The Trust’s Teacher Institute: Helping Teachers Teach History More Effectively

“What do historians do?” Bruce Lesh asks the room full of social studies teachers.

“What do historians do?” Bruce Lesh asks the room full of social studies teachers.

The teachers offer answers: Solve problems. Research. Write. Argue.

“In that discussion, we leave out the only thing we do in the classroom,” Lesh points out. In the list of responses, no one says “Memorize information.”

Research shows that students want to mimic, in their social studies classrooms, the things historians do. “They understand that history is about information, but they want to be able to explore that information,” Lesh says. They want context. They want a reason.

Instead, history education overemphasizes memorization, and memorization “doesn’t lead to achievement or student engagement,” Lesh says.

If I could take one presentation from the 2018 American Battlefield Trust’s Teacher Institute and ship it around to every Civil War Roundtable in the country—and every school board and every state department of education—it would be Bruce Lesh’s Friday morning talk, “‘It’s not what or how much we teach, but how we teach it that matters’: Confronting the Legacy of History Instruction.”

Lesh is a former social studies teacher who now works in education policy at the state level in Maryland. In 2008, the Organization of American Historians recognized him as the pre-collegiate Teacher of the Year; in 2013 was named Maryland Secondary Social Studies Teacher of the Year.

Lesh’s brilliant talk struck to the heart of a problem I hear all the time when I’m on the road talking to Civil War groups. So many buffs worry that students today don’t seem to know history very well.

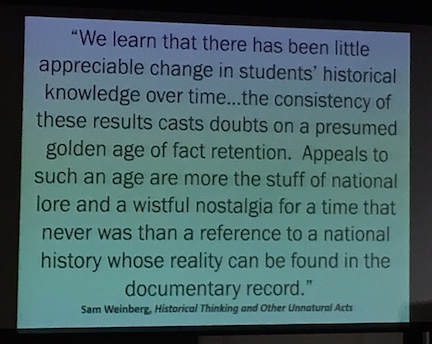

Lesh started with that very point. He shared a news story that lamented a poor level of historical literacy among students. What year do you think that’s from, he asked. While it sounded like something from a contemporary publication, it came from a 1917 report that tested 1500 Texas students to determine their sense of history.

“We’re used to hearing this particular story,” Lesh says, “that students are bad at history…. This is the kind of narrative that’s promoted by people like David McCullough who go before Congress to testify about the lamentable state of historical literacy.”

The narrative is there, he says. We’ve heard it all the time. “It’s become popular to bash teachers,” he adds. “Teachers get the blame.”

The narrative, though, is wrong.

“The good news is that there’s not a single piece of data that shows students knowledge of history is in decline,” says Lesh. The bad news: “Students’ knowledge of history is consistently low.” In other words, it didn’t just suddenly get bad—it’s always been bad.

“The good news is that there’s not a single piece of data that shows students knowledge of history is in decline,” says Lesh. The bad news: “Students’ knowledge of history is consistently low.” In other words, it didn’t just suddenly get bad—it’s always been bad.

When he began teaching, he taught the way he had been taught. “And my students looked like they were at a visit to the dentist’s without any Novocain,” he admitted. The problem, he discovered through his own experience and through subsequent research, is that teachers get trapped “in a system that perpetuated a low level of proficiency.”

“We teach history the same way in 2018 that we taught it in 1890,” he says. “And in 1890 there was no electricity. There was no VCR. There was no one-to-one.” The biggest change: “We no longer have students recite by memory speeches.”

Essentially, “the mode of history instruction has not changed.” And if that mode of instruction resulted in poor achievement in 1917, it isn’t going to get any better by 2018. “Assessment and accountability has reinforced this persistent instruction and use of a single source,” he says, referring to the 70-90 percent of teachers who use a textbook as their single source of information in their classrooms.

Lesh lamented the increased culture of testing in schools. He pointed to Virginia’s assessment program, the Standards of Learning—or “SOLs,” as they’re called for short. He invites the teachers in the room to consider that acronym for just a moment. “Is it any wonder?” he asks as everyone gets the joke (which he doesn’t explicitly say, so I will: “Shit Out of Luck”).

Virginia’s SOLs feature 300 statements of “essential content” students need to know. Facts to memorize. As a result, he says, “I see more teachers looking at history as an exercise in trivia—the SOLs reinforce that.”

“Outside this room, people don’t love our discipline,” Lesh warns. He cites research that asked respondents to describe the field of history in one word.

“History is boring!”—that was the single most frequent description, and negative descriptions significantly outweighed positive ones. The other negative responses were simply synonyms for “boring.”

A complicating factor in the field now is that many students can opt to take online courses. The number one course they choose to take online are history courses—an alarming development to Lesh because, he says, it means, “Our practices are not meeting the needs and demands of students.”

So, he asks the teachers in the room, if methodology and student outcomes are the problem, what’s the solution?

Students don’t like being given an answer. They don’t like being given the facts.

They like to have something to figure out.

And isn’t that what historians do? This is when he asks the room full of teachers to explain the main job functions of a historian.

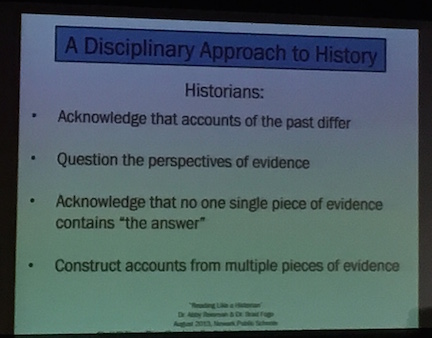

After developing the job description list, Lesh synthesizes the information:

- Historians ask questions that frame a problem for them to research.

- Historians gather and ask questions of a variety of sources.

- Historians develop, defend, and revise interpretations.

- Historians argue in their books and through their publications.

“Questions are powerful tools,” he says.

A question can help students organize and remember information. It can better facilitate engagement and retention.

A question can help students organize and remember information. It can better facilitate engagement and retention.

Curiosity releases dopamine, a neurotransmitter that helps improve attention and remembering.

For teachers required to teach information—like the SOLs—figure out what the question was that someone asked which then led them to add the “required fact” to the list.

In his research, Lesh has found a recurrent theme from students, who say, “I want to do something in history class.”

Lesh suggests creating a history lab that puts students in a situation where they have to take a disciplinary approach to history instruction. They can do what historians do and, in doing so, learn the material they’re required to learn in a way that boosts achievement and retention.

But, he offers a cautionary note, too. “I don’t sell this as a silver bullet,” he warns. “It’s not going to help you when a kid comes to school hungry. When a kid comes to school once every couple of weeks. But it is a way to get them to eat their vegetables and get them to know what they need to know.”

Thanks Chris for this article. In his book, ” ‘Why Won’t You Just Tell Us the Answer?’: Teaching Historical Thinking in Grades 7-12,” Bruce Lesh has a lot of practical ideas for engaging students and leading them to think critically about historical and current events. The book would make a worthwhile addition to your summer reading list if you are a teacher, National or State Park ranger, guide or volunteer, or just are interested in learning some effective methods for getting kids interested in and hooked on history.

For those of us who teach, Common Core was a bright light in a long, dark tunnel. But whomever was in charge of rolling it out to the nation as a whole certainly bungled the job, as that bright light has gone down in flames in many states. I taught Math, and when I got serious (i think) kickback for asking my students to bring a calculator to class–well–one just has to wonder. This entire conference has been one that has brought tears and smiles. Thanks to the Trust, to Kris, and to all of you.

For those who might wonder why I taught Math, it was because I was told that, in 5th grade, history was no longer important and besides, having “those people from Williamsburg” would just take up too much time. Sometimes a person just has to walk away. Anyway–great job, all!