Railroads: The B&O and the Battle of Monocacy

Eric Wittenberg has written an overview of the B&O here. The following blog post examines the B&O’s role more in depth as it pertains to the events leading up to the Battle of Monocacy.

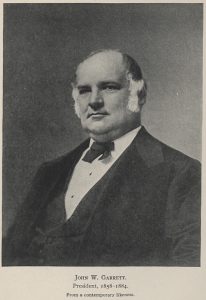

Messages kept coming across the desk of 43-year old John W. Garrett. They told of Confederate forces, with unknown size, moving down the Shenandoah Valley towards the Potomac River. And for the president of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, that meant his entire company was in danger.

With tracks and trains running into the Ohio Valley, Garrett worried what kind of damage those Confederate soldiers could do if left unopposed. And so he started to wire officials in Washington, raising the alarm and trying to get someone, anyone, to listen to his concerns. Garrett’s first wire, dated on June 29 1864, read: “I find from various quarters statements of large forces in the Valley. Breckinridge and Ewell are reported moving up. I am satisfied the operations and designs of the enemy in the Valley demand the greatest vigilance and attention.” But to Garrett’s chagrin, no one in Washington took the warning very seriously.

General-in-Chief of the U.S. Army Ulysses S. Grant, for example, wrote that the Confederate forces Garrett worried about were at Petersburg, and “There are no troops that can be threatening” the lower Shenandoah Valley except some scattered cavalry units. As Garrett continued to receive more and more communications from his railroad’s employees, he got more and more impatient. And so, on July 2nd, Garrett decided to pay a visit to someone he hoped would pay better attention. That man was Lew Wallace, commander of the Middle Department, which was headquartered in Baltimore. Meeting in the Eutaw House hotel, then Wallace’s headquarters, Garrett convinced Wallace of the urgency of the situation. Garrett’s concern was specifically the iron railroad bridge that spanned the Monocacy River, just south of Frederick, Maryland. Garrett also expressed worry about the railroad’s safety at Harpers Ferry and Point of Rocks, further down the tracks.

The meeting in Wallace’s headquarters began a partnership that over the next seven days would move men and resources to not only the Monocacy, but also endangered points throughout Maryland and the area surrounding Washington D.C. Before Garrett left Wallace’s headquarters, the general told the railroad president, “You may take with you my promise- the bridge shall not be disturbed without a fight.”

While Wallace set out to command at the Monocacy, it fell on Garrett’s shoulders to cover the logistics of moving the necessary troops. And over the next few days, John Garrett did his job masterfully. Alongside Garrett was William Prescott Smith, Master of Transportation for the B&O. Together, Garrett and Smith made telegrams fly in all directions. Smith’s network of agents continuously kept him and the railroad’s president up to speed. “Engine 38 with 26 loads [of] troops, horses and baggage for Harper’s Ferry left at 7’oclock,” read one from July 5. Another, from the same day, “Extra engine 38 with troops from Washington for Harper’s Ferry and engine 132 with battery passed here at 9:30 a.m., making good time.”

The telegrams kept coming, and the railroad men kept working. Fortunately, the high command of the U.S. Army had caught on to the threat of Confederate forces moving against Wallace. Moving out of the trenches on July 6, the 3rd Division of the Army of the Potomac’s 6th Corps loaded onto steamers and made their way up the Chesapeake Bay. And when those soldiers arrived in Baltimore’s harbor, railroad agents from the B&O awaited them with rolling cars ready to go. Loaded onto those trains, the veteran soldiers were whisked towards the Monocacy, where Wallace’s band of inexperienced troops had already made contact. Arriving at the Monocacy Junction on July 8, the 6th Corps soldiers finished a two trek that saw them hustled from point to point. They arrived in just in time to help fight the Battle of Monocacy.

That fight, which took place on July 9, came to be known as the “Battle that Saved Washington.” Though defeated, Wallace’s forces had delayed long enough for further reinforcements to get sent to the Federal capital and fall into the forts. None of those actions, however, could have been possible without John Garrett, William P. Smith, or the legion of railroad workers who sprang to action in the early days of July, 1864.

Lew Wallace kept his promise to fight for the iron bridge, but was unable to hold it. The Confederates destroyed a lot of B&O buildings at Monocacy, but were unable to destroy the iron bridge. The B&O workers arrived quickly after the battle, repaired the damage to the bridge and put it back into operation. Halleck rewarded Wallace by relieving him.

They sent the wrong troops. They should have sent the “Iron Bridgade”. tee hee.

Many do not understand that the reason the new state of West Virginia has an Eastern panhandle was to keep the B&O in Union territory. They still were attacked by Confederates but in Union State. Look at a map and you will see the tip of the panhandle is where the B&O leaves Maryland. While not a cabinet member Mr. Garrett had an open invitation to attend their meetings. The B&O also built the first Presidential Car that was only used by Lincoln when his remains were taken to a location unknown to many for his burial. But the importance of the B&O in moving forces and supplies aided West Virginia being created and why that panhandle exist.