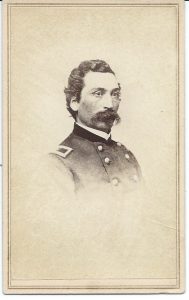

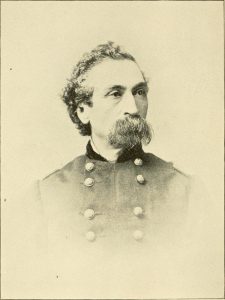

Artillery: General Davis Tillson

Six men who suffered the loss of a limb before the American Civil War—Joseph A. Haskin (U), Philip Kearny (U), William W. Loring (C), James G. Martin (C), Thomas W. Sweeny (U), and Davis Tillson (U)—overcame their handicaps and rose to the rank of brigadier general or major general during the war. Of these six generals, Davis Tillson was the youngest and the only one not to have had a limb amputated as a result of being wounded during the U.S.-Mexican War. He also made the greatest climb in rank of his fellow invalids, beginning the war as a lowly captain of artillery, and ending it as a brevet major general and commander of the District of East Tennessee.

Six men who suffered the loss of a limb before the American Civil War—Joseph A. Haskin (U), Philip Kearny (U), William W. Loring (C), James G. Martin (C), Thomas W. Sweeny (U), and Davis Tillson (U)—overcame their handicaps and rose to the rank of brigadier general or major general during the war. Of these six generals, Davis Tillson was the youngest and the only one not to have had a limb amputated as a result of being wounded during the U.S.-Mexican War. He also made the greatest climb in rank of his fellow invalids, beginning the war as a lowly captain of artillery, and ending it as a brevet major general and commander of the District of East Tennessee.

The son of William and Jane Tillson, Davis Tillson was born in Rockland, Maine, on April 17, 1830. In July 1849, Davis received an appointment to United States Military Academy. (The same year as John B. Hood, John M. Schofield, and James B. McPherson.)

Cadet Tillson suffered a puncture wound to his leg during an accident the same month he arrived at West Point. He continued to have problems with his leg during the summer and into the winter of 1849. When his condition grew worse, the surgeon decided to amputate the infected portion of his leg. The procedure was conducted at the U.S. Hospital at Governors Island on March 23, 1850.

Tillson returned to the academy at the end of April but was never the same. He could only walk with the aid of crutches, making it nearly impossible for him to march, drill, or ride a horse. He must have felt embarrassed and humiliated. He resigned from the academy by September 1851.

Tillson returned home to Maine after his resignation. But he did not wallow in despair. He served as a civil engineer for a while before turning to politics. He was elected to the Maine legislature on the Republican ticket in 1857. The next year, he was appointed as adjutant general of the state. President Abraham Lincoln appointed him as the collector of customs of Waldoboro, Maine, in July 1861, the same month as the Union defeat at Bull Run.

Tillson did not intend to sit back in a comfy desk job while his fellow Mainers fought and died on the battlefield. He could have (and probably should have) remained at home. He earned a reputation in the community as a “gentleman of military taste and culture” and helped to drill Captain (afterward a general) Hiram G. Berry’s Rockland City Guards (a local militia unit) in the years before the war. He knew a thing or two about soldiering, and despite his disability, Tillson resigned his position as a collector of customs and organized the 2nd Maine Battery.

He feared that he would be rejected when he showed up to be mustered into service. The famed prohibitionist, Neal Dow, then serving as colonel of the 13th Maine Volunteers, said that Tillson had anxiously come to him before going to the mustering station. “I am afraid I cannot pass muster with that officer,” Tillson said to Dow. “He was a classmate of mine at West Point and knows my defect, which no stranger would suspect.”

But Dow tried to reassure his friend that his handicap wouldn’t be detected. “He had been so admirably fitted with a cork substitute and had become so wonted to its use,” Dow wrote, “that no one unacquainted with the facts would have suspected his ‘unsoundness.’” Tillson had been wearing an artificial leg under his slacks since 1852.

Dow accompanied him to the mustering station in case he needed to intervene on Tillson’s behalf. He soon discovered it wasn’t necessary. “I found that no word from me was needed,” Dow recalled. “They recognized each other instantly, and upon Captain Tillson expressing his fear of rejection his old classmate replied: ‘Tillson, I know you. I would pass you if you had lost both legs and arms.’” Tillson was mustered into service as a captain of the 2nd Maine Battery in November 1861.

During the winter of 1861-62, the regiment was stationed at Fort Preble in Portland, Maine, during the Trent Affair. Tillson took the opportunity to drill his green command and transformed it into an effective artillery unit. In April 1862, the battery was assigned to the Department of the Rappahannock under General Irvin McDowell.

In May, Tillson was promoted to major and made chief of artillery of General Edward O.C. Ord’s division (afterward commanded by General Ricketts) and served in this capacity until August. He fought in the Battle of Cedar Mountain on August 9, 1862. McDowell must have been impressed with his performance because the day after the battle he made Tillson the chief of artillery of the III Corps. He served as McDowell’s chief of artillery for the remainder of the campaign culminating in the Union defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run.

After the Union defeat, Tillson applied for thirty days’ leave due to his poor health and to have his damaged artificial limb repaired. After the war in 1888, Tillson would write to A. A. Marks, a manufacturer of artificial limbs, praising his design. “For the past ten years I have worn constantly one of your rubber feet,” Tillson wrote, “It very far surpasses all others in durability, absence of disagreeable noise, and freedom from unpleasant concussion in walking.” But in 1862, Tillson did not possess Marks’ model and likely had to endure the annoyance and discomfort he described in the field with an unserviceable limb.

Tillson returned to the army in October and reported to Lt. Colonel Joseph A. Haskin (a fellow invalid and future general), in charge of the capital’s defenses north of the Potomac River. He was made inspector of artillery at Washington, D.C. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel in January and was commissioned a brigadier general in March. But unlike Haskin, who remained in Washington’s defenses for the remainder of the war, Tillson was assigned to a more active command. He was ordered to report to General Ambrose E. Burnside, commander of the Department of Ohio, in Cincinnati.

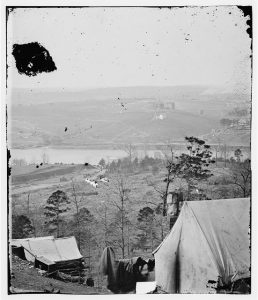

Burnside put General Tillson in charge of inspecting the defenses at Covington and Newport (Kentucky) and appointed him chief of artillery of the department. During the summer and fall of 1863, Tillson supervised the repair of the defenses of Cincinnati and the Louisville and Nashville Railroad. He was made chief of artillery to General John G. Foster, who had replaced Burnside in December 1863, and was ordered to report to Knoxville following General Longstreet’s unsuccessful campaign. He was given command of the defenses of Knoxville, Loudon, and Kingston and was ordered to supervise the improvement of their fortifications.

When General Ulysses S. Grant visited Knoxville during the winter of 1863, Tillson requested permission to raise a regiment of colored heavy artillerymen. General Foster issued an order on January 6, 1864, granting Tillson’s request to recruit a colored unit to defend Knoxville: “All able-bodied colored men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five within our lines, except those employed in the several staff departments, officers’ servants, and those servants of loyal citizens who prefer remaining with their masters, will be sent forthwith to Knoxville, Loudon, or Kingston, Tenn., to be enrolled, under the direction of Brig. Gen. Davis Tillson, chief of artillery, with a view to be the formation of a regiment of artillery, to be composed of troops of African descent.” The unit was designated as the 1st U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery and remained under Tillson’s command for the remainder of the war.

He wrote to the adjutant general of Maine, John L. Hodsdon, from Knoxville on April 2, 1864, expressing his confidence in the improvements that he had made since Longstreet’s campaign. He also spoke of General William T. Sherman’s approval of his work and his devotion to his new assignment:

Since my arrival here, I have been very busy in constructing the fortifications about this city. It is not too much to say that I have made them at least one hundred fold stronger than they were at the time Longstreet made his attack. A few days since Major Gen. Sherman, commanding Military Division Mississippi, accompanied by his Chief of Artillery, Gen. Barry, examined the works, and both expressed themselves highly gratified with the plan and execution of the line. Have some 4,000 troops of all kinds under my command, and work some 1,000 every day…I take some little pride in the works here, and mean to make this the best fortified town in this country.

In January 1865, Tillson assumed command of the District of East Tennessee (Department of Cumberland) from General Jacob Ammen. He led Ammen’s old Fourth Division of the XXIII Corps during General George Stoneman’s raid from March to April 1865. His two brigades played a crucial role during these operations, protecting Stoneman’s rear during his advance into North Carolina and Virginia.

Receiving intelligence in April that President Jefferson Davis fled from Goldsboro and was headed west with his treasury wagons, General Stoneman gave Tillson orders to push on to Asheville and hold the pass in the Blue Ridge in order to cut-off Davis. “If you can hear of Davis,” Stoneman wrote to Tillson, “follow him to the end of the earth, if possible, and never give him up.” Davis was finally captured by Union cavalrymen on May 10, 1865. Tillson was brevetted major general at the close of the war.

Tillson submitted his resignation when the war ended but it was not accepted. Instead, he was appointed to serve as acting assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau in Georgia, with his headquarters in Augusta. General Oliver Otis Howard, the Freedmen’s Bureau commissioner, praised Tillson for his “faithful work” and “great purity of administration” during the time he filled this role. Howard wrote to President Andrew Johnson telling him that Tillson was a man of “highly commended by the inspectors, and is known to be a man of integrity and good judgment.” He remained on duty with the Freedmen’s Bureau until December 1866.

Rockland, Maine (Find A Grave).

Tillson’s service as an administrator translated well to his business career after the war. He purchased Rockland’s Hurricane Island for $1,000 in January 1870 and organized the Hurricane Island Granite Co. to develop its granite quarries, employing an army of 1,400 European workers. He invested in a handful of other business ventures, including a lime quarry and orange groves in Florida. He took a risk and built what became known as the Tillson Wharf in 1881—it cost him $200,000 to construct—but it turned out to be his greatest financial success. Tillson died in Rockland from heart complications on April 30, 1895, at the age of 65 years old.

He may not be as well-known as his fellow generals from Maine, but Davis Tillson quickly rose through the ranks and held a number of important commands during the war. By the age of 35 years old, he commanded a district. He was an excellent artilleryman, administrator, and builder of fortifications. While he would have been justified staying home, Tillson chose to volunteer his services despite his handicap and admirably served his country.

Bibliography

Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine, for the Year Ending December 31, 1861. Augusta, ME: Stevens & Sayward, 1862.

Annual Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Maine, for the Year Ending December 31, 1863. Augusta, ME: Stevens & Sayward, 1863.

A Treatise on Mark’s Patent Artificial Limbs With Rubber Hands and Feet. New York: A.A. Marks, 1888.

Dow, Neal. The Reminiscences of Neal Dow. Recollection of Eighty Years. Portland, ME: Evening Express, 1898.

Executive Documents Printed by the Order The House of Representatives During the Second Session of the Thirty-Ninth Congress, 1865-66. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1866.

Executive Documents Printed by the Order The House of Representatives During the Second Session of the Thirty-Ninth Congress, 1866-67. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1867.

Gould, Edward K. Major-General Hiram G. Berry: His Career as a Contractor, Bank President, Politician and Major-General of Volunteers in the Civil War. Rockland, ME: Press of the Courier-Gazette,1899.

Hartley, Chris J. “Major General George Stoneman Led the Last American Civil War Cavalry Raid.” America’s Civil War (May 1998). Accessed June 2, 2018. http://www.historynet.com/major-general-george-stoneman-led-the-last-american-civil-war-cavalry-raid.htm.

Howard, Oliver O. Autobiography of Oliver Otis Howard, Major General U.S. Army. Vol. II. New York: Baker and Taylor Company, 1908.

“In Memoriam: Davis Tillson.” The Maine Bugle (Rockland, ME), October 1895.

“Island History.” Hurricane Island Foundation. Accessed June 2, 2018. http://www.hurricaneisland.net/history/.

Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America From December 6, 1858, to August 6, 1861, Inclusive. Vol. XI. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1887.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series I, Vol. XLIX, Part II (Correspondence, Etc.) Washington: Government Printing Office, 1897.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series III, Vol. IV. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1900.

Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964.

Welsh, Jack D. Medical Histories of Union Generals. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1996.

1 Response to Artillery: General Davis Tillson