History in Pieces

History comes in many pieces. My good friend Hal, a retired navy captain, collects Civil War naval artifacts. He acquired items that caught his eye over the years without any particular theme in mind only to find threads and connections that tell fascinating stories. Here are some of them.

History comes in many pieces. My good friend Hal, a retired navy captain, collects Civil War naval artifacts. He acquired items that caught his eye over the years without any particular theme in mind only to find threads and connections that tell fascinating stories. Here are some of them.

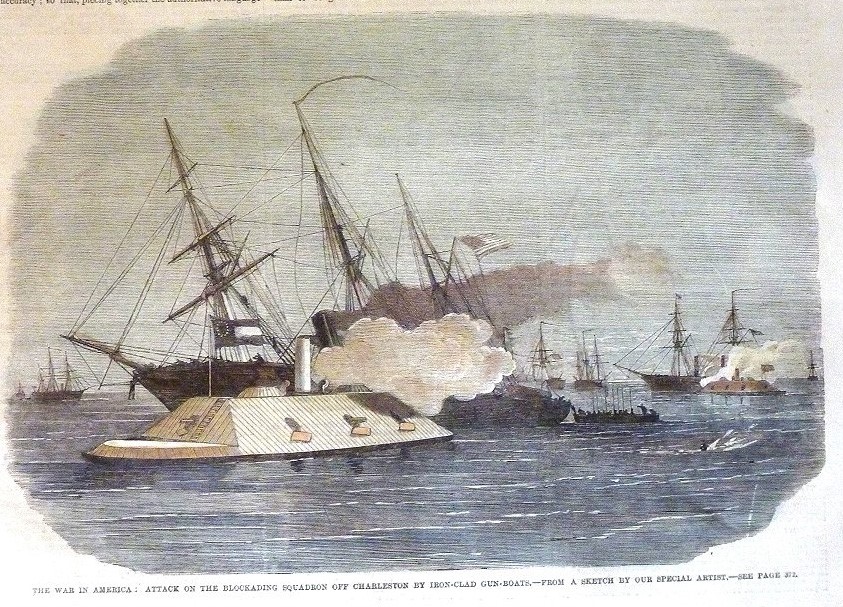

Before dawn on January 31st, 1863, Confederate ironclads CSS Palmetto State and CSS Chicora slipped out of Charleston harbor in thick haze to attack Union blockaders. Palmetto State snuck up to the gunboat USS Mercedita, fired a gun into and rammed her, ripping a hole in the hull and piercing the boiler, which blew up. Apparently sinking, Mercedita struck her colors.

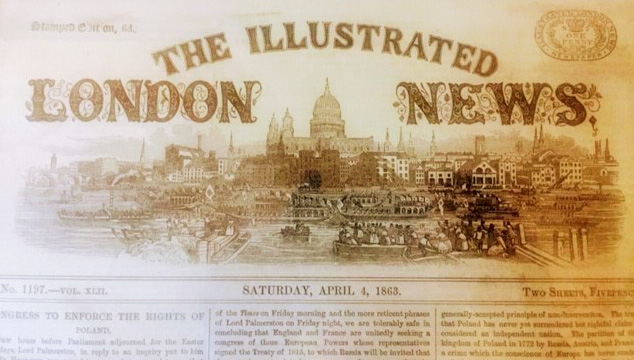

Hal’s framed front-page copy of The Illustrated London News contains a story and illustration of the encounter. The News was the world’s first illustrated weekly (1842-2003). During the war, it responded to British readers ravenous for—frequently inaccurate—war news and detailed wood-block prints. This copy was obtained from a map/print dealer in England who hand-colored the illustration.

Palmetto State accepted parole from surrendered Federals on Mercedita and chugged off with Chicora after more blockaders, thinking to return later and reclaim her prize. Mercedita’s captain promptly broke parole, affected temporary repairs, and fled with his ship.

Palmetto State accepted parole from surrendered Federals on Mercedita and chugged off with Chicora after more blockaders, thinking to return later and reclaim her prize. Mercedita’s captain promptly broke parole, affected temporary repairs, and fled with his ship.

Palmetto State went next for the USS Keystone State. The Yankee dodged the ram but was seriously damaged by her guns and had to be towed to safety. Palmetto State and her partner, Chicora, were standard Confederate casemate ironclads built in Charleston.

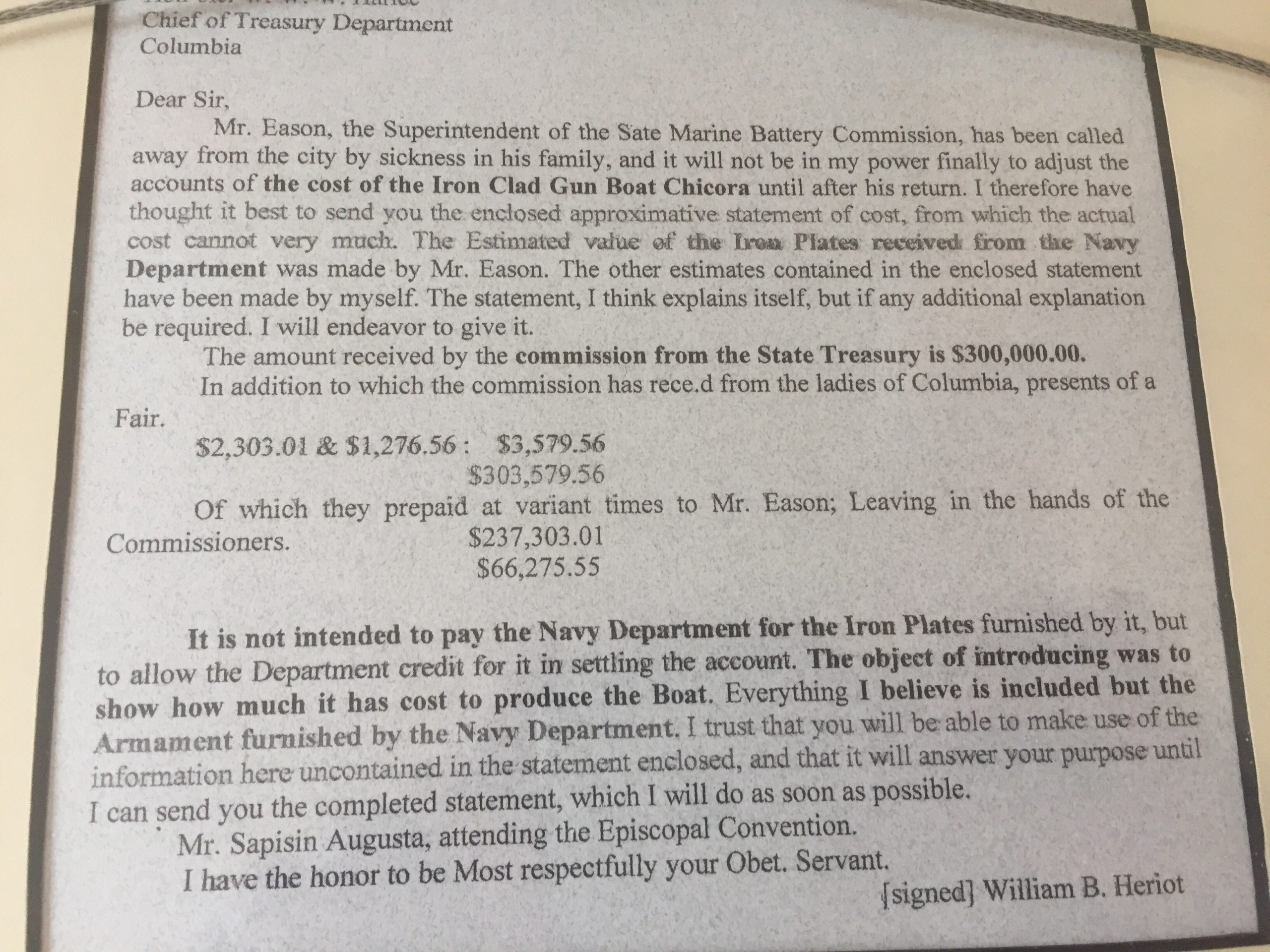

The next artifact is the financing letter (page 2) for Chicora’s construction in 1862 with a transcription. Funds were provided to the Treasurer of the Confederate Navy by the State of South Carolina and the Ladies of Columbia, South Carolina. About $300,000 funded the ship, less the iron cladding.

The following shows an early 1900’s postcard of Chicora franked with a newly issued postage stamp, bearing the postmark of the first day of issue and the officially chosen place of issue. In philatelic terms, a “first day cover.”

The following shows an early 1900’s postcard of Chicora franked with a newly issued postage stamp, bearing the postmark of the first day of issue and the officially chosen place of issue. In philatelic terms, a “first day cover.”

On that day, Chicora and Palmetto State continued long-range gunnery duals with other Union vessels, damaging a few, before being chased back to harbor by rapidly converging warships, including the USS Housatonic. Thereafter, the ironclads defended Charleston only to be destroyed by their own crews when the city was evacuated in February 1865.

On that day, Chicora and Palmetto State continued long-range gunnery duals with other Union vessels, damaging a few, before being chased back to harbor by rapidly converging warships, including the USS Housatonic. Thereafter, the ironclads defended Charleston only to be destroyed by their own crews when the city was evacuated in February 1865.

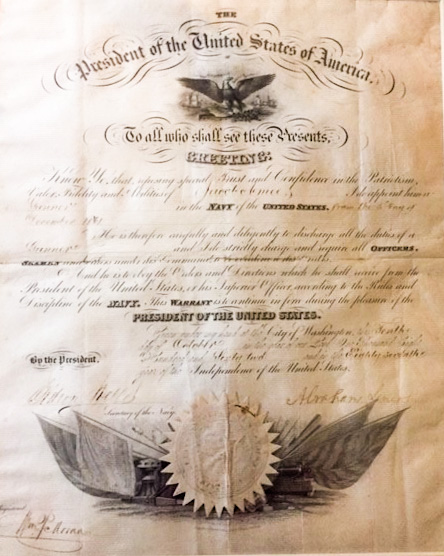

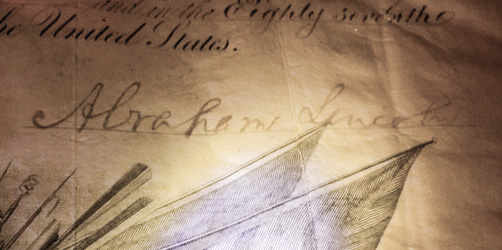

The USS Mercedita did not escape the encounter without casualties. Shrapnel from the exploding boiler penetrated a stateroom and killed gunnery officer Jacob Amee. Below is Amee’s framed commission as an officer of the U.S. Navy signed by Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles just three months earlier.

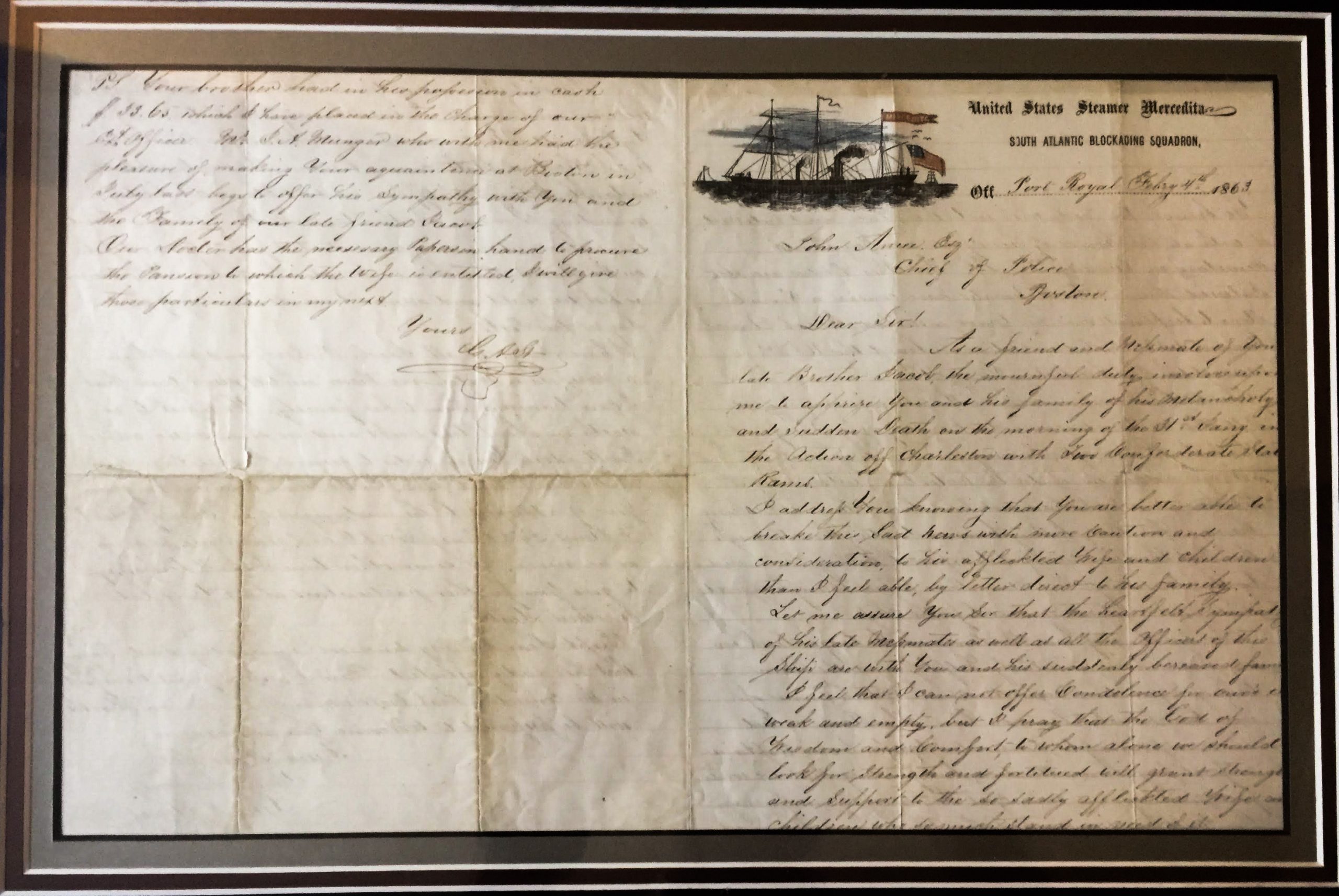

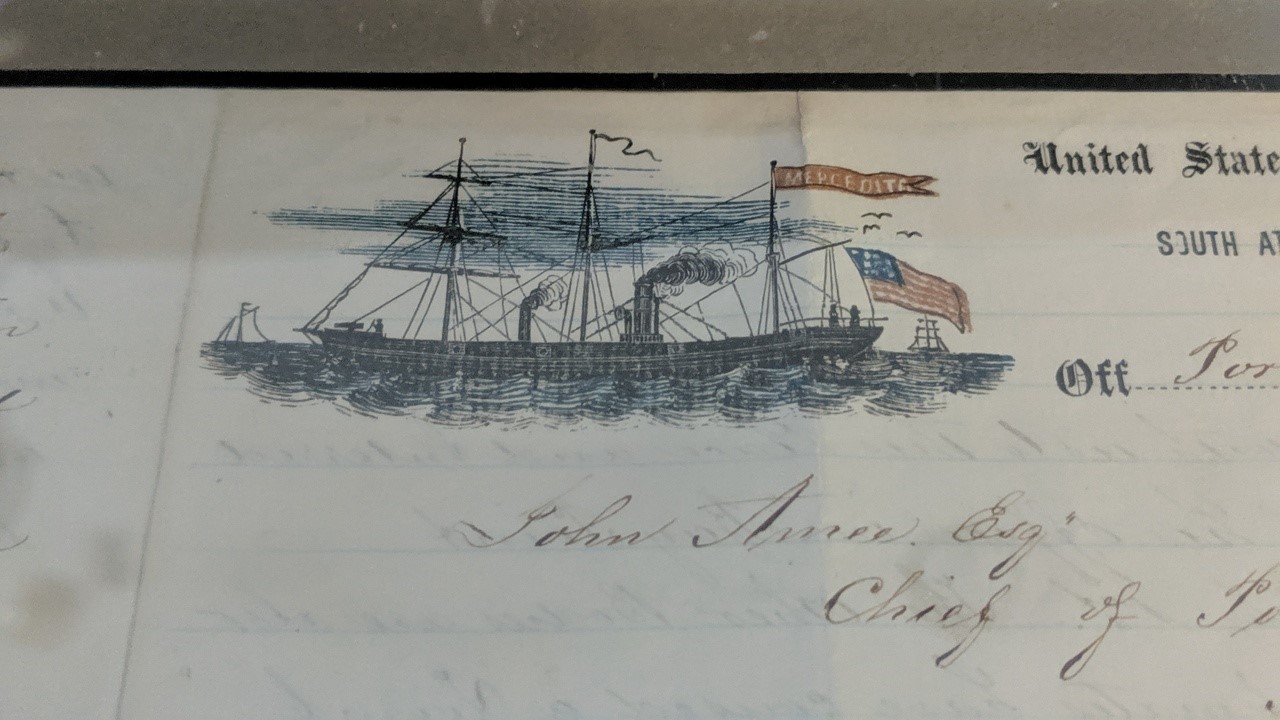

Next is a letter from Mercedita’s captain to Amee’s next of kin describing the attack, his burial in Port Royal, South Carolina, and disposition of his belongings. It’s four pages are on ship’s stationary with a color picture of Mercedita and the imprint “South Atlantic Blockade Squadron.” The letter is addressed to Josiah Amee, Chief of Police, Boston, Mass.

Earlier in 1862, Mercedita had intercepted the Rebel blockade runner Bermuda. Among the cargo removed from her were cases of watermarked British paper in route to the Confederacy for bank note printing. One framed piece is shown here. The paper ended up in Philadelphia for printing as some form of tinder, but not U.S. bank notes. Mercedita continued to serve the blockade until decommissioned and sold in October 1865.

The powerful sloop-of-war USS Housatonic had been among the warships that chased Chicora and Palmetto State back into port. She spent most of the war blockading Charleston. On March 19, 1863, Housatonic engaged in a running gun battle with the British blockade runner Georgiana until she ran ashore on Long Island, a total loss.

Georgiana was a powerful, fast, iron-hulled vessel. Speculation was she would be fitted out as a deadly commerce raider like the CSS Alabama, Florida, and Shenandoah. The huge cargo of munitions, medicine and merchandise was valued at over $1,000,000.

The wreck was discovered in 1965 in shallow water and is now a popular diving site. Large hull sections are still visible along with heavily encrusted artifacts in the hold where they have lain for over 150 years. Some items have been recovered. This picture shows Hal’s chunk of concreted ivory buttons, some pins, Enfield bullets, and an ink well.

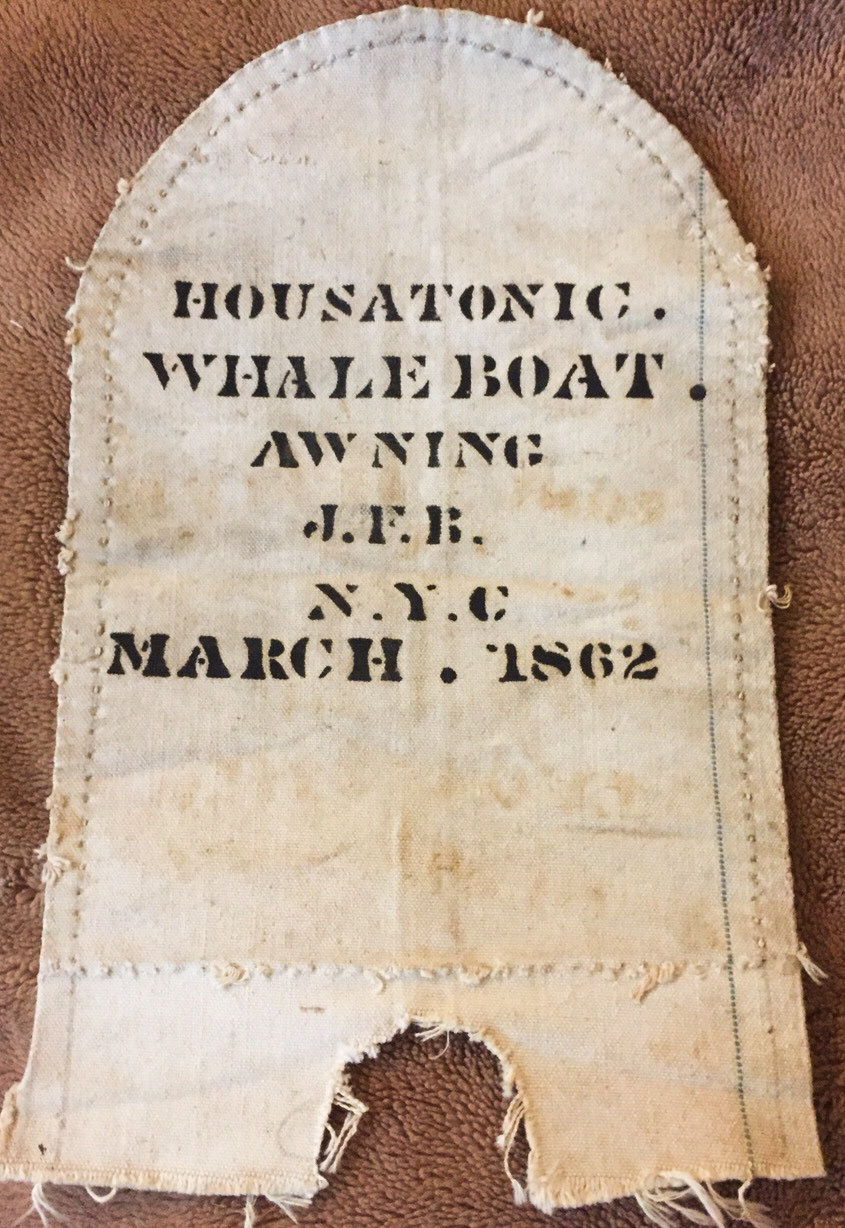

The following artifact in Hal’s collection is a framed 14- by 9- inch piece of stenciled canvas, part of a boat awning probably supplied to the USS Housatonic when she was equipped and commissioned in August 1862.

Framed with the piece of canvas is a hand-written note by Confederate soldier William Mason Smith.

How and when Housatonic‘s whaleboat was “captured” in the action referred to in Smith’s note is unknown. On April 7, 1863, the Union navy undertook the only major, but unsuccessful, assault on Charleston harbor and Fort Sumter primarily with ironclads. Housatonic was in the backup fleet but did not play a major role.

However, Housatonic‘s boats, with howitzers mounted in the bows, also supported the attack on Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor on 10-11 July 1863. And they participated throughout the summer in continuing patrols close ashore, troop landings, raids, and shelling of Southern works, probably including Fort Sumter. One or more boats could have been lost to the Rebels during these operations. On February 17, 1864, Housatonic became the first warship sunk by a submarine, the CSS Hunley, outside Charleston Harbor.

An accompanying inscription states that William Mason Smith was born July 18th, 1843 in Charleston, served in the 27th South Carolina infantry, was wounded at Cold Harbor in June 1864, and died in Richmond August 18. His family home on Meeting Street is one of Charleston’s historically preserved homes.

All the above are tangible reminders of untold stories, countless routine details, and humble participants in momentous events. They bring us closer to history, and Hal is still collecting.

1 Response to History in Pieces