Voices of the Maryland Campaign: September 13, 1862

This Saturday began with the cracking of rifle fire atop Elk Ridge. From behind their breastwork, the Federals made Kershaw’s South Carolinians pay for every step they took. The combined weight of Kershaw and his reinforcements under William Barksdale and the greenness of the blue-clad defenders all contributed to the fact that by mid afternoon, garrison commander Dixon Miles watched aghast as his troops tumbled off Maryland Heights into Harpers Ferry. To the west and south, “Stonewall” Jackson’s and John Walker’s commands approached Harpers Ferry ever closer, tying the noose firmly around Miles’ neck.

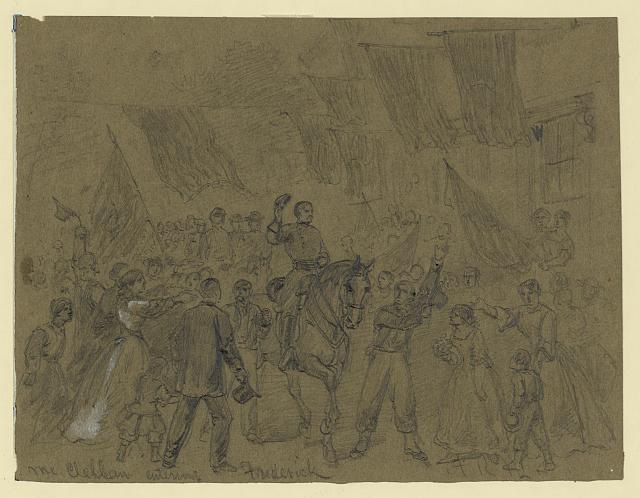

In the Middletown Valley, the Federal cavalry began asserting itself once more. Riding west and south from Frederick, they encountered Jeb Stuart’s pesky cavalrymen in two mountain passes in the Catoctin range. They ably drove the Confederates from their high-end defenses, but not without the help of the Federal infantry pressing into Frederick. It was some of those Union soldiers who, resting in a field south of the city, stumbled upon an envelope addressed to D.H. Hill. Inside, they found a lost copy of Robert E. Lee’s now famous marching order, Special Order No. 191.

George B. McClellan received this astounding find around noon or thereafter, sent it off to Alfred Pleasonton for validation and, upon Pleasonton’s report back, settled on his plan of attack the next day “to cut the enemy in two & beat him in detail” while also relieving Harpers Ferry. Robert E. Lee resolved to obstinately defend South Mountain.

Jesse Reno’s Ninth Corps, the spearhead of the Army of the Potomac the whole campaign thus far, retained that designation in McClellan’s plan for September 14. While McClellan instructed most of his army to not move until daybreak the next day, the Ninth Corps spent the afternoon and evening getting into position to either reconnoiter or force the passes of South Mountain on Sunday the 14th. George Hitchcock of the 21st Massachusetts Infantry recalled that march.

Our division is under orders to move at a moments notice and to be prepared for fighting. I therefore go to work and acquaint myself with my new friend, my Enfield rifle; take it to pieces, clean it up and then harness up and lie on arms until four in the afternoon when we are ordered forward.

The cannonading, which has kept up very briskly during the day, slackens. As the sun goes down behind the lofty Blue Ridge, we march briskly through Frederick City with drums beating and colors flying, then out across a long level tract and as darkness settle down upon the scene, we begin to climb the Blue Ridge [the Catoctin Mountains]. Up, up, four long weary miles when it seems as if I could not take another step. At last we reach the Gap which has been held all day by the enemy.

We see signs of the struggle on each side of the road. Although trapped in darkness, we gain a faint idea of the grand view before us. Signal lights flashing from distant heights and outlines of lofty ranges far away beyond the Potomac. We do not stop but hasten down the mountain side and go into camp near Middletown after a ten mile march. We have marched over seventy miles within a week–a good test for a raw recruit.

1 Response to Voices of the Maryland Campaign: September 13, 1862