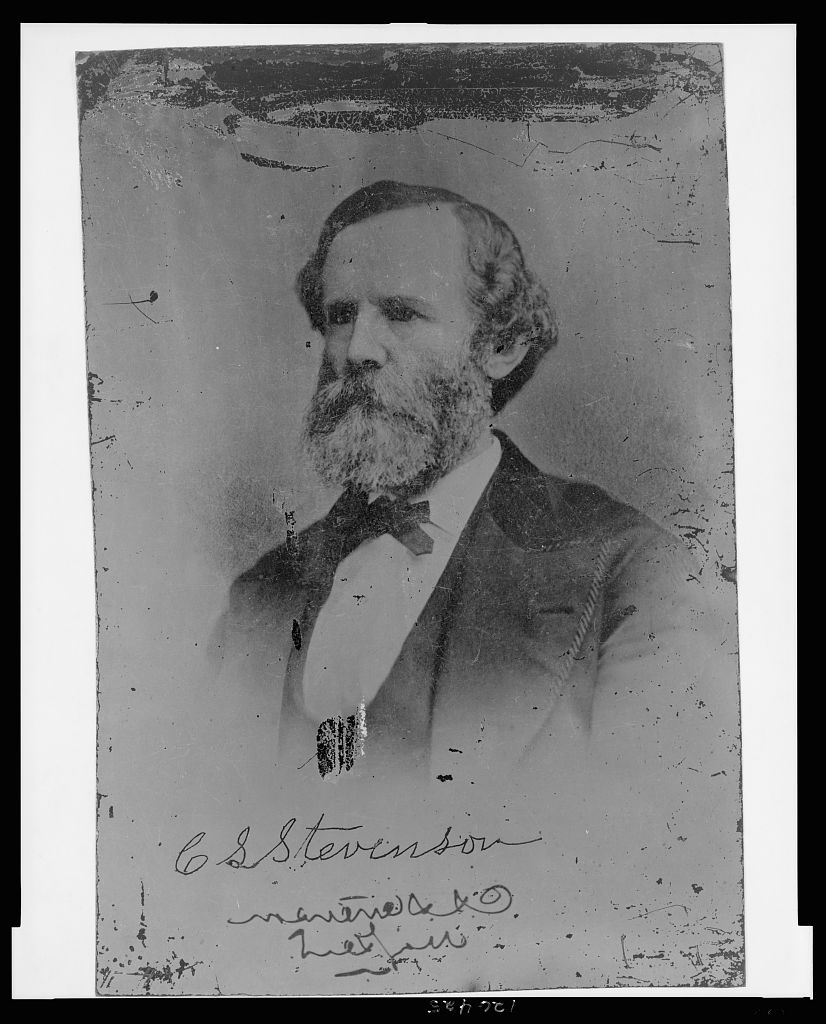

Back in mid-October, Bragg dispatched a division towards Knoxville, under the command of Major General Carter L. Stevenson, who also assumed control over those elements of Joe Wheeler’s cavalry corps operating in East Tennessee. Stevenson’s mission was to prevent Burnside from linking up with Rosecrans, and to force the Federals back towards Knoxville if possible. But Stevenson’s division was weak, numbering less than 4,000; the cavalry, perhaps another 2,000; they could do little more.

These Confederates won a small but heartening victory at Philadelphia Tennessee, on October 20, killing or capturing 479 Federals at a cost of about 100 Confederate casualties. Sensing an opportunity, on October 22, Bragg decided to reinforce Stevenson with a second division under John K. Jackson, numbering another 6,000 troops.

Now came the President’s idea of sending Longstreet into East Tennessee.

Exclusive of cavalry, on October 31, Bragg’s army numbered just under 53,000 present for duty; of which 10,000 were in East Tennessee. Longstreet and his two divisions numbered just over 11,000 troops. If Bragg swapped Longstreet for Stevenson, the net loss in combat power would be negligible. Even better, following Hardee from Mississippi were at least two more brigades of infantry, roughly another 3,000 to 3,500 men – meaning that even without Longstreet, Bragg’s forces would increase by a small margin.

Of course, the Confederates understood that large numbers of Federals were either headed for or already arrived at Chattanooga. In addtion to Hooker’s column (now in Lookout Valley) there were perhaps another 25,000 Yankees making their way from Grant’s old command, the Union Army of the Tennessee, now led by Sherman. Even without counting in Burnside’s men, Grant would soon have prehaps 85,000 men (or more) at Chattanooga. Bragg might soon be outnumbered 2-1.

Over the years, both Davis and Bragg have come in for a great deal of criticism in sending Longstreet away. Even Ulysses S. Grant leveled scornful remarks at President Davis’s supposed “military genius” in his memoirs. In fact, however, the concept was not devoid of strategic promise – just the opposite. Outnumbered armies have been beating larger foes in just this manner since ancient times; by attacking disparate or isolated elements elements of the enemy force with locally superior numbers, one after another. Militarily, the term is “defeat in detail.”

But doing so successfully requires not just better strategic sense. Such victories also require consummate operational skill, superior timing, and superior execution.

Was the Army of Tennessee capable of that level of expertise?

Reblogged this on Practically Historical.