Watching the “Merrimac”

One of the joys of a historian is finding that perfect eye-witness account of momentous events, one that puts you alongside our ancestors and sees through their eyes. The following is just such a viewpoint.

“IN March, 1862, I was in command of a Confederate brigade and of a district on the south side of the James River, embracing all the river forts and batteries down to the mouth of Nansemond River,” wrote Brigadier General R. E. Colston. “About 1 p. m. on the 8th of March, a courier dashed up to my headquarters with this brief dispatch: ‘The Virginia is coming up the river.’ Mounting at once, it took me but a very short time to gallop twelve miles down to Ragged Island.”[1]

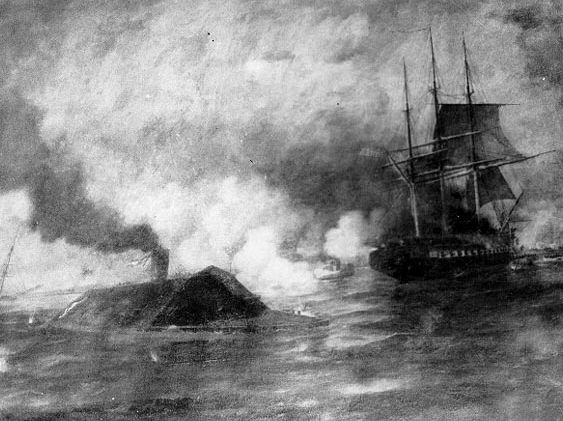

From the south shore of Hampton Roads, General Colston watched all day as the ironclad CSS Virginia (ex USS Merrimack, also spelled Merrimac) first rammed and sank the 30-gun sailing frigate USS Cumberland, and then destroyed the 50-gun sailing frigate USS Congress with hot shot and shell. This was a cataclysmic defeat for the U.S. Navy on the day before Virginia would engage in her epic battle with the USS Monitor.

I had hardly dismounted at the water’s edge when I descried the Merrimac approaching. The Congress was moored about a hundred yards below the land batteries, and the Cumberland a little above them. As soon as the Merrimac came within range, the batteries and war-vessels opened fire. She passed on up, exchanging broadsides with the Congress, and making straight for the Cumberland, at which she made a dash, firing her bow-guns as she struck the doomed vessel with her prow.

I could hardly believe my senses when I saw the masts of the Cumberland begin to sway wildly. After one or two lurches, her hull disappeared beneath the water, guns firing to the last moment. Most of her brave crew went down with their ship, but not with their colors, for the Union flag still floated defiantly from the masts, which projected obliquely for about half their length above the water after the vessel had settled unevenly upon the river-bottom. This first act of the drama was over in about thirty minutes, but it seemed to me only a moment.

I could hardly believe my senses when I saw the masts of the Cumberland begin to sway wildly. After one or two lurches, her hull disappeared beneath the water, guns firing to the last moment. Most of her brave crew went down with their ship, but not with their colors, for the Union flag still floated defiantly from the masts, which projected obliquely for about half their length above the water after the vessel had settled unevenly upon the river-bottom. This first act of the drama was over in about thirty minutes, but it seemed to me only a moment.

The commander of the Congress recognized at once the impossibility of resisting the assault of the ram which had just sunk the Cumberland. With commendable promptness and presence of mind, he slipped his cables, and ran her aground upon the shallows, where the Merrimac, at that time drawing twenty-three feet of water, was unable to approach her, and could attack her with artillery alone.

But, although the Congress had more guns than the Merrimac, and was also supported by the land batteries, it was an unequal conflict, for the projectiles hurled at the Merrimac glanced harmlessly from her iron-covered roof, while her rifled guns raked the Congress from end to end.

A curious incident must be noted here. Great numbers of people from the neighborhood of Ragged Island, as well as soldiers from the nearest posts, had rushed to the shore to behold the spectacle. The cannonade was visibly raging with redoubled intensity; but, to our amazement, not a sound was heard by us from the commencement of the battle. A strong March wind was blowing direct from us toward Newport News.

We could see every flash of the guns and the clouds of white smoke, but not a single report was audible.

We could see every flash of the guns and the clouds of white smoke, but not a single report was audible.

The Merrimac, taking no notice of the land batteries, concentrated her fire upon the ill-fated Congress.

The latter replied gallantly until her commander, Joseph B. Smith, was killed and her decks were reeking with slaughter. Then her colors were hauled down and white flags appeared at the gaff and mainmast. Meanwhile, the James River gun-boat flotilla had joined the Merrimac.

Through my field-glass I could see the crew of the Congress making their escape to the shore over the bow. Unable to secure her prize, the Merrimac set her on fire with hot shot, and turned to face new adversaries just appearing upon the scene of conflict.[2]

Virginia exchanged broadsides with other Union warships at long range throughout the afternoon but was unable to close with them in the shallow channel. As the tide receded and dusk descended, all contestants retired to their respective anchorages. Colston continues:

And now followed one of the grandest episodes of this splendid yet somber drama. The moon in her second quarter was just rising over the waters, but her silvery light was soon paled by the conflagration of the Congress, whose glare was reflected in the river.

The burning frigate four miles away seemed much nearer. As the flames crept up the rigging, every mast, spar, and rope glittered against the dark sky in dazzling lines of fire. The hull, aground upon the shoal, was plainly visible, and upon its black surface each port-hole seemed the mouth of a fiery furnace.

For hours the flames raged, with hardly a perceptible change in the wondrous picture. At irregular intervals, loaded guns and shells, exploding as the fire reached them, sent forth their deep reverberations.

The masts and rigging were still standing, apparently almost intact, when, about 2 o’clock in the morning, a monstrous sheaf of flame rose from the vessel to an immense height. A deep report announced the explosion of the ship’s powder-magazine.

Apparently all the force of the explosion had been upward. The rigging had vanished entirely, but the hull seemed hardly shattered; the only apparent change in it was that in two places two or three of the port-holes had been blown into one great gap. It continued to burn until the brightness of its blaze was effaced by the morning sun.[3]

The rest of the story will be told in the forthcoming book, With Mutual Fierceness: The Battle of Hampton Roads for the Emerging Civil War Series.

[1] Brigadier-General R. E. Colston, C. S. A., “Watching The ‘Merrimac,’” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, vol. 1, 712.

[2] Ibid. 712-713.

[3] Ibid., 714.