Mapping the Attack on Fort Mahone, April 2, 1865

The VI Corps assault on the morning of April 2, 1865 unraveled the Confederate earthworks in Dinwiddie County and forced Robert E. Lee to issue orders to evacuate the lines around Petersburg and Richmond. Their dawn attack that I frequently write about was not alone. It joined a series of other engagements on that decisive day around Petersburg that produced around 9,000 total casualties. Though between a third and a half of that number count Confederates taken prisoner, the 3,936 Federal casualties ranks as one of the twenty bloodiest battles of the war for northern armies.

The VI Corps assault on the morning of April 2, 1865 unraveled the Confederate earthworks in Dinwiddie County and forced Robert E. Lee to issue orders to evacuate the lines around Petersburg and Richmond. Their dawn attack that I frequently write about was not alone. It joined a series of other engagements on that decisive day around Petersburg that produced around 9,000 total casualties. Though between a third and a half of that number count Confederates taken prisoner, the 3,936 Federal casualties ranks as one of the twenty bloodiest battles of the war for northern armies.

Major General John Grubb Parke’s IX Corps suffered nearly half of that number in a daring attack into the teeth of the enemy’s earthworks at Fort Mahone, southeast of Petersburg. Their full day of grinding combat gained the main line of entrenchments but could not crack through the tangled web of secondary Confederate lines to gain entry into the city. Their valiant combat nevertheless locked Maj. Gen. John Brown Gordon’s Confederate Second Corps into a series of attacks and counterattacks throughout April 2nd, preventing Lee from calling upon Gordon for reserves to restore the crumbling Dinwiddie defenses. Immediately after Petersburg fell the next morning, photographers flocked to Parke’s section of the battlefield and produced a number of famous photographs that seem to populate every project featuring the trenches at Petersburg. This is now an attempt to map out Parke’s combat that day.

I should immediately note that I am not the first to cartographically document this overlooked engagement. The noted National Park Service historian Ed Bearss produced a series of five maps that have been digitized in high resolution on Brett Schulte’s incredibly useful research website, The Siege of Petersburg Online. I utilized much of Bearss’s previously conducted research for these maps, tweaking a few troop arrangements. Overall, I cannot admit that these are much more than just a modern rendition providing more clarity for Bearss’s previous work. Julia Steele, David Lowe, and Philip Shiman have also done fantastic work determining the photo shoot locations for many of the iconic images of the Confederate earthworks along the Jerusalem Plank Road for their Petersburg Project.

Like Bearss, I used the Union engineer maps compiled during and after the war by Nathaniel Michler for my basemap. A digitization of one of the best ones for Petersburg’s eastern front can be consulted through the Library of Congress. Michler’s maps are exceptional with only minimal mistakes to be found. The biggest issue I have found with these maps is that they are not perfectly to scale, proving a challenge when trying to overlay them with modern maps. Usually I try to utilize the United States Geological Survey’s historical topographic maps to provide an elevation layer but the first reliable USGS maps for this region are from the 1940s. By this time the conversion of the Jerusalem Plank Road into U.S. Route 301 and the development of a Norfolk & Western Railway line obliterated much of the historic landscape. Since then the city has expanded all the way through the battlefield. Tragically nothing of Fort Mahone or Fort Sedgwick survived development.

I include an aerial image with initial troop movements and an estimation of the earthworks at the end of the article. Exact locations of each battery are certainly open to scrutiny. Fort Mahone was probably located a tad further west and Fort Sedgwick a smidgen more east. Artillery locations are general representation. Further study could perhaps yield more precision.

Most important! Be sure to click on each map for a larger version. Also, please feel free to download and print a PDF file containing all seven phases of the battle here – Battle of Fort Mahone, April 2, 1865.

In lieu of too much contextual background for the final campaign at Petersburg that would once more obscure the battle around Fort Mahone, I’ll simply provide the map below that shows the Union combat and maneuver on April 2nd. Throughout the final campaign, starting March 29th, as the Union Cavalry, II, and V Corps maneuvered through Dinwiddie County to cut Petersburg’s last two supply lines, the VI and IX Corps had standing orders to attack the Confederate entrenchments in their front should they notice any weakening. Indeed, at 4 p.m. on April 1st, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade instructed Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright, commanding the VI, to prepare to attack the next morning. These orders were written just as heavy combat around Five Forks was beginning. When Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant learned of Union victory at that critical intersection, he amended Meade’s orders for an immediate attack all along the lines.

Union subordinates reported the impracticality of an assault that evening so the orders were delayed for early morning, April 2nd. Even then, Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan was unusually timid in his advance north from Five Forks, Maj. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys did not attack with the II Corps south of Hatcher’s Run until mid-morning, and Maj. Gen. Edward O.C. Ord reported that his three Army of the James divisions (nominally under control of Maj. Gen. John Gibbon) north of Hatcher’s Run found the terrain impracticable for an assault. Wright and the VI Corps decisively smashed through the Confederate lines in their front between 4:40 and 5:15 a.m., but Parke had the first jump, launching feints beginning at 4 a.m. against the Confederate lines from the Crater north to the Appomattox River.

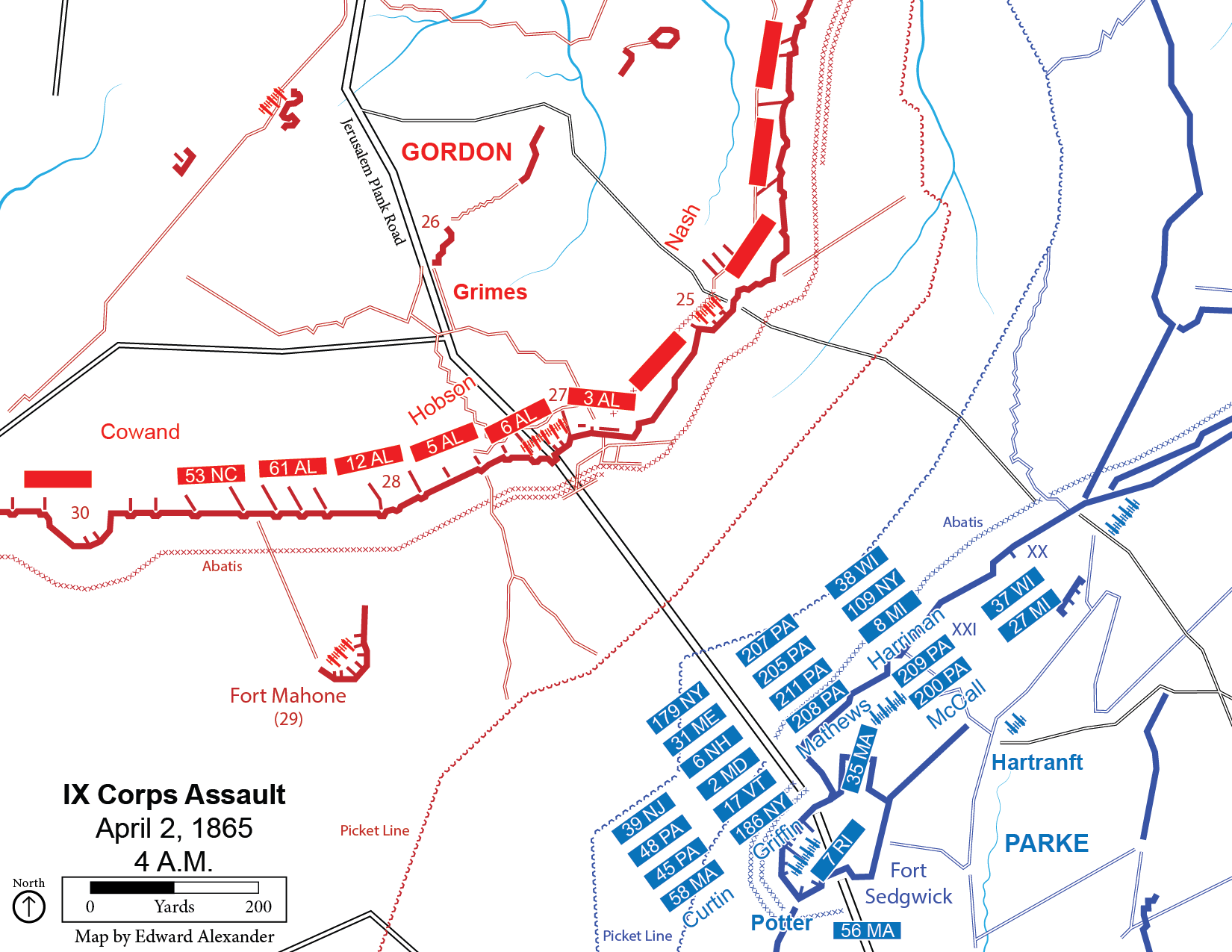

Meanwhile, Parke had formed five brigades from all three of his divisions along the Jerusalem Plank Road, aiming the main thrust of the corps at Batteries 25-30 of the Dimmock Line–Petersburg’s main ring of entrenchments. The next to last in the set, #29 and also known as Fort Mahone, stood several yards in front of the main line while Battery 26 provided a reserve position along the plank road. Secondary lines, additional artillery emplacements, covered ways, and abatis further canvassed the space in front of and behind the Dimmock Line. Confederate pickets meanwhile manned a series of rifle pits several hundred yards further toward the Union lines.

Major General Bryan Grimes’s Confederate division opposed Parke. The 53rd North Carolina garrisoned Fort Mahone to Battery 30 with the rest of Col. David G. Cowand’s brigade stretching further to the west. Colonel Edwin L. Hobson’s Alabamians manned the line left of Fort Mahone past the plank road. There they connected with Col. Edwin A. Nash’s Georgians who faced south and east. Grimes’s final brigade, Brig. Gen. William R. Cox’s North Carolinians meanwhile spread themselves from Cowand’s right west to Battery 45, where the Dimmock Line turned north toward the Appomattox River. Lieutenant General A.P. Hill’s Third Corps meanwhile guarded the extension of the Confederate lines angling off from Battery 45 along the Boydton Plank Road.

Few places along the opposing lines at Petersburg found the adversaries closer to one another than the ground designated for the IX Corps to charge. The soldiers dreaded an assignment in between Fort Mahone (Fort Damnation) and Union Fort Sedgwick (Fort Hell). Parke, however, chose this corridor for his attack, believing the close proximity would allow his men to quickly overwhelm the Confederate Second Corps before they could realize battle had begun, similar to how Gordon had surprised the Federals at Fort Stedman eight days earlier. This time Parke intended to properly exploit any breakthrough.

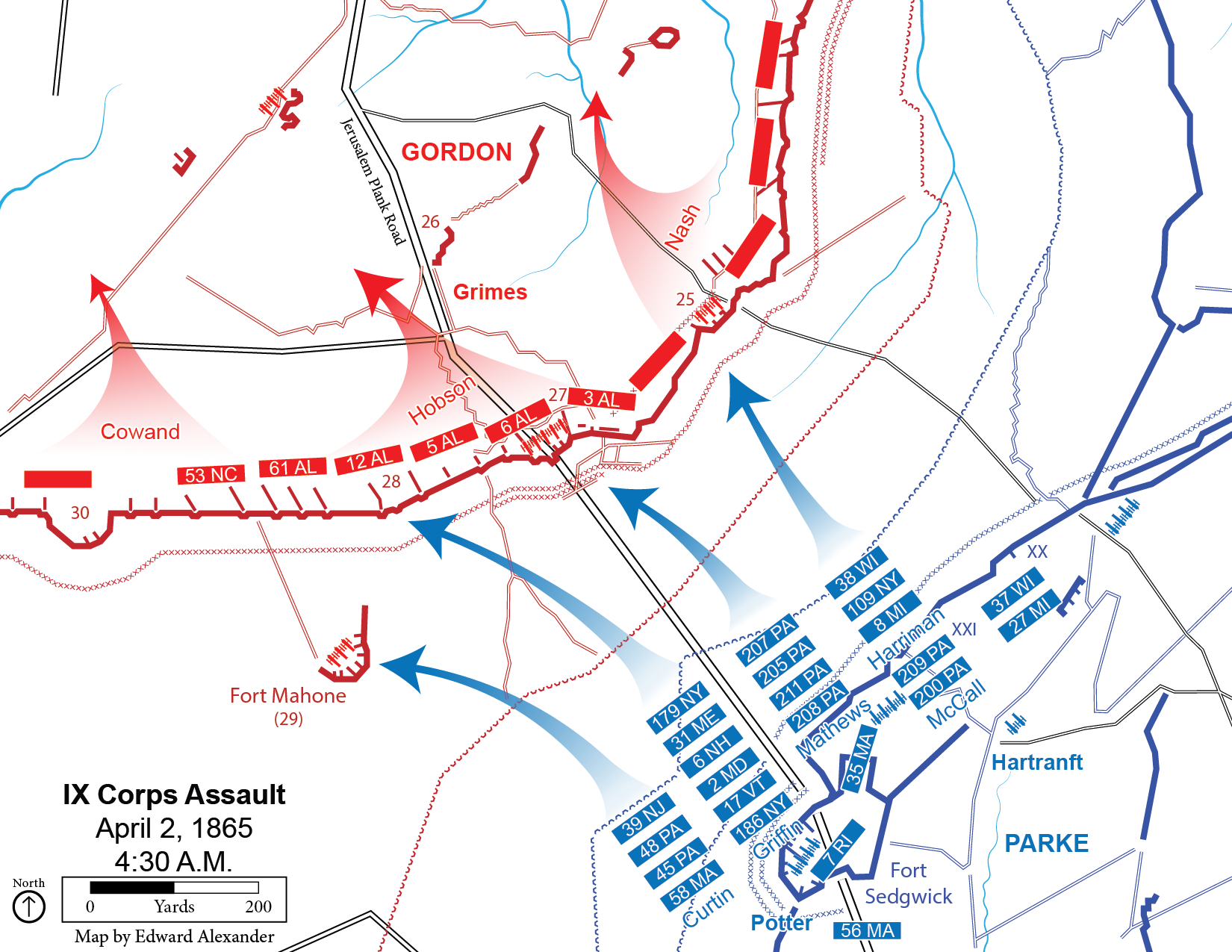

He placed Brig. Gen. Robert B. Potter’s 2nd Division west of the plank road. Brigadier General Simon G. Griffin arranged six of his 1st Brigade’s regiments in a column in front of Fort Sedgwick while four of Col. John I. Curtin’s 2nd Brigade regiments supported them on the left. Brigadier General John F. Hartranft formed to the right of Potter. Colonel Joseph A. Mathews placed his three regiments east of the road, borrowing the 208th Pennsylvania as support. Lieutenant Colonel William H.H. McCall’s other two regiments provided a reserve force along the Union earthworks. Colonel Samuel Harriman formed three regiments in column to the right of Mathews, with an additional two alongside McCall.

Griffin instructed three companies of skirmishers to seize the Confederate rifle pits once the signal gun fired. Meanwhile pioneers would clear the obstructions in front of the earthworks allowing Griffin to charge Battery 28 while Mathews attacked Battery 27. Once those were seized Curtin would advance on Fort Mahone to the left and Harriman would attack Battery 25 on the right.

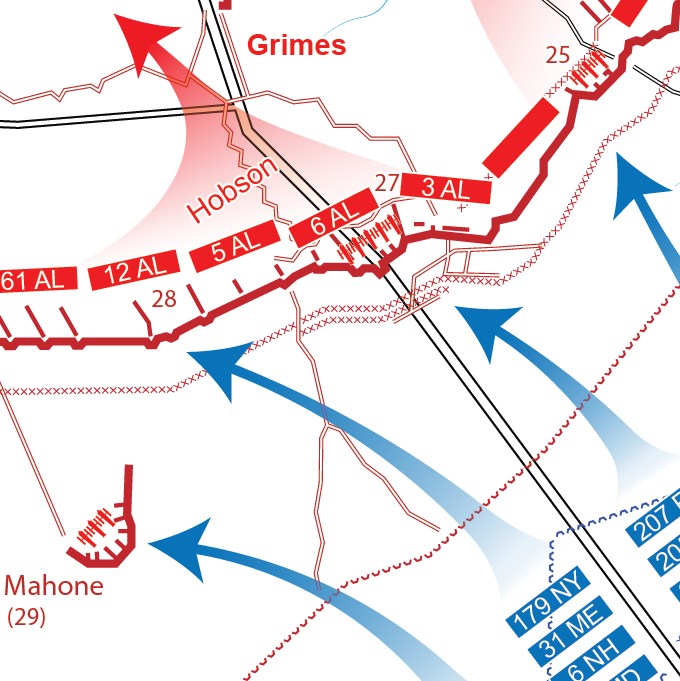

The signal gun’s discharge at 4:30 spurred the IX Corps forward. Griffin and Mathews quickly overran the Confederate rifle pits and squeezed through the gaps cut in the abatis by the pioneers. After a brief struggle up the parapet the two brigades piled into the entrenchments on either side of the Jerusalem Plank Road, driving back the Alabamians until they rallied at Battery 26. Harriman’s brigade meanwhile forced their way into Battery 25 where, with assistance from gunners of the 1st Connecticut Heavy artillery, they turned the Confederate cannon against their former garrison. Curtin’s brigade also pressed forward at this time, capturing Fort Mahone and slowly picking their way toward the main Confederate line.

The signal gun’s discharge at 4:30 spurred the IX Corps forward. Griffin and Mathews quickly overran the Confederate rifle pits and squeezed through the gaps cut in the abatis by the pioneers. After a brief struggle up the parapet the two brigades piled into the entrenchments on either side of the Jerusalem Plank Road, driving back the Alabamians until they rallied at Battery 26. Harriman’s brigade meanwhile forced their way into Battery 25 where, with assistance from gunners of the 1st Connecticut Heavy artillery, they turned the Confederate cannon against their former garrison. Curtin’s brigade also pressed forward at this time, capturing Fort Mahone and slowly picking their way toward the main Confederate line.

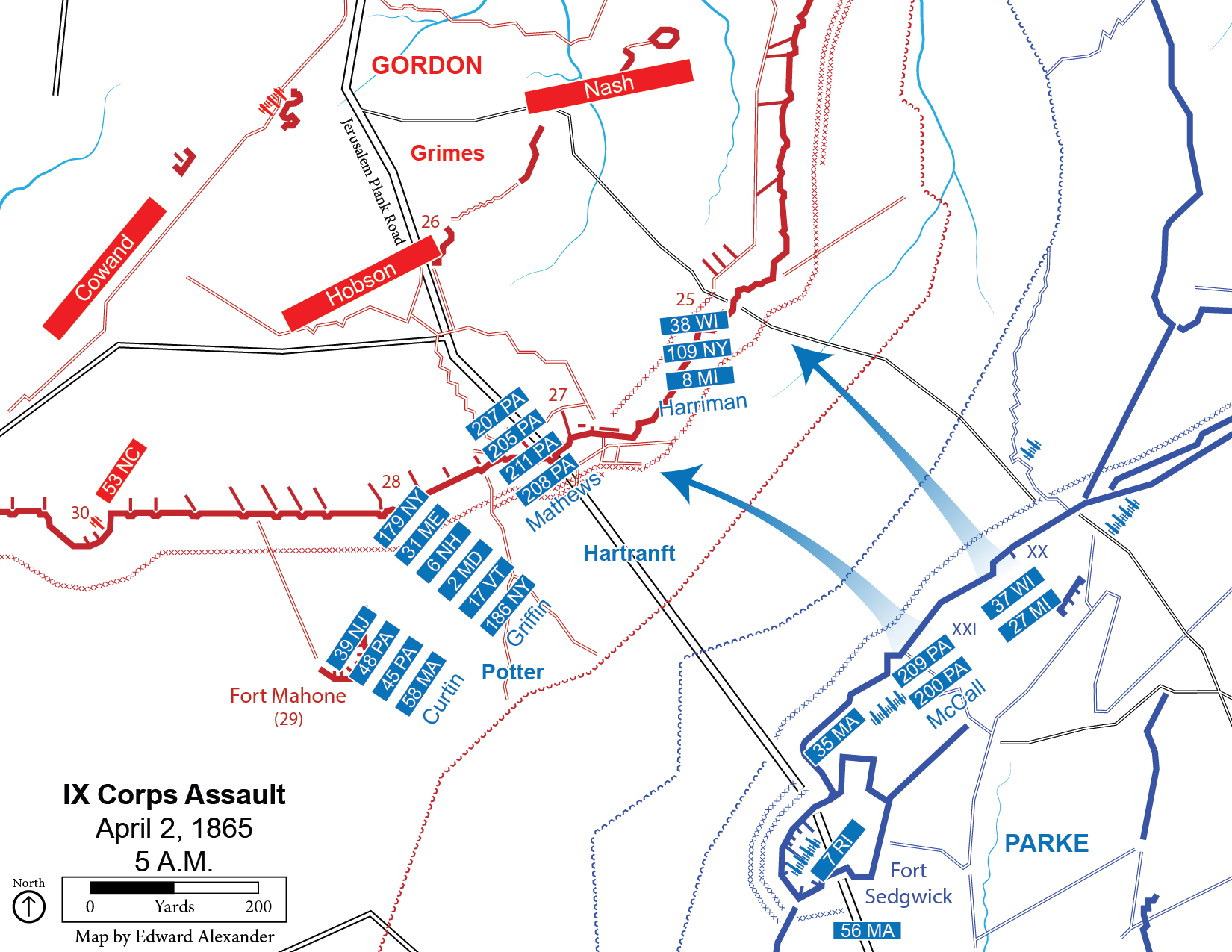

While Grimes frantically sought to establish a new position to contain Parke’s advance, the IX Corps reserve moved forward to secure what their comrades had gained. Heavy casualties in the initial attacks, including the death of Col. George W. Gowan, commanding the 48th Pennsylvania, and a serious wound to Potter, further grounded any further forward movement west of the plank road. Command of the 2nd Division devolved onto Griffin while Col. Walter Harriman, future New Hampshire governor, took charge of the 2nd Brigade. Griffin refused Curtin’s brigade, the Federal left flank aligning themselves along the spur of Confederate earthworks running south to Fort Mahone.

While Grimes frantically sought to establish a new position to contain Parke’s advance, the IX Corps reserve moved forward to secure what their comrades had gained. Heavy casualties in the initial attacks, including the death of Col. George W. Gowan, commanding the 48th Pennsylvania, and a serious wound to Potter, further grounded any further forward movement west of the plank road. Command of the 2nd Division devolved onto Griffin while Col. Walter Harriman, future New Hampshire governor, took charge of the 2nd Brigade. Griffin refused Curtin’s brigade, the Federal left flank aligning themselves along the spur of Confederate earthworks running south to Fort Mahone.

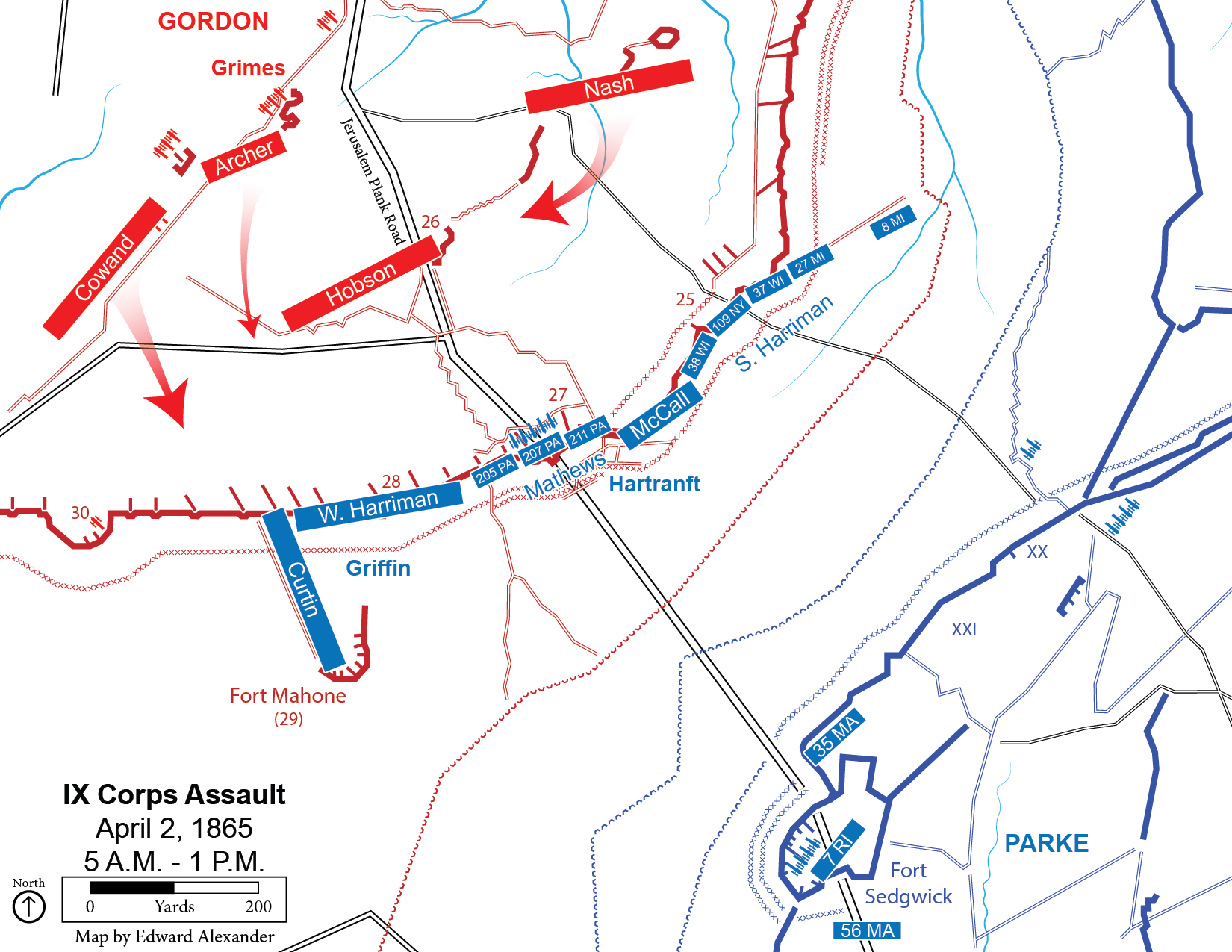

Cowand rallied his brigade and prevented Union expansion of their breakthrough into Battery 30. Lieutenant Colonel Fletcher H. Archer meanwhile hustled his two battalions of Virginia Reserves into position to assist the North Carolinians. Grimes also directed artillery to plunge their fire into the Confederates’ lost entrenchments. He tried several times to spur his men forward to regain the Dimmock Line but failed to budge the Union forces, who now clung to their captured works with grim determination. Parke wired for assistance but Grimes ferociously struck before any could arrive.

Cowand rallied his brigade and prevented Union expansion of their breakthrough into Battery 30. Lieutenant Colonel Fletcher H. Archer meanwhile hustled his two battalions of Virginia Reserves into position to assist the North Carolinians. Grimes also directed artillery to plunge their fire into the Confederates’ lost entrenchments. He tried several times to spur his men forward to regain the Dimmock Line but failed to budge the Union forces, who now clung to their captured works with grim determination. Parke wired for assistance but Grimes ferociously struck before any could arrive.

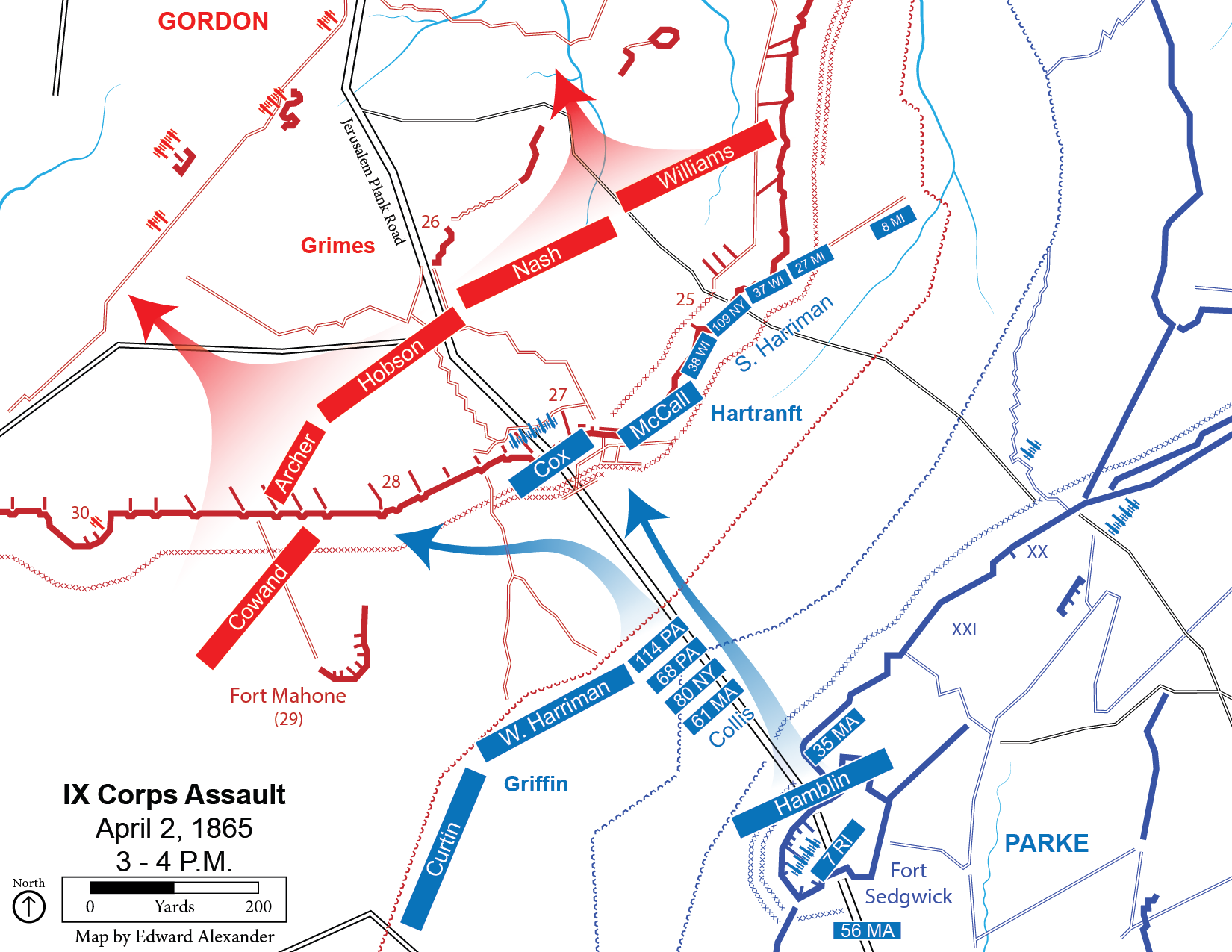

A Confederate counterattack at 1 P.M. failed to dislodge Parke’s men but he returned two hours later just before the IX Corps received their reinforcements. Colonel Charles H.T. Collis’s Independent Brigade hurried south from their position at Meade’s Station, on the U.S. Military Railroad, to Fort Sedgwick. Wright meanwhile sent Col. Joseph Eldridge Hamblin’s VI Corps brigade east. Grimes’s 3 P.M. assault hit while Collis and Hamblin moved forward on the plank road. Small bands of North Carolinians flanked the left of Curtin’s line in Fort Mahone while Archer, Hobson, and Nash attacked south. Grimes may have also received assistance in the form of Col. Titus V. Williams’s consolidated Virginia brigade. Griffin stubbornly withdrew his division, contesting every traverse, parapet, and ditch. Hartranft’s division and Harriman’s brigade, with no force threatening their flank, managed to stick to their position, limiting Grimes’s gains.

A Confederate counterattack at 1 P.M. failed to dislodge Parke’s men but he returned two hours later just before the IX Corps received their reinforcements. Colonel Charles H.T. Collis’s Independent Brigade hurried south from their position at Meade’s Station, on the U.S. Military Railroad, to Fort Sedgwick. Wright meanwhile sent Col. Joseph Eldridge Hamblin’s VI Corps brigade east. Grimes’s 3 P.M. assault hit while Collis and Hamblin moved forward on the plank road. Small bands of North Carolinians flanked the left of Curtin’s line in Fort Mahone while Archer, Hobson, and Nash attacked south. Grimes may have also received assistance in the form of Col. Titus V. Williams’s consolidated Virginia brigade. Griffin stubbornly withdrew his division, contesting every traverse, parapet, and ditch. Hartranft’s division and Harriman’s brigade, with no force threatening their flank, managed to stick to their position, limiting Grimes’s gains.

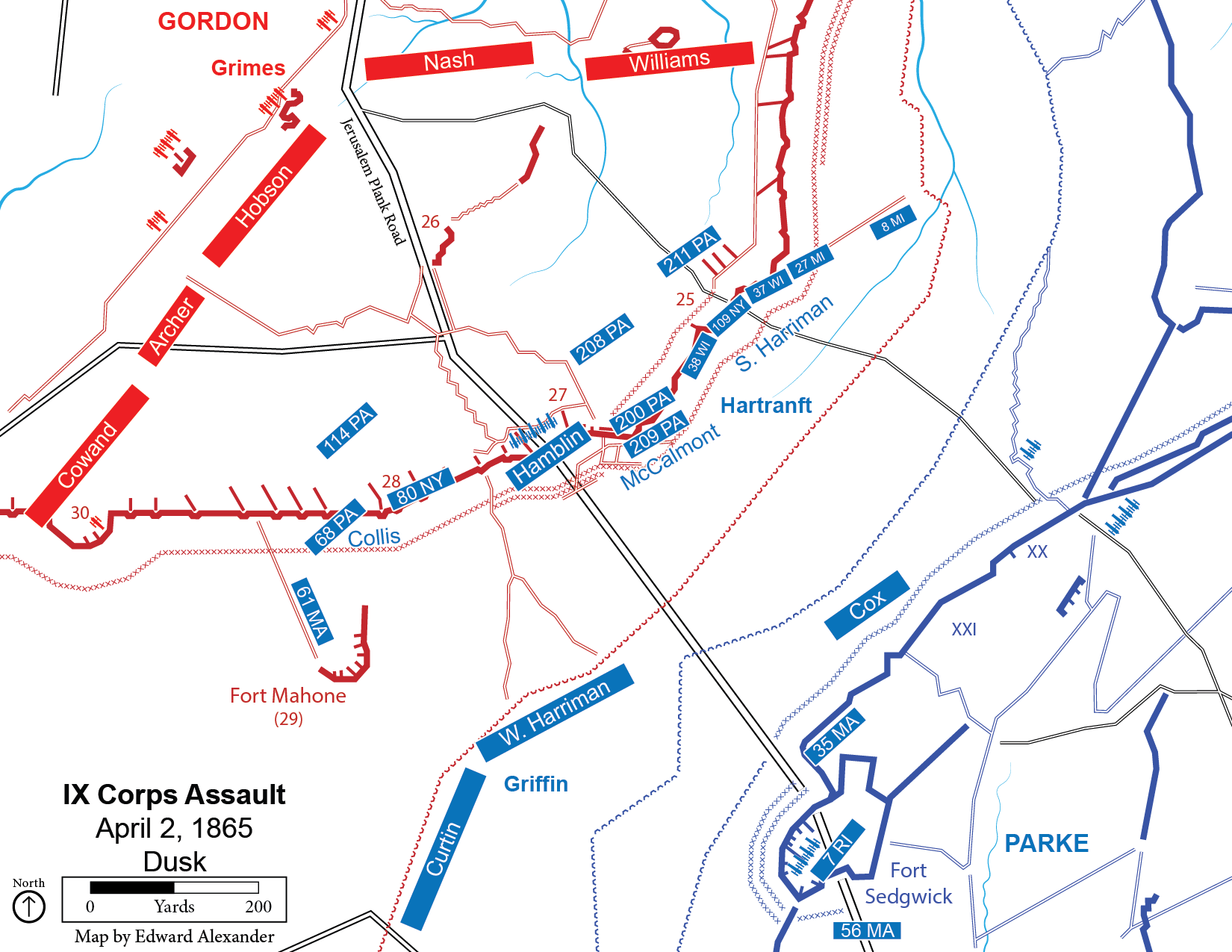

Collis’s brigade counterattacked around 3:30, forcing the Confederates out of Batteries 28 and 29 once more. Hamblin also moved forward to strengthen the Union position at Battery 27. Colonel Robert C. Cox meanwhile took command of the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, Mathews having been sent to the rear on account of illness. Despite his subordinates’ request to follow up their success with an attack on Gordon’s secondary lines, Parke demurred, believing that even heavier casualties could not justify future assaults. By this time, the Confederates in Dinwiddie had yielded their positions at Sutherland Station, Fort Gregg, and Edge Hill. Lee scraped together a new line sealing Petersburg’s western front from Battery 45 to 55 but the Confederate commander was already focusing on how to evacuate his men from Petersburg and Richmond.

Darkness fell with the IX Corps in possession of all of the entrenchments they had captured throughout the day’s fight. Grimes’s energy and the willingness of his Confederate infantrymen to continuously throw themselves into the breach staved off immediate capture of Petersburg on the 2nd. After the sun set they slowly began withdrawing into the city, where they crossed the Appomattox River on the Campbell, Pocahontas, and railroad bridges, beginning the week-long retreat to Appomattox Court House. Cautious Federals crept up to the vacant inner lines before sunrise on April 3rd. Once discovering they had been evacuated, the northern soldiers raced with their comrades east and west of Petersburg to be the first to enter a city that had defiantly stood within artillery range since June 1864.

Darkness fell with the IX Corps in possession of all of the entrenchments they had captured throughout the day’s fight. Grimes’s energy and the willingness of his Confederate infantrymen to continuously throw themselves into the breach staved off immediate capture of Petersburg on the 2nd. After the sun set they slowly began withdrawing into the city, where they crossed the Appomattox River on the Campbell, Pocahontas, and railroad bridges, beginning the week-long retreat to Appomattox Court House. Cautious Federals crept up to the vacant inner lines before sunrise on April 3rd. Once discovering they had been evacuated, the northern soldiers raced with their comrades east and west of Petersburg to be the first to enter a city that had defiantly stood within artillery range since June 1864.

Parke reported 18 officers and 235 enlisted men killed, 85 officers and 1,220 men wounded, and 5 officers and 156 men missing on April 2nd, totaling 1,719 casualties. Potter’s division suffered the most and though the wounded brigadier survived his severe wound it is believed it contributed to his early death in 1887 at the age of 57. The IX Corps captured at least 1,000 Confederates during the day. Precise numbers of killed and wounded would be impossible to determine for Gordon’s corps.

Though their attack did not directly force Lee’s hand in evacuating Petersburg, the IX Corps had every reason to be proud of their accomplishments on that decisive day. They attacked Confederate earthworks designed to allow the defense in depth utilized by Grimes to limit the breakthrough. On the other side of the city, only one line of earthworks stretched to the southwest where Wright had attacked more successfully. While Parke has also been criticized for targeting one of the strongest portions of the Confederate line for his main assault, this is no worse than Maj. Gen. John Gibbon’s commitment to attack, rather than flank or simply ignore, Fort Gregg. This decision cost the Army of the James 714 casualties. The IX Corps’ attack at least had the benefit of darkness. Parke certainly acted with more energy and initiative that day than many of his colleagues, particularly the sluggish Sheridan who hardly followed up his victory from the previous day.

Perhaps the IX Corps reputation–a stigma of their association with the beleaguered Ambrose Burnside and their time spent away from the Army of the Potomac–contributed to the overlooking of their actions on April 2nd. While Parke’s veterans themselves praised their gallant deeds, the battle has been largely ignored in both the historical and modern day. Confederate veterans meanwhile wrote little about the final attacks against Petersburg. When they did write, they latched onto Fort Gregg to demonstrate southern gallantry against overwhelming numbers.

Two monuments crown the battlefield, though they probably should switch locations. In 1907 a statue of the slain Col. Gowan was erected along the Jerusalem Plank Road. Today it stands near the intersection of Crater Road (U.S. 301) and Sycamore Road (Alt. U.S. 301). Gowan was killed while Curtin’s brigade angled for Fort Mahone. Just south of the fort’s former location, a monument to Hartranft’s Pennsylvania division was dedicated in 1909. A Virginia Civil War Trails wayside exhibit notes that Abraham Lincoln’s visit to the battlefield the day after the combat.

Nothing exists of Fort Mahone, the other Confederate batteries in line, nor Fort Sedgwick. If you’re properly looking at the right angle from the Hartranft monument you can catch a glimpse of the roof of the building standing on Sedgwick’s site. An attempt to overlay this lost battlefield onto a modern aerial photograph concludes this mapping activity. Hopefully it helps prevent the actions of those who fought here from continuing to be lost as well.

Enjoyable article.

I’m grateful for your attention to the IX Corps and John Parke. It seems to me that both unit and commander have been ignored by CW historians. I am interested in the record of both; almost always in supporting roles, the corps between western and eastern theaters and Parke shuttled between roles as Commanding General or Chief of Staff of the IX Corps. Not glamorous and often unfortunate, they deserve to be remembered for more than the Burnside bridge and the Crater.

Really cool cartography–and great use of the maps to illustrate the story!

Knocked it out of the park, Ed. Nicely done.

Excellent work.

Very good—I especially love the troop overlays on modern road networks.

The cartography is amazing, it brings such a definitive clear answer concerning who was where in the understudied role of the ix Corps. Great job!!!

With more Petersburg books due out in the next year does anyone know of a cartography atlas such as “The battle of Gettysburg in Maps” or anything similar? At least we know we have the ix Corps thanks to Mr. Alexander!!! Would be a great SavasBeatie book-

Dear mr. Alexander I am working on my first book that hopefully will be published bye a great company like savasbeattie if I’m lucky. I am writing and a very basic battle because I am starting out new. I did get my b. A. At Michigan but it’s not nearly enough education for what I’m tackling. I just wanted to say if I can get someone to draw the few Maps I need half as good as yours I will be blown away. Your maps are a thing of beauty and they make me want to delve into the reading great great job, great hard work great talent keep it up sir.

The reason your Maps Blow Me Away I always had a dream to write a book and have it published. Unfortunately life threw me a curveball and my last tour didn’t go as planned and I’m on mental and physical disability ( seizures and new knees). I went through the pity feel sorry for myself and then angry at the world stages but now I accept what happened and I’m very happy with my life and I love my family but it was always a dream when I was younger to write a book and get it published and I still think I can do it hopefully. But in the time I was gone computer graphics and Design are so Advanced when they’re in the hands of someone as talented as you it just blows me away it’s so clear and so easy to follow the battle so again I just want to say I really appreciate the article and the whole thing really inspires me to work that much harder on my book so thank you for the inspiration sir and keep kicking but my man

7th Rhode island Regiment was stationed in Fort Hell and took part in the assault on Fort Damnation April 1865 interestingly in Regimental history is a picture of a Picket Post in front of Ft Mahone and the same sight in October 1892! see between pp.280-281 of their Regimental History:

https://books.google.com/books?id=eml9U2RZArQC&pg=PA257&dq=rhode+island+regiment+and+Fort+Mahone+1865&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwja-oitk9TZAhVHTd8KHT6dCegQ6AEIJzAA#v=onepage&q=rhode%20island%20regiment%20and%20Fort%20Mahone%201865&f=false

Note: Only mistake is calling this a Union Picket Post..in fact it is CS [See Frassanito Grant and Lee the Virginia Campaigns….Hope this is helpful

the picket post was Union!

http://www.petersburgproject.org/the-rebel-in-the-road.html

at last//the location of some of the pictures…Ft Mahone….

https://civilwartalk.com/threads/site-of-ft-mahone-petersburg-1865.86204/

Then and now Petersburg April 1865

http://www.petersburgproject.org/fort-mahone-cs-batteries-25–27.html

Beautiful maps and an excellent discussion of an under-reported battle (although, graphically it is reported- there are photos),

http://www.petersburgproject.org/fort-mahone-cs-batteries-25–27.html, http://www.petersburgproject.org/the-rebel-in-the-road.html; and

drawings, http://www.petersburgproject.org/rives-salient-fort-mahone.html.

Also, the large CSA Columbiad battery still exists;

http://www.petersburgproject.org/fieldwork—-petersburg.html

As for what everybody else says on here…..Ditto! Well done..

Blog on Bollingbrook Street Petersburg damage 1865

https://spotsylvaniacw.blogspot.com/2014/03/petersburg-siege-look-at-bollingbrook.html

Now I understand why the site of Ft Mahone is gone…a parking lot….!

One wonders why the pictures of Batteries 25 and Batters 27 were marked as Ft Mahone….sale appeal perhaps….???? Could it be earth formations nicknamed Fort H*ll and Fort D********* had more appeal then Rives Salient? Also regarding the Rebel in the Road…in Frassanito Grant and Lee he speculates the dead CS Soldier with blood running out his nose…could have been lying just across from the Rebel [in the Road] picture….perhaps a Shell burst was the cause of his demise as well….but I’ll let the experts debate that!

Here is link to second Rebel [in the road[?] picture….that structure in background part of Ft Sedgwick?

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dead_soldier_(American_Civil_War_-_Siege_of_Petersburg,_April_1_1865).jpg

There is an interesting Civil War Website forum at https://www.civilwartalk.com/

I cant link on this website myself..but can someone please link this site to that website?

Also there is the possibily of a third Rebel in the Road picture link see Frassanito Grant and Lee VII-12 picture [top of page] I’ve corresponded with Frassanito who reports the defense line in the background is the same as p.363 [aka Dead Rebel in the Road]

https://www.loc.gov/item/2012647828/

there was another online version that showed the background more extensive showing the same time of wooden barracedes as in “Rebel in the Road”

Picket Post {in front of Ft Mahone[?}

https://www.loc.gov/item/2004660064/

I read elsewhere Seymour’s 3rd Division of VI Corps was sent post break through to reinforce Park in the afternoon of April 2. I’m curious as to their positioning and movements in this battle.

After breaking through the Confederate lines near the Hart house, Seymour’s division swung southwest and captured Fort Alexander. They continued into Fort Davis before forced out by McComb’s Tennesseans counterattack. Portions of Getty’s division then overlapped Fort Davis, forcing McComb’s retreat and Seymour and Getty continued rolling the Confederate line down to Hatcher’s Run.

After securing Hatcher’s Run and the length of the Boydton Plank Road, the Sixth Corps turned north toward Petersburg’s inner defenses. Two divisions from John Gibbon’s Twenty-fourth Corps replaced them at the head of the advance, so Getty moved west to take position opposite R.E. Lee’s headquarters at Edge Hill while Seymour moved into reserve behind the Twenty-fourth Corps as they arranged themselves for the attack on Fort Gregg.

Parts of the division may have gone further east to support Parke but it doesn’t look like any participated in the fighting around Fort Mahone. Colonel William S. Truex reported he countermarched his “brigade in the direction of Petersburg, at the Brick Chimneys in front of Petersburg, and on the extreme left of the Ninth Corps.” Lieutenant Colonel George B. Damon reported the 10th Vermont “was placed in position on the right of the brigade, my right resting on the Vaughan road.”

My Great Grandfather of the 205th PA was wounded in this action. Thank you for FINALLY recognizing that it happened!

Edward. ;let me look at your bibliography please.

Bryce

This battle was fought on my cousin’s farm, Timothy Rives (1807 – 1865). This property may have been the original settlement of our shared great grandfather, Timothy Rives Jr (1625 – 1692). We know Timothy Rives Jr settled near Blandford Va. He was the first Ryves – Rives emigrant to arrive in America from Oxford, England, where he fled the English Civil War for safe haven in Virginia. I’ve been studying my Ryves/Rives/Reaves ancestry since 2016. I’ve learned much and it’s answered several questions about myself.

Thanks for sharing, I’ll add that note on the Rives family to my Ft Mahone file.

And it’s good to see (by the current spelling of your family name), that I appear to have been pronouncing it properly this whole time!

Philip Shiman of the Petersburg Project thinks the soldiers were north carolinians from Cowan’s brigade. He has mapped the route the photographer took.

Was Ft Mahone on what is now Ft Mahone Street? I found what I believe was Battery 26 on Timothy Rives farm. I’m returning in January-Feb 2021

Hi,

Have you read the book by William Glenn Robertson and recently updated and reprinted, The Battle of the Old Men and Young Boys? I believe part of this June 9th action also occurred on your ancestor’s land.

bryce

I recently purchased and have begun reading it. I visited the area last week, knocking on doors, talking to those home. I found what I believe is Battery 26 in some woods behind what I believe may have been the location of Rives Family Cemetery on Timothy Rives farm. I couldn’t locate physical earthen remnants of Battery 25, located at the home of Timothy Rives home, but a neighbor pointed out where she understood a earthen trench was years and years ago. Given that lead, I believe I know the current address of where Tmothy Rives home was just off E South Blvd and N Westchester Dr. Battery 25 would be on Colston St

When I visited there last week, my dousing rods located countless males buried in the backyard of a private residence, yards away from Battery 26. In his front yard, my dousing rods picked up several female burials which suggests that area marked a family cemetery, maybe the Rives Family Cemetery. The owner was familiar with some battle history because he noted years ago, civil war historians and collectors received permission to scan his property for relics of which they found many.

GGGrandon of 38th WI soldier John B. Coyhis KIA 4/2/1865 here. Went to Petersburg (and Poplar Grove cemetery) 15 years ago, and couldn’t really get a feel for the geography of the battlefield, now I am able to return with much more purpose. Thank you so much for the incredible details!

My ggg grandfather was there with Patterson’s confederate battery across the Jerusalem plank road. Thank you.

A really great piece. Was able to use it to show someone the location and specifics of their ancestor’s demise, mentioned in an unpublished source. One note though. The tasking shown for the 2nd Maryland Infantry was what was planned, but the facts on the ground were a bit different – as the attack began, the 2nd moved toward their assigned objective, but began to get bunched up in a trench. Seeing this, those in back, shifted to the left, spending the rest of the day with Curtin’s troops, while the rest moved as assigned. It is a strange experience to know such specific and arcane details of an event so long ago thanks to a participant – Col. Benjamin F. Taylor, 2nd Maryland Infantry, US.