From West to East – John Pope and Counter-Insurgency, Part I

“I have come to you from the West,” declared Major General John Pope, as he addressed his new Army of Virginia. The new commander continued, “we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary and to beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defense.” Pope hoped to lead this new army to victory and to effectively smother the flames of resistance in northern Virginia. To achieve his goal, he utilized the policies and strategies he previously used while serving in northeastern Missouri. This analysis will look primarily at counter-insurgency policies Pope implemented in Missouri and how they were applied to the equally unstable, yet vastly different, region of northern Virginia.

When John Pope arrived in Washington, DC on June 24, 1862, he had an impressive military record. Not only was he a Class of 1842 graduate of the United States Military Academy, Pope served in the U.S. Army as an engineer, including experience in the Mexican War. By 1862, he successfully captured the Confederate strongholds, as well as their respective garrisons, along the Mississippi River at Island No. 10 and New Madrid, Missouri. His use of combined-arms was also praised by the Union high command, which earned him a field promotion in the spring of 1862. It was not only his combat experience that piqued the interest of the Lincoln Administration, though.

Unlike many other commanders, Pope also had a unique early-war experience in counter-insurgency operations, specifically during his tenure as commander of the District of North and Central Missouri in 1861. According to Pope himself in his post-war memoirs, Missouri was incredibly unstable: “no laws were observed or executed and the people thus left without a government and inflamed with enmity … Such was the situation in North Missouri when I entered that district.”[1] Soon after crossing into Missouri from Illinois on July 17, he developed a plan with a simple, yet complicated, backbone – make the civilians responsible.

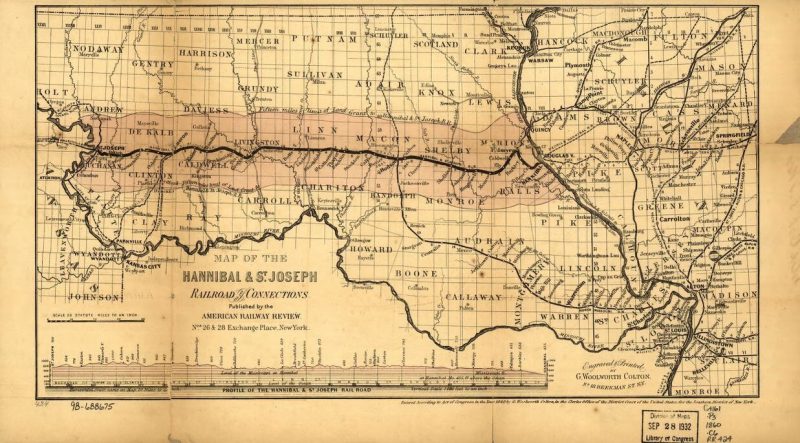

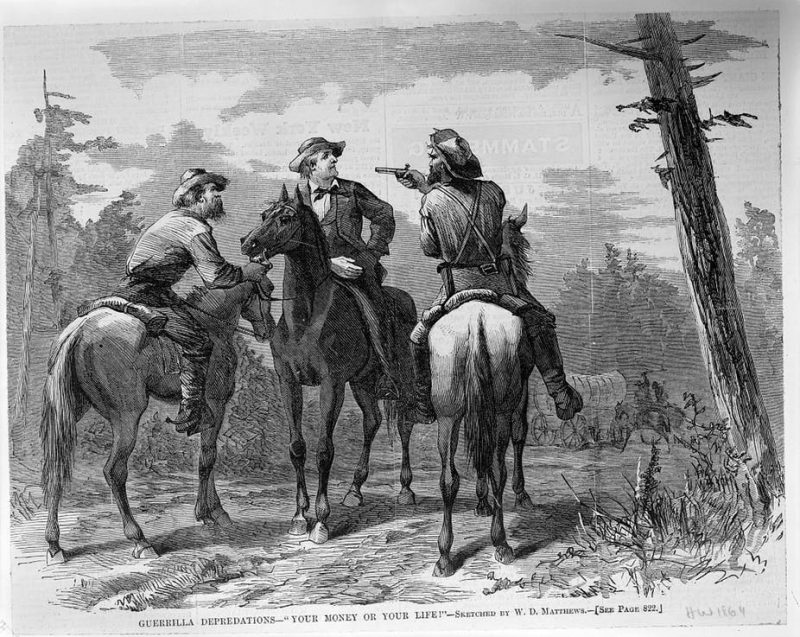

The strategic situation in Northern Missouri was complex. The Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad line split the district north-south and was a major line of supply and communication for the Department of the West. “Lawless parties of marauders” ran rampant through the region and attacked the vital lines of communication, specifically the Hannibal and St. Joseph. To quell these marauders, Pope believed he needed to make the population along the railroad line “directly responsible” for their actions by paying for the cost of destruction. More importantly, the actions of insurgents would result in punishment “laid upon the shoulders of their friends and relatives.”[2] In addition, the area along the railroad would be divided into administrative divisions, which would then be led by civilians, who were also completely responsible for what happens in their division. To make his authority known across the entire region, Pope extended this order to the rest of the district one week later. His well-conceived plan to show dominance over insurgency, though, would soon backfire in an unexpected way.

Instead of treating non-combatants and innocent civilians with respect, Pope’s troops went overboard. According to the civilians, many were arrested, homes searched and seized, and property confiscated and stolen – all without probable cause.[3] The abuses throughout the district forced Department of the West commander John C. Fremont to intervene. He declared martial law throughout the state. Though both the residents of the district and Fremont believed Pope’s policies were out-of-line, Pope himself felt that he had the situation under control, with the exception of Marion County, where guerrillas still pounced in night raids. Pope later described his ill feelings toward Fremont’s declaration, “Instantly small detachments of troops appeared everywhere, accompanied by that necessary evil of martial law, the provost marshal.” To him, the provost marshals were “like the lice of Egypt,” because they “soon infested every place and tormented everybody.”[4] Pope was bitter. When he finally made his way east to command the Army of Virginia the next year, he wanted to prove that his policies could work.

To be continued …

Sources:

[1] John Pope, The Military Memoirs of General John Pope, edited by Peter Cozzens and Robert I. Girardi (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 18.

[2] Ibid., 19.

[3] Daniel E. Sutherland, A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 21.

[4] Pope, The Military Memoirs of General John Pope, 25.

Excellent post. Thank you.

Thanks for reading, Sean! Glad you liked it.

John Pope: impressive on paper… This officer was on active service at outbreak of the war, and was ranked first among the Generals from Illinois when the Official List of Brigadier Generals appeared in late August 1861. Sent to Northern Missouri, BGen Pope focused more on disciplining subordinate commanders than maintaining control of the Hannibal & St. Joseph R.R. and was caught short when an express passenger train on that line was derailed outside St. Joseph. Now focused on rebuilding the damaged bridge, General Pope delayed sending a two-pronged, poorly coordinated pursuit of Rebels fleeing south from St. Joseph, the Rebels in possession of 100 wagons full of loot stolen from citizens and businesses of St. Joseph. Because of the delay, an inconsequential skirmish was fought at Blue Mills Landing; and the 100 wagons (which also contained powder and ammunition) arrived safely to reinforce Sterling Price outside Lexington; and Lexington fell.

Pope benefited shortly afterwards by the arrival of his friend, Henry Halleck, Major General in command of the Department of the Missouri. Benjamin Prentiss was given charge of Missouri north of the Missouri River; and John Pope was assigned to the capture of New Madrid… which was brilliantly accomplished by marching his army through forty miles of “Impenetrable swamp.” On April 8, 1862 now-Major General Pope took the Surrender of the remaining Rebels near Island No.10 who had not surrendered to Flag-Officer Foote.

Pope and his Army of the Mississippi then joined Halleck in the field in the Slow Crawl to Corinth, taking possession of the abandoned town end of May 1862. And MGen Pope was sent south to manage pursuit of Beauregard’s retreating Army… stringing the telegraph line as he went, allowing instant communication with General Halleck, and Secretary of War Stanton. Due to “unclear reports” from Pope, it was assumed that Beauregard’s Army was disintegrating; and the pursuit was terminated. In early June, Halleck got down to the business of rebuilding railroads (John Pope was in St. Louis contracting for rolling stock for Halleck’s railroad project when he received the call to “report to Washington.”)

Kristen

The above supplemental information was sent before I could add that your report on General John Pope accurately described Pope’s view of himself, disseminated to as many people in authority as possible.

Well Done!

Hi Mike, thanks for all the added info for everyone! As you know, I could not go too much beyond my theme of ‘counterinsurgency and Pope’. I appreciate you expanding beyond my post’s reach. Stay tuned for the next part of the post. I go into Pope and his policies in Virginia. Interesting stuff! Thanks for reading!

Kristen

Your excellent report describes “the John Pope” leaders in Washington thought they were getting (his reputation eagerly bolstered by a fawning Henry Halleck.) But, as we know, how we perceive ourselves, and how others perceive us… two different things. And reality is somewhere in between.

John Pope thought he was doing “a bang-up job.” Henry Halleck thought Pope was “his best commander” (above Grant, Thomas, Sherman, Rosecrans, Buell) and helped convince others of that belief. And the leaders in Washington were sold a Furphy.

All the best

Mike