Lost Opportunities in the Army of the Potomac—A Pair of Examples

Army management is a complicated skill in which the personality and temperament of commanders influence the inner workings and culture of the organization. The Union had no army which was as political, and influenced by outside politics, as its primary eastern theater force, the Army of the Potomac.

Political infighting and dissent is well known among the leadership of this army. Over the course of its history the force went through several commanders, a result of internal in-fighting, presidential intervention, and pressure from Congress.

Many officers passed through the army and either retired or were transferred, again partly a result of politics or squabbling. Other factors, including health or personal reasons, caused officers to depart.

Some cases are well known, such as the popular John Reynolds being killed at Gettysburg on July 1st, or Winfield S. Hancock retiring in 1864 due to ill health. Yet several other lesser-known but well qualified officers left the army as well. The loss of potential leaves us to wonder what their impact might have been.

Of course it is impossible to speculate how someone may have performed if they were promoted or even left in a current position, but several officers showed competence and promise, and their services were lost by the Army of the Potomac at a time when it needed good leadership.

This is an exercise with limitless possibilities, therefore I have chosen to focus on two generals who I was vaguely familiar with, and wanted to know more about. Each seemed to have reasonable expectations of high advancement in the army. Examining their potential is a reveals the many twists and turns that a career could take during the war, and is a reminder to keep in mind possibilities and near misses which could have altered events.

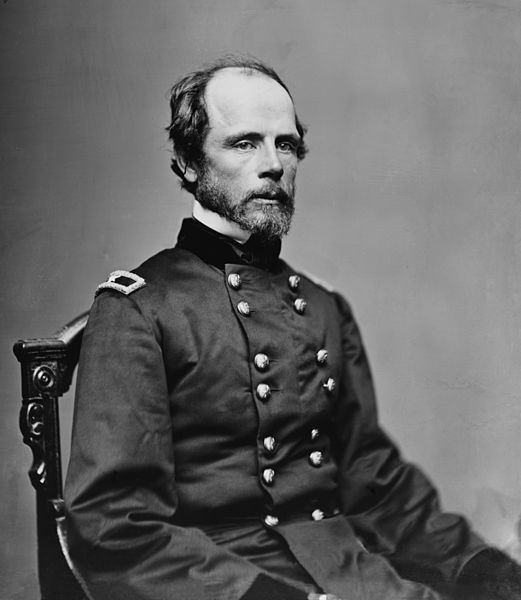

One such officer was John Peck. Born in New York State and a graduate of West Point (1843), U.S. Grant was also in his class. Following graduation Peck saw active service in the Mexican War. He was breveted twice in the conflict for “gallantry and meritorious conduct.” Peck saw brief service on the frontier fighting the Apache before retiring from the military to serve with a railroad company in his home state.

When the Civil War broke out, he was appointed a brigadier general of volunteers. His first assignment was in guarding the Washington defenses in 1861. The following year Peck led a brigade in the Peninsula Campaign and the Seven Days. n the later campaign he led the Second Division of the IV Corps. The most action they saw in the Seven Days was at Malvern Hill, where Peck’s Division held the Union right against Confederate assaults. He handled his troops with precision, reinforcing the line when needed and rotating units in and out over the course of the evening. Recognizing his actions, Peck was promoted to Major General after Malvern Hill.

After the army’s withdraw, Peck was placed in command of the garrison at Yorktown, and oversaw all Union troops on the south side of the James as well. Peck skillfully directed the defense of Suffolk in 1863, besieged by troops under Gen. James Longstreet. During the siege his horse fell with him mounted, and he was badly injured.

Following the relief of Suffolk, Peck left active service and recovered at home. Next he commanded troops in Union-occupied eastern North Carolina. Yet his injury returned to haunt him. He wrote, “On the 9th [of October] I mounted my horse for the first time since April, when my horse was thrown upon me with great violence while forming line of battle. The experiment was not as satisfactory as I wish, but I hope to recover from the blow near the spinal column.” Yet active campaigning was too much for his battered body. He later held a command along the Canadian frontier in the Department of the East, but never again served with a field army. Wills 264

After the close of the war, Peck returned to Syracuse where he became president of the New York State Life Insurance Company. His health deteriorating, he died on April 21, 1878, at his home in Syracuse.

Was his potential lost to the army? How far could he have gone up the chain of command? We will never know, of course. We do know that he conducted himself calmly and firmly during the stressful three week Suffolk campaign. He also acted coolly and decisively at Malvern Hill.

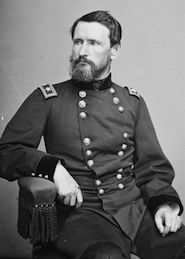

Ironically, another officer worth exploring commanded the other division of the IV corps. Rising even higher in the army’s chain of command was Darius Couch. Also a New Yorker, Couch was born in 1822 and also graduated from West Point (1846). George McClellan was a classmate. He served in the Mexican War and like Peck was brevetted for “gallant and meritorious conduct.”

He then had several garrison assignments, and saw action again in the 1849-50 Seminole Wars. After eleven years of military service, Couch resigned and worked as a merchant in New York City, then moved to a business in Taunton, Massachusetts.

When the Civil War started, Couch was appointed Colonel of the 7th Massachusetts. With his extensive experience, that fall Couch was appointed to brigade command as a general, followed by divisional command.

With the IV Corps he participated in the Peninsula and Seven Days Campaigns in 1862. His division was heavily engaged at Seven Pines, but through the Seven Days it saw little combat.

After the campaign, Couch was promoted to Major General, and led the IV Corps in the Maryland Campaign. He was so highly regarded that McClellan refused his resignation due to illness. That fall Couch was placed in command of the II Corps and led it at Fredericksburg. As part of the force fighting at the Stone Wall, his troops were in the worst of the action here.

By the spring of 1863, Couch was the senior corps commander in the Army of the Potomac, and therefore was Gen. Joseph Hooker’s second in command. Only he and Reynolds had commanded at the corps level prior to this time. He directed the II Corps during the Chancellorsville campaign, which saw Jackson’s famous flank attack on the afternoon of May 3.

At about 9 a.m. on the next day Hooker was stunned when a shell hit the pillar he was leaning on. Hooker then turned command of the army over to Couch, but gave him orders to withdraw the army to defensive lines to the north. Hooker told Couch, “I turn the command of the army over to you. You will withdraw it and place it in the position designated on this map.” Even though the other commanders (except Howard) strongly advocating staying to fight, and he was in command, Couch was given orders that prevented him having a choice.

Soon Hooker resumed command, and Couch reverted to corps command. Whether Hooker should have taken the reins back so soon is a matter of debate. Thus Couch’s stint in army command lasted about an hour or so, and he did not have discretion to act freely, being constrained by a groggy Hooker’s instructions.

Couch did not get along well with Hooker and requested a transfer following Chancellorsville. If he had stayed with the army, might he have led it at Gettysburg? What if Darius Couch had gritted his teeth to serve with Hooker, then replaced him when Hooker separated from the army?

Instead, Couch was reassigned to the Department of the Susquehanna, where he was still involved with repelling Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania.

Couch deftly worked with Governor Andrew Curtin to coordinate the state’s defense, and managed a cobbled force of regular troops and Pennsylvania militia to defend Harrisburg.

Couch oversaw defense of the Keystone State again in 1864 during McCausland’s Chambersburg raid. Transferred to the west, he commanded the XXIII Corps of the Army of the Ohio in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign and for the remainder of the war. Couch finished his military service by commanding a division with the XXIII Corps the Carolinas Campaign in 1865.

Following the war, Couch returned to civilian life in Taunton, and ran unsuccessfully as a Democratic candidate for Governor of Massachusetts in 1865. He briefly served as president of a mining company in West Virginia, then moved to Connecticut where he was Adjutant General of the state militia. He died in Connecticut in 1897.

Here are just two examples of lesser-known leaders who proved they had talent and determination. How might the Army of the Potomac have benefitted from their leadership and skill?

Twists of fate always leave us wondering. Many of us have asked, what if Jackson hadn’t been shot at Chancellsorville, but how many have asked, what if John Peck hadn’t fallen from his horse at Suffolk? Or what if Darius Couch had replaced Hooker after Chancellorsville?

I have also wondered a good deal about Darius Couch’s potential, but simply do not find anything more than ‘competent’ about his performance as Corps and Division commander in the east and the west. He seems to generally have his men where the higher headquarters wanted them, but never delivered any great strokes on the battlefield. In the west, especially, he seems merely a passive presence; absent from the field of Franklin, and simply stolidly supporting Schofield’s hesitation on the field of Nashville until Thomas kicks them both into motion and action. I believe Jacob Cox actually led XXIII at Franklin.

I like the notion of somebody being kicked into motion by Thomas at Nashville. 🙂

Haha, yes!

Yes, David, perhaps he was simply competent- not brilliant but not above his head in command at this level. Many don’t know that he was that high in the command structure of the Army of the Potomac, or that he briefly led it. Its just a fascinating what-if. Thanks for commenting!

An interesting post. I would add Israel B. Richardson – an aggressive, successful division commander who was also very well-connected to the Michigan GOP, Chandler, et al. Phil Kearney without the flash and with a little more restraint. There are those who think Richardson was ticketed for higher command when he was MW at Antietam.

I agree, John. I don’t know much about Richardson, but I have wondered about him. Kearny definitely would have had a long term impact on the army if he’d lived!

I don’t think it was coincidental that both Couch and Peck were from IV Corps. McClellan had no faith in the IV Corps commander (Keyes) on the Peninsula, and I am sure this led to the subordinate officers being overlooked. Couch was able to rise as far as he did by wrangling a shift to VI Corps for the Maryland Campaign.

Of course, men whose careers were cut short by enemy bullets or other forms of death are a rich source of “what if?” kind of things. We could probably construct a huge list of such folk. My favorite is CF Smith.

Yes, James, McClellan had no respect for Keyes, and perhaps that affected the careers of Peck and Couch. And yes, this line of thought could go on indefinitely.. which is kind of fun