Emerging Scholar Katelyn Brown

As part of our partnership with the American Civil War Museum in Richmond and Civil War Monitor, we’re pleased to introduce the next of our “Emerging Scholars,” Katelyn Brown. Katelyn will be presenting her work at the museum’s Grand Opening May 4.

As part of our partnership with the American Civil War Museum in Richmond and Civil War Monitor, we’re pleased to introduce the next of our “Emerging Scholars,” Katelyn Brown. Katelyn will be presenting her work at the museum’s Grand Opening May 4.

‘Literally Covered with Names’: Graffiti as a Historical Means of Expression

St. Augustine, Florida, is one of the oldest cities in the United States. Founded by Spanish explorers in 1565, the city has since been Spanish, English, American, and Confederate territory. Standing along the Matanzas River, adjacent to the city’s historic downtown area and old city gates is a fort, completed in 1695. This fort, called the Castillo de San Marcos, Fort St. Mark, and Fort Marion through the years depending on who held it, contains an incredible amount of history. Growing up, I had been there a few times. But it was not until recently that one aspect of the fort fully resonated with me: the graffiti that is carved into the walls within.[1]

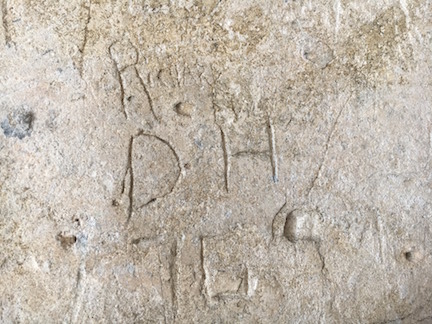

People tend to think of graffiti as a strictly modern thing. And at least for graffiti defined as spray painted tags and colorful imagery, it is. But more broadly defined, graffiti is also a carving or drawing of a word, name, or image on a public space, usually without permission, inspired by a human impulse which is as old as humanity (after all, what are cave drawings but a very early form of graffiti?). People throughout time have been inspired by blank walls.[2]

Prior to entering the fort in St. Augustine during a recent visit, I had thought a lot about graffiti as a part of my research on Civil War soldiers’ responses to death. Along with studio photographs of soldiers and drawings by soldiers, graffiti was a crucial part of my source base because I believed that it was an important, spontaneous outlet for men terrified both of dying and of being forgotten following death. Even today, churches, caverns, and houses throughout the South bear the names and drawings of soldiers inspired not just by blank walls, but also by fear.

Despite also being created by soldiers, the graffiti in the Castillo de San Marcos was different. Where Civil War soldiers had drawn women, political leaders, and scenes of warfare, the early soldiers of the fort had favored ships. Why the difference? The fort was largely isolated from both the colonial powers that owned it and from conflict. As a result, these soldiers, whether British or Spanish, were faced more with boredom than the brutal warfare of Civil War soldiers. For soldiers posted in a colony far from their homeland, the ships were likely a symbol of the land beyond the Matanzas River. For some, they may have meant freedom and adventure; for others they may have been the key to returning to Spain or England.[3]

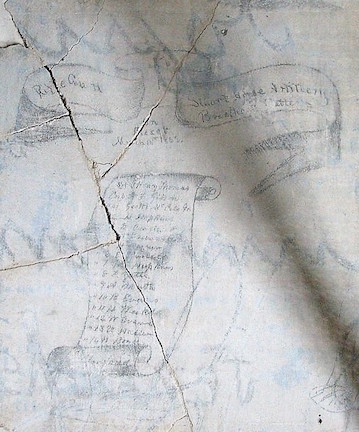

As men engaged in active warfare, Civil War soldiers were never far from the violence and issues of the war. As a result, the walls bear drawings of cannons, portraits of political leaders, and references to battles and other sites of the war. This immediacy also inspired soldiers to carve graffiti in a way that reflected a sense of camaraderie. One example of this can be seen in the “Maryland Scroll,” an elaborate carving made in the Graffiti House by Breathed’s Battery of Confederate Stuart Horse Artillery, who were passing through Brandy Station right before the Battle of Kelly’s Ford. This scroll contains the names of sixteen soldiers who chose to carve their names together, immortalizing not just their names and regiment, but also their bond as soldiers.[4]

While the subject matter of graffiti is interesting, my fascination for graffiti really came instead from its purpose. In particular, I was drawn to graffiti as soldiers’ attempts to find permanence amidst the death, destruction, and turmoil of the war. As one Civil War soldier summed it up, “in every direction the walls bear evidence of the desires of different individuals for immortality. They are literally covered with names…” Ultimately, the power of graffiti comes from its perceived ability to grant immortality by displaying a name and date for as long as the chosen surface lasts. It’s a way of speaking to future generations, saying “This is who I was. Remember me.” [5]

Today, there is one particular site that is doing exactly that: the “Graffiti House” at Brandy Station, Virginia, a house that bears the inscriptions of at least 30 identifiable signatures of soldiers from both sides. By viewing, studying, and photographing the graffiti that these soldiers created, visitors to the Graffiti House are granting those soldiers the immortality they sought. The House also goes one step farther, allowing visiting descendants of Civil War soldiers to write a tribute to their ancestors on the unmarked walls of the house. Following in the footsteps of Civil War soldiers themselves, these descendants are giving their ancestors a form of immortality, encouraging others to remember them and their service. [6] (Editor’s Note: For more on the Graffiti House and other sites that interpret Civil War graffiti, check out Paige Gibbons Backus’s Sept. 7, 2017 post on the Northern Virginia Graffiti Trail.)

My connection and response to the graffiti at the Castillo came from my increased awareness for the layers of history that surrounded not just the fort but also the act of graffitiing itself. In the Castillo, Spanish ships are carved into the walls alongside names of soldiers from the 1750s, paint dating back to the 1600s, cultural symbols made by Native people who had been imprisoned there through the 19th century, and names of tourists who visited in the 1910s. Similarly, the inscriptions of Civil War soldiers alongside their descendants’ in the Graffiti House reminds me that these sites are giant time capsules, full of the markings of people dreaming of home, seeking immortality, or who were simply inspired by the history they could feel around them. Ultimately, whether these people lived in 17th-century Florida, 19th-century Virginia, or today, graffiti offers a powerful means of expression, linking humans together across centuries and enlightening us today about not only our own connections to the past, but also our hopes and desires for the future. [7]

————

About Katelyn Brown

Katelyn Brown is a military brat from Tampa, Florida. Despite moving frequently as a child, her father took her to every local battlefield he could find, inspiring a life-long love of history.

Despite initially attending Christopher Newport University for economics, Brown rekindled her love for history and particularly the Civil War in the on-campus archives of The Mariners’ Museum. This time in the archives convinced her to pursue an American Studies degree while at CNU and a history graduate degree after graduation. In 2016, she moved to Blacksburg to attend Virginia Tech’s Master’s in History program. While at Tech, she worked as a graduate assistant in Special Collections and as a teaching and research assistant for the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies.

Her thesis research is on the ways that Civil War soldiers use visual culture as a means of finding permanence in the face of death. She has also published work on African American soldiers and Civil War photography. She now works as program coordinator for the Virginia Center for Civil War Studies and as an independent contractor for the American Battlefield Trust.

————

Citations

[1] National Park Service, Castillo de San Marcos (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2017).

[2] “Graffiti,” English Oxford Dictionaries, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/graffiti.

[3] While the soldiers who manned the Castillo were isolated and most days were uneventful, they were not completely unimpacted by conflict. Throughout its history, the fort has withstood two sieges and a few raids that would have placed the soldiers inside in danger similar to that experienced by Civil War soldiers. Unfortunately, it is impossible to say what, if any, graffiti was created as a result of these situations. National Park Service, Virtual Tour, PowerPoint presentation, last modified May 4, 2016, https://www.nps.gov/casa/learn/photosmultimedia/virtualtour.htm.

[4] “Soldiers and Graffiti,” Brandy Station Foundation, http://www.brandystationfoundation.com/

[5] Letter by unnamed soldier quoted in Bradley Gernard, A Virginia Village Goes to War: Falls Church During the Civil War (Virginia Beach, VA: The Donning Company, 2002), 124.

[6] Derek H. Alderman and Terri Moreau, “Graffiti Heritage: Civil War Memory in Virginia,” in Geography and Memory: Explorations in Identity, Place and Becoming, ed. Owain Jones and Joanne Garde-Hansen (London: Palgrave Macmillion, 2012), 139.

[7] Unfortunately, the graffiti already in place in the fort has inspired modern tourists to make their mark, as well, behavior which is not allowed at the Castillo or at most historic sites. The Graffiti House’s allowance of writing on the walls is unique. In most other cases, the creation of modern graffiti on historic sites or artifacts is destructive and is condemned.

There’s a church on the east end of the Isle d’Orleans in the St. Lawrence River just outside of Quebec City where the graffiti of British soldiers who were about to fight the French on the Plains of Abraham in 1759 is preserved.