Fortress Washington, Part II

Emerging Civil War welcomes back guest author Steve T. Phan to continue his discussion of Fortress Washington. You can find his first post here.

In the late afternoon of July 21, 1861, Captain Barton S. Alexander, U.S. Army Engineers, described the Union Army of Northeastern Virginia’s fight along banks of Bull Run in a message to the War Department in Washington D.C. The future chief engineer of the Department of Washington’s communique was concise and alarming:

General McDowell’s army in full retreat through Centreville. The day is lost. Save Washington and the remnants of this army. All available troops ought to be thrown forward in one body. General McDowell is doing all he can to cover the retreat. Colonel (Dixon S.) Miles is forming for that purpose. He was in reserve at Centreville. The routed troops will not reform.[1]

The disquieting report stirred the War Department into action. Ever the stalwart, Lieutenant General Winfield Scott responded to the Federal defeat with the steadiness and bearing expected of a fifty-year military veteran. He dispatched reinforcements to the front and called upon support in the immediate region, notably Baltimore, the Shenandoah Valley, and Pennsylvania. When Brigadier General Irvin McDowell informed Scott that he intended to make a stand with the remnants of his army near Centreville, Scott supported with reinforcements from Alexandria. McDowell’s stand was short. The beleaguered field commander, advised by the commanding general to “return to the line of the Potomac,” moved the army ingloriously back to the confines of the city.[2] Despite the serious threat of a Confederate incursion, the Union infantry continued to comprise the frontline defenses of the capital but not for long. The die had been cast before McDowell’s army on Henry House Hill.

Prior to their fight along the banks of Bull Run Creek, McDowell’s raw soldiers initiated the construction of fortifications after crossing the Potomac south into Virginia in late May and early June 1861. Following the bombardment Fort Sumter and subsequent call for volunteers to suppress the rebellion, the War Department strained to shift the war machine into full motion. The timely arrival of reinforcements, both regular and volunteer regiments, secured the capital.

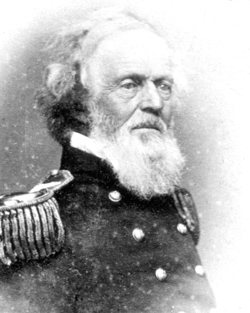

General Scott then looked to his native state before issuing his next decree. Virginia’s protracted debate over adopting an ordnance of secession delayed any concerted forward movement by the US Army. Scott nonetheless prepared for the worst. He ordered a reconnaissance of the ground directly around the city in preparations for an advance. The task fell to the Department of Washington’s commander, Colonel Joseph K. Mansfield.

A grizzled old army veteran of nearly forty years, Mansfield took command of the department in the final days of April 1861. In his May 3 report to the general-in-chief, Mansfield dutifully noted that the ground east of Washington overseeing the Naval Yard across the Eastern Branch (Anacostia River) “can readily be fortified at any time by a system of redoubts encircling the city.”[3] He was confident ample troops in the city could be directed in that direction.

The issue, Mansfield contended, was the direct threat to Washington (Georgetown and the Federal city) from the Virginia shoreline. The heart of the government—the White House, Capital building, departments, arsenal, and aqueduct—was a mere “two and a half miles across the river from Arlington high ground, where a battery of bombs and heavy guns, if established, could destroy the city with comparatively a small force after destroying the bridges.”[4] In order to prevent the city’s “bombardment at the will of an enemy,”[5] Mansfield proposed that the army seize the initiative. He recommended “that the heights above mentioned be seized and secured by at least two strong redoubts, one commanding Long Bridge and the other the Aqueduct Bridge, and that a body of men be there encamped to sustain the redoubts and give battle to the enemy if necessary.”[6]

The soon-to-be brigadier general realized such a move might “create much excitement in Virginia,” but there could be no greater cause of tension than an enemy occupation and bombardment of Washington across the Potomac.[7] Mansfield ended the report by informing Scott that his engineers, most notably his chief, Major John G. Barnard, were “maturing plans and reconnoitering further.”[8] The department commander consulted heavily with Barnard, whose services were critical to the development of the Defenses of Washington in the coming weeks.

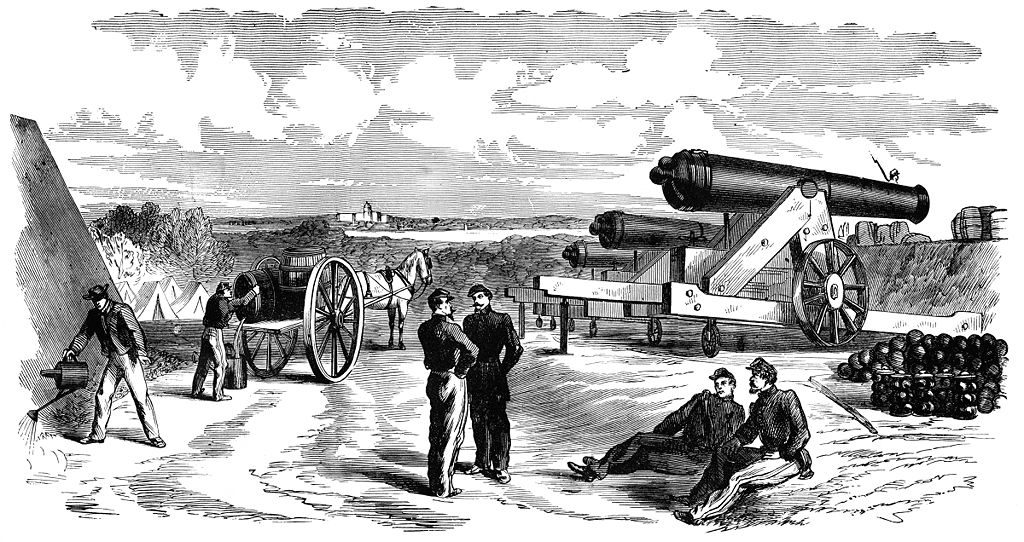

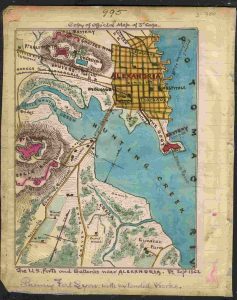

The army moved swiftly after Virginia’s vote for secession on 23 May 1861. The next day, General McDowell’s forces crossed the Potomac and occupied Arlington Heights and Alexandria to the south without a fight. McDowell assumed formal command of occupational forces in Alexandria four days after its fall. He reported to headquarters that, despite “a want of tools” and transportation to move troops at the Alexandria wharf to the hills overlooking the city, “defensive works [were] under construction.”[9]

The hills were fortified to secure the army’s occupation of the city. The army also begun erecting two major forts. The first “main work cover[ed] the Aqueduct and ferry opposite Georgetown,” which “was in a fair state,” stated McDowell.[10] Soldiers of the famed 69th New York Infantry constructed the strategic work that protected both Aqueduct Bridge and Mason’s Island (present day Theodore Roosevelt Island). As common practice, the men named the fort in honor of their commander, Colonel Michael Corcoran.

To the southeast, Federal troops constructed the largest defensive earthwork in the Defenses of Washington: Fort Runyon. Brigadier General Theodore Runyon of the New Jersey militia commanded a division in McDowell’s army, and his men wasted no time breaking ground on the fort. Once fully completed, Runyon’s pentagonal perimeter measured 1,500 yards, mounted 21 guns, and was garrisoned by nearly 2,000 men. It strategically guarded the south approach to Long Bridge, directly linked to the Federal city, and was positioned at the Columbia Pike and Alexandria Pike crossroads.

More works were added to complement the original two: Fort Ellsworth due west of Alexandria and Fort Albany, built to protect Runyon’s vulnerable flank along the Columbia Pike. These foundational sites were erected to secure Federal presence in Northern Virginia, providing a springboard for the army’s offensive operations against Confederate forces reported to be operating to the southeast. If necessary, they provided a fallback and rallying point if McDowell’s Army of Northeastern Virginia happened to be driven back to the gates of Washington. Following the army’s ill-fated baptism of fire at Manassas two months later, soldiers converted these temporary positions into permanent, fortified structures.

The preliminary Defenses of Washington provided a formidable fall back and concentration point for McDowell’s dispirited army. Upon hearing disastrous reports of the army’s defeat, headquarters ordered General Mansfield at 2:30 am on July 22 to “man all the forts and prevent soldiers from passing over to the city” to prevent widespread panic.[11] The high command believed Mansfield “need[ed] every man in the forts to save the city.”[12] Their sentiment was well-placed.

Colonel William T. Sherman reported to headquarters later that morning that the army suffered “a terrible defeat and has degenerated into an armed mob.”[13] To reform the broken command, he proposed “to strengthen the garrisons of Fort Corcoran, Fort Bennett, the redoubt on Arlington road, and the block-houses.” The brigade commander was supported by McDowell, who formally requested further reinforcements to maintain his position south of the Potomac. Three artillery companies of Regulars manned earthworks while additional troops were needed to garrison Fort Corcoran.

General Scott responded to his commanders’ requests accordingly. He called upon the reserve division at Alexandria under Runyon to enhance the defenses, with instructions to consult engineers and “strengthen the garrisons of Forts Ellsworth, Runyon, and Albany.”[14] Another fifteen infantry regiments accompanied by artillery attachments were directed across the river. The general-in-chief then ordered a general withdrawal of “all the remaining troops and all the wagons and teams not absolutely needed”[15] by McDowell to the army’s camps around Washington, “protected by the forts.”[16] The army’s resolute determination to secure the capital after the battle appeared to have stymied any serious threat from the victorious enemy. Simon Cameron was convinced. On the same day of Sherman’s grim report, the Secretary of War declared to Republican colleagues that the “works on the south bank of Potomac are impregnable, being well manned with re-enforcements. The capital is safe.”[17]

General Scott was confident of the city’s safety but needed assistance to reinvigorate the army. Lorenzo Thomas, Adjutant-General U.S. Army, carried orders for Major General George B. McClellan one day after Manassas that circumstances in Washington made his “presence necessary.”[18] The rising star, fresh from victories in western Virginia, dutifully turned over command of his forces and proceeded directly to his new station. On July 25, McClellan assumed formal command of “Division of the Potomac, comprising the Military Department of Washington and Northeastern Virginia. Headquarters for the present at Washington.”[19] The young general’s ascendance marked a momentous transformation in the evolution of the Defenses of Washington. McClellan’s guidance determined the shape of Fortress Washington and other critical defenses of the capital.

Steve T. Phan is a historian and park ranger for the National Park Service (Civil War Defenses of Washington). He received his MA in history at Middle Tennessee State University, BA in history at the University of Northern Colorado and participated in the Gettysburg Semester at Gettysburg College.

Sources:

[1] The War of The Rebellion: Original Records of the Civil War (Columbus: Ohio State University); digitized from original, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (70 vols. in 128 parts; Washington, 1880–1901), Serial 002, Chapter IX, 747, accessed https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records; hereinafter cited as Official Records.

[2] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 747.

[3] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 618.

[4] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 618-19.

[5] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 619.

[6] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 619.

[7] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 619.

[8] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 619.

[9] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 653.

[10] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 653.

[11] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 754-55.

[12] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 755.

[13] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 755.

[14] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 753.

[15] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 755.

[16] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 754.

[17] Official Records, Serial 002, Chapter IX, 756.