The Surprises in William Hoffman’s Photo

I’ve been working on Derek Maxfield’s upcoming ECWS book on the prison camp in Elmira New York, Hellmira, and I came across something fun while prepping the photos for layout.

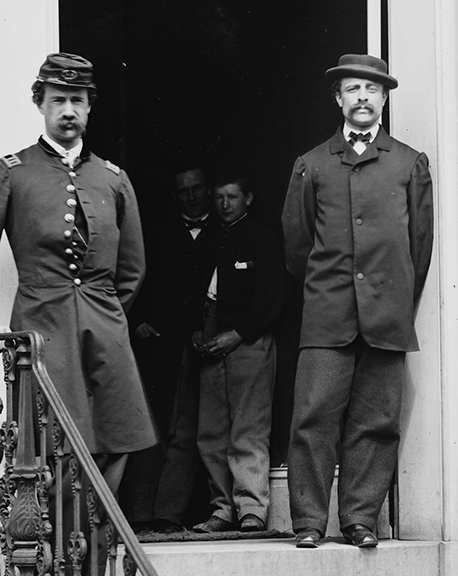

The photo in question: “Washington, D.C. Gen. William Hoffman, Commissary General of Prisoners (at right) and staff on steps of office, F. St. at 20th NW.”

Hoffman, effective but frugal to the point of deprivation, had a lead role in overseeing Union POW camps during the Civil War.

In our ECWS books, when we identify a main character, we’ll usually include his or her mugshot: one of the typical head-and-shoulders studio portraits we’re all so familiar with. Such images serve their purpose perfectly by clearly showing a reader what a person looked like.

But because we use so many mugshots, I’m always glad to consider something a little different, such as this photo of Hoffman. Readers don’t get to see Hoffman’s face as clearly as they would in a typical mugshot, but seeing him posed in his own environment gives us something different to look at. It makes a photo more visually engaging precisely because it’s not like all the others.

But what’s also cool about photos like this are the things going on in the background. Yes, it’s a photo of Hoffman and his staff, but what else is in the picture?

This is something my friend Garry Adelman helped me better appreciate. Garry is a co-founder of the Center for Civil War Photography, and he loves Civil War photos (and that’s probably not a strong-enough word to describe it). Garry has done a lot to help me see photos more fully.

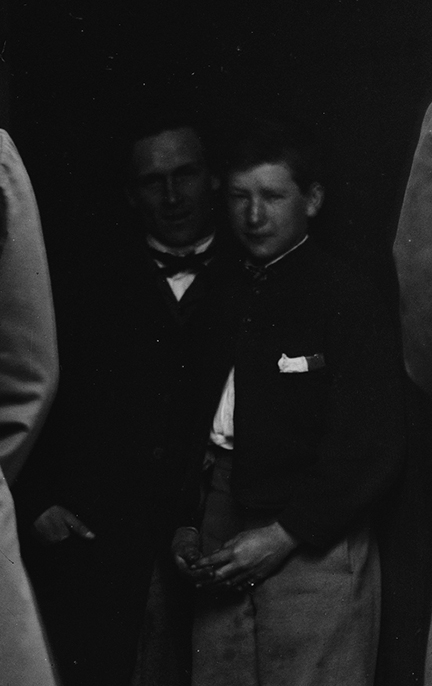

Because glass plate negatives provided an incredible level of resolution, Civil War photos can be so crisp and clear you can literally see the lines on people’s hands if you zoom in close enough to a high-res image.

In the case of Hoffman, we can read the letters of the sign on the wall behind him. We can see hiss long hair, curled around his ears. We can see the Santa-like beard that whips at its very end from left to right. We can see an expression in the eyes that might be hang-dog, might be squinting into the sun. And what is Hoffman holding in his right hand?

What drew my attention next were the figures flanking the doorway:

Certainly the men standing on the top stoop look like they belong in the photo, posing for the camera like Hoffman. The officer on the left has his jacket partially unbuttoned as though ready to stick his right hand Napoleon-like inside (as Hoffman does, too). But knowing they were being photographed, why didn’t they strike the usual Napoleonic pose? Meanwhile, the man on the right, apparently a civilian, wears his hat at a jaunty angle and has arched his left eyebrow as if to say, “Dashing, aren’t I?”

And check out the people standing in the shadows inside the doorframe. Who are they, lurking there in semi darkness?

But even better: look closely at the window behind Hoffman. Some guy is photo bombing him!

We can look so closely that we can even see the reflection of another face on the window pane, obscuring this man’s mouth almost the way a beard might. We can see the hinges on the windows. We can see a wedding ring on the man’s finger.

In the end, this has little to do with Elmira. But it’s a great reminder of the power of Civil War photographs as tools for helping us learn and see—and sometimes making us wonder. I’ll never know the stories of the mysterious shadow men or the photo bomber, but knowing they’re there makes part of my day a little cooler.

You can see a high-res version of this photo for yourself at the Library of Congress by clicking here.

Born in 1807, William Hoffman was a graduate of the same West Point Class of 1829 as Joseph Johnston and Robert E. Lee. But Hoffman was not as sharp as Johnston or Lee, and was relegated to a support role during the Civil War: the Northern counterpart to John H. Winder, Confederate Commissioner of Prison Camps.

With the death rate in Northern and Southern prisons about equal during the war, it could be argued that Winder and Hoffman performed equally badly, except… Brigadier General Hoffman also managed the Northern Parole Camps (a nightmare concocted by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, that confined Union soldiers recently released from Southern prisons until they were “properly exchanged.”) Hundreds, perhaps as many as two thousand, Union soldiers died in the Parole camps operated at Portsmouth, Rhode Island, Benton Barracks, Missouri and Annapolis, Maryland. All for the sake of control (it was feared the recently released Paroled prisoners would not return to their regiments, if permitted to go home until exchanged.)

Although the South is said to have experimented with Parole camps, it was an experiment that they quickly abandoned.

William Hoffman had his own unfortunate experience early in the war as “Guest of the Confederacy.” He died in 1884 and is buried in Chippiannock Cemetery, Rock Island County, Illinois.

A great-great grandfather was captured and interred in Libby Prison. I have wondered if he spent time in Parole, Annapolis MD after he was exchanged. His pension application mentions Libby but nothing about his exchange/parole process.

Norma Belt

Two other Parole camps used by the Union were at Camp Chase, Ohio and Camp Elder, Pennsylvania. Paroled prisoners held at Benton Barracks often had “BB” indicated on their records. Annapolis is clearly marked (if a Paroled prisoner was there confined) on records obtained from NARA (Union Soldier Compiled Service Records.) A good source that lists most, but not all, Union soldiers held as POW in the South (including time spent in Parole camp, if applicable)

http://www.civilwarprisoners.com/search.php?database=cahaba

[Need to insert Last Name and regiment of soldier. Or try inserting only the regiment (for example, 12th Iowa) and get the listing of POWs for the entire regiment.] If no result during search for soldier, try different spellings of his Last Name.

Cheers

Mike Maxwell

Chris,

The house–now called the F Street House–still stands and is one of the last remaining antebellum houses in the neighborhood. I worked around the corner from the house for three years and it currently is being used as the residence for the President of The George Washington University. When it served as GW’s Alumni House from 2000-2008, I spent much time exploring the interior and comparing the wartime photos with the current exterior.

Besides from a modern paint job over the original brick and being elevated from the street now, not much has changed. One can still imagine General Hoffman standing out front. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/F_Street_House

Additionally, one of the houses that William Seward lived in during the 1850s stands nearby and General Henry Hunt’s postwar residence was being used as a frat house. Foggy Bottom still has some Civil War history remaining.