Two Union Veterans: The Election of 1880, Part 2

Part 2 of 2 in a short series. Find Part 1 and details about the presidential candidates here.

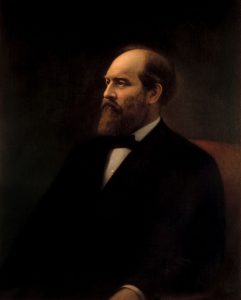

During the presidential campaign that followed, both Garfield and Hancock attempted to follow the era’s tradition that candidates did little actual campaigning. The parties did most of the heavy lifting. Garfield remained at home in Mentor, Ohio, where nearly 20,000 people descended on his farm between his nomination in June and the November election. Garfield eventually began giving speeches from the front porch of his home, and today this is considered the first-ever “front porch” presidential campaign. Garfield spoke little about himself; his speeches were mostly about general patriotic themes and the great deeds and history of the Republican Party. He also masterfully tailored his speeches to the groups there to visit him, which included businessmen, ladies’ organizations, first-time voters, German immigrants, African American Civil War veterans, and others. On the Democratic side, Hancock also remained at home for most of the campaign. As commander of the U.S. Army’s Division of the Atlantic, his home was on Governor’s Island in New York City. Reporters and others made their way as well, though not in the same numbers that traveled to Garfield’s home in Ohio.

The Republican and Democratic platforms were not vastly different in 1880. The major difference was on tariffs, which the Democrats viewed as being “for revenue only.” Republicans accused the Democrats of being unsympathetic to the needs of the laborers and manufacturers who would benefit from a high protective tariff. Hancock made the issue worse when, in one of the few newspaper interviews he did during the campaign, he tried to brush off the tariff as nothing more than “a local question.” Republicans, hesitant to criticize a genuine Union war hero too harshly about slavery and secession, jumped on the comments as demonstrating not only the Democratic Party’s lack of concern for American industry but also Hancock’s inexperience with political issues. Taking this attack one step further, the Republican National Committee printed a pamphlet entitled A Record of the Statesmanship and Political Achievements of Gen. W.S. Hancock. It contained only blank pages.

One of the campaign’s most dramatic and important moments came on August 6, 1880, when Garfield was in New York City for a Republican meeting. (The meeting was really just an excuse to get the candidate and New York Senator Roscoe Conkling together in the same room to try to mend discord between the party’s rival factions, but Conkling blew off the meeting with Garfield.) That night, Garfield addressed a huge crowd outside Republican headquarters and reminded everyone about the party’s history but also the nation’s obligations to ensuring civil rights for all:

“Soon after the great struggle began, we looked behind the army of white rebels, and saw 4,000,000 of black people condemned to toil as slaves for our enemies; and we found that the hearts of these 4,000,000 were God-inspired with the spirit of Liberty, and that they were all our friends. We have seen white men betray the flag and fight to kill the Union; but in all that long, dreary war we never saw a traitor in a black skin. Our comrades escaping from the starvation of prison, fleeing to our lines by the light of the North Star, never feared to enter the black man’s cabin and ask for bread. In all that period of suffering and danger, no Union soldier was ever betrayed by a black man or woman. And now that we have made them free, so long as we live we will stand by these black allies. We will stand by them until the sun of liberty, fixed in the firmament of our Constitution, shall shine with equal ray upon every man, black or white, throughout the Union.”

Garfield was one of the few Republicans still publicly talking about civil rights in 1880. Even many of the most radical former Radical Republicans had moved on to other issues by then and were searching for new alliances to help the party maintain power. They often found those alliances with wealthy industrialists and financiers, and before long the Republicans were thought of by many as the party of “big business.” But in 1880, James Garfield tried to remind his fellow Republicans and the American people why the party had been created in the first place and keep it true to its roots as a party seeking opportunity for all Americans. (Admittedly, even many of the most progressive Republicans on racial issues were unconcerned about the fates of American Indians.)

In the end, the popular vote was agonizingly close. Garfield came out on top, but only by about 10,000 votes of several million cast. His Electoral College victory was more decisive: 214 to 155. To his credit, Hancock accepted the results in stride. When his wife told him the morning after Election Day, “It has been a complete Waterloo for you,” the General replied, “I can stand it.” He graciously attended Garfield’s inauguration on March 4, 1881.

Garfield continued to beat the drum on civil rights during his inaugural address, stating that “the elevation of the Negro race from slavery to the full rights of citizenship is the most important political change we have known since the Constitution of 1787.” The next four (or perhaps eight) years certainly appeared to have the potential to be good ones with such a thoughtful leader at the helm. But it was not to be. President Garfield was assassinated just a few months into his term. Who knows just how differently American history might read today had Garfield lived? Or, for that matter, had Hancock won the election?

James Garfield had served the Union honorably during the Civil War, rising to the rank of major general before leaving the Army at the end of 1863 to take a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. In any other election of the era, his military service alone might have gotten him to the White House. But in 1880, the Democrats ran a soldier in Winfield Scott Hancock with a far longer and more impressive military record than Garfield. Though Hancock fell just short of the White House, the Democrats would finally succeed in 1884 when Grover Cleveland became the first Democrat elected president since James Buchanan in 1856.

The presidential election of 1880 is often overlooked but was a critical one in American history. It was the only time two Union veterans ran against one another for the nation’s highest office. It also laid bare the changes taking place in both parties, many of which we continue to live with even today.

Hancock more accurately reflected the conservative/McClellan wing of the Army of the Potomac’s command staff. He had little use for most of the more radical political acts of the Lincoln administration, though he hid his opposition much better than did his superior. Garfield, on the other hand, plays better today, if only because he talked the talk we wish to hear. But during the War he was viewed with suspicion by members of Rosecran’s staff as a political intriguer, visiting his mentor Chase to complain about the perceived lack of aggressiveness on the part of his chief. He was adept then in talking the talk that he knew his ultimate superiors would want to hear. One often wonders what his true beliefs were.

Gee, I wish in this day of advancing technology that most political campaigns can be mounted from candidates porches! It would certainly save on all the travel expenses!

Good two part post. I have a question and a comment.

“Garfield tried to remind his fellow Republicans and the American people why the party had been created in the first place and keep it true to its roots as a party seeking opportunity for all Americans. (Admittedly, even many of the most progressive Republicans on racial issues were unconcerned about the fates of American Indians.)” – What was Garfield’s take on Chinese immigrants? I know the COP was generally not very progressive on this issue or the Irish to be fair, which is why the Irish voted Democratic until the 1970s.

“James Garfield had served the Union honorably during the Civil War, rising to the rank of major general before leaving the Army at the end of 1863 to take a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives.” – Garfield had a pretty mixed record. He betrayed Rosecrans (not exactly honorable) and he was the author of Streght’s Raid. That said, his advice to Rosecrans to attack in May 1863 was wise. He was devoted to civil rights. It was not just a political tactic.

Garfield was also a Lothario of sorts.