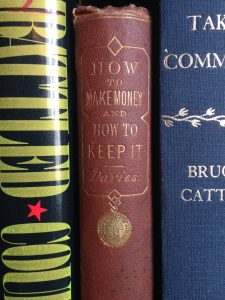

General Thomas A. Davies and How to Make Money, And How to Keep It

We remember Civil War generals for their wartime service, but rarely for what they did before or after that bloody five-year stretch. After he issued a controversial order to destroy the defenses at New Madrid, General Thomas Alfred Davies spent the remainder of the war in undistinguished administrative roles. I never gave a second thought about him, at least until I purchased a copy of his 1867 book, How to Make Money, And How to Keep It. After further investigation, I discovered that I was dealing with a remarkable individual, despite having an unremarkable career as a general during the American Civil War.

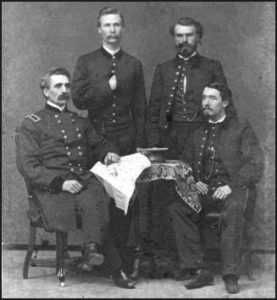

At the urging of his brother Charles, a professor of mathematics at the United States Military Academy, Thomas Davies left his family farm at the age of sixteen to prepare for admittance into the prestigious military school. After two years of preparatory education, he was admitted in 1825. He graduated four years later in 1829 (He graduated in the same class as Generals Joseph E. Johnston, Robert E. Lee, and Ormsby McKnight Mitchel, his roommate).

Davies was appointed a brevet second lieutenant in the First Infantry Regiment under Lt. Colonel Zachary Taylor and was stationed at Fort Crawford, Wisconsin. In the fall of 1830, Lt. Davies returned to the United States Military Academy to direct the improvement of the grounds; he planted trees, graveled the walkways and roads, and completed the West Point Hotel. He afterward served as the assistant engineer under Major David B. Douglass, a professor of engineering, surveying the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Railroad. Realizing that a career as a soldier would never make him a rich man or financially comfortable, he resigned his commission after two years in the army.

Davies applied for and received a clerkship with the firm Goodhue & Co. in New York. He left the firm a year later and opened his own commission and commercial business. The Panic of 1837 ruined his business, so he invested what little money he had left in buying up real estate (homes and businesses) on Manhattan Island. Through his real estate investments, Davies was able to regain his wealth. Described as being “gifted with a logical and philosophical mind,” he found success as an author, writing four religious and spiritual books before the outbreak of the Civil War, including: Cosmogony, or The Mysteries of Creation (1857); Adam and Ha-Adam (1859); Genesis Disclosed (1860); and Answer to Hugh Miller and Theoretic Geologists (1860).

Despite having been out of the army for three decades, Davies was elected colonel of the 16th New York Infantry in May 1861. He commanded the Second Brigade of the Fifth Division at the Battle of Bull Run and received an appointment as a brigadier general in March 1862. He requested to be reassigned to a western command and reported to General Ulysses S. Grant in April. Grant gave him command of the Second Division of the Army of the Tennessee.

Davies’s division was heavily engaged in the Battle of Corinth in October 1862. All three of his brigade commanders were wounded (He visited them at the Tishomingo Hotel and witnessed the death of General Pleasant A. Hackleman). Davies agreed to take command of the District of Columbus in Kentucky to replace General Grenville M. Dodge: “If it be the wish of the commanding Genl of department that I should take command of the fourth (4th) Georphical [sic] district it will be agreeable to me.”

Davies shouldered the burden of protecting Grant’s lines of communication during the Vicksburg Campaign. He had orders from General Henry Halleck to protect Columbus at all costs. Fearing it was in danger of capture by the Confederate cavalrymen, Davies ordered the guns, ammunition, and works at New Madrid to be destroyed. Enraged with the destruction of government property, Halleck felt Davies’s actions warranted dismissal.

Halleck ordered a commission set up to investigate the affair in February 1863. The three officers that made up the commission–General William K. Strong, Colonel James L. Geddes, Colonel Albert G. Brackett—found Davies “not only free from culpability” but also “honorably acquitted of all blame.” They declared, ‘That he had not only done his duty, but had performed extraordinary services to the country” and that he had acted “the part of a prudent and faithful officer in crippling the armaments at New Madrid, Mo.” Colonel Brackett defended Davies in 1891 stating that, “There can be no question that Davies did no intentional wrong, as he was as through a Union man as could be found. His desire was to do right in all things.” Despite the court’s favorable ruling, Davies spent the remainder of the war in unimportant district commands until discharged with the brevet rank of major general in August 1865.

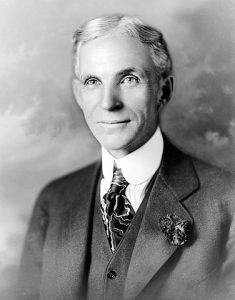

Davies resumed his career in real estate and as an author after the war. His most notable book—the only one not having anything to do with religion—was completed in 1867 after he put it off to serve in the war. How to Make Money, and How to Keep It was an instant hit. A columnist in The Nation declared on May 21, 1867, “… it is a book that we should not be sorry to see in the hands of every young man in the United States. We think it would be well for the country if this were so.” A student of Goldsmith’s Bryant & Stratton Business University, the 21-year-old Henry Ford— before founding the Ford Motor Company— found Davies’s work to be “admirable” and published a revised edition in 1884 titled, How to Make Money, and how to Keep It; Or, Capital and Labor.

‘”Reader, if you have a dollar, or work for one,” Davies began in the first sentence of How to Make Money, and How to Keep It, “you are interested in the contents of this book.” He gave detailed instructions on how to make, invest, and save money, blended with his philosophy on wealth and labor in the United States. “In this country,” Davies explained, “the fountains of wealth are open to all.” He claimed it was a “moral and political duty” of all United States citizens. Children should be taught by their parents or guardians—starting at the age of twelve— “to figure, calculate, and trade” so that they were prepared to be successful businessmen and to avoid becoming a burden to society or to their friends.

To attain the “fountains of wealth” Davies advised his readers to follow these four principles: (1) Be polite, civil, agreeable, and never fail to make everyone you come in contact with interested in yourself and what you are doing; (2) Do what you have to do for another so that he may feel that you are working for his interest; (3) Do what you have to do in the best way possible, and endeavor to improve on every repetition; (4) Be honest, candid, dignified, and social. This inspires confidence and increases character, reputation, and influence. “Such are a few of the items necessary,” Davies stated, “to success in attaining the sources of wealth.”

Davies stressed that saving money is as important as knowing how to make money. He urged his readers to live frugally. Davies proclaimed:

Expenses is the moth that eats away earnings. They are like rats and mice, or other vermin, in your granary. They consume your hard earnings invisibly, and all you know is that they are gone. Scrutinize well, then, every expenditure, and weigh its necessity. Thought costs nothing, and hence it is not expensive to think.

Those who wanted to make money should avoid a pretentious lifestyle. “Be modest, unassuming,” Davies urged his readers, “never boast of what you are doing, of your profits, or your business, or what you intend to do. Mind your own affairs, and let others alone. Make friends with all by your pleasant smiles and agreeable words; they cost nothing, and make much money.”

Not every general was destined to excel or earn fame during the American Civil War. But this doesn’t make them less remarkable individuals, as demonstrated in Davies’s case. Although he did not have the same success during the Civil War as his classmates Robert E. Lee and Joseph E. Johnston, Thomas Davies rose to the occasion and faithfully served his country. Instead, he thrived as a businessman and an author before and after the war, leaving behind a book filled with proverbs that are still relevant to businessmen, investors, and anyone looking for financial guidance 150 years later.

Bibliography

Army and Naval Journal, December 19, 1863.

Brackett, Albert G. “The Evacuation of New Madrid by the Federals.” The United Service 5 (February 1891): 182-187.

Davies, Thomas A. How to Make Money: And How to Keep It. New York: G.W. Carleton & Co., 1867.

Ford, Henry A. How to Make Money, and how to Keep It; Or, Capital and Labor. Detroit: The Chamberlain Publishing Co., 1884.

Grant, Ulysses S. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 5: April 1-August 31, 1862, Edited by John Y. Simon. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1973.

Grant, Ulysses S. The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, Volume 6: September 1-December 8, 1862, Edited by John Y. Simon. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1977.

Hubbell, John T. and James W. Geary, eds. Biographical Dictionary of the Union: Northern Leaders of the Civil War. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995.

Plummer, Mark A. Lincoln’s Rail-Splitter: Governor Richard J. Oglesby. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001.

Smith, Derek. The Gallant Dead: Union and Confederate Generals Killed in the Civil War. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2005.

The Nation, May 2, 1867.

The Times, August 21, 1899.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Record of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Volume 22. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902.

“Thomas A. Davies. No. 565. Class of 1829.” http://www.usma.edu/ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/Army/USMA/AOG_Reunions/31/Thomas_A_Davies*.html.

Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

Welsh, Jack D. Medical Histories of Union Generals. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1996.

Wonderful post.

I wonder if Davies was removed by Halleck due to personal problems. Halleck played favorites, and Grant often ingratiated himself with Halleck by favoring Halleck’s friends, such as Sherman, McPherson, Hurlbut and Sheridan.

I wonder if Davies was friendly with Rosecrans? Such a friendship was increasingly the kiss of death for a number of officers.

I doubt that Davies was friendly with Rosecrans after how 2nd division was abused and insulted by Rosecrans at Corinth.

He believed in “A penny saved is a penny earned.”

A very interesting article. Your lead paragraph about the guy hooked me. Loved Davies’ good hearted philosophy of investing and savings. Since you read the book have you reinvested your IRA account?