The Emergency Ironclads

In late summer 1861, the United States Navy initiated a crash program to build their first ironclad warships, leading directly to the titanic clash between the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia (ex USS Merrimack) in Hampton Roads on March 9, 1862. One might assume that the primary impetus behind this new naval strategy was to counter Rebel ironclads like Virginia. That would be incorrect.

“Much attention has been given within the last few years to the subject of floating batteries, or iron-clad steamers,” Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles reported to Congress in July. “The ingenuity and inventive faculties of our own countrymen have also been stimulated by recent occurrences.”

It was, however, a subject full of difficulty and doubt. Large-scale experiments in England and France had limited success. “Yet it was evident that a new and material element in maritime warfare was developing itself, and demanded immediate attention.”[1]

The secretary was overseeing an urgent, immense, unprecedented warship procurement and building program while instigating a nearly impossible, continent-wide blockade.

It would not be advisable in the current crisis, Welles advised, to commit heavy expenditures for experiments on unproven technology.

He drafted a bill authorizing appointment of a “proper and competent board” to report on the subject before Congress considered larger appropriations for operational vessels.[2]

A “distinguished citizen of Massachusetts” entered a letter into the Congressional record supporting the Welles legislation. Mr. E. H. Derby urged the necessity for acquiring “mail-clad steamers—a subject which he has thoroughly examined.” Neglect of this opportunity “will expose us to serious losses, obloquy, and disgrace.” The British had tested and confirmed that 4.5-inch iron plates were impervious to shot and shell even from the best Armstrong and Whitworth 100-pounder cannon. They had ceased building wooden warships altogether.

“England and France will, by the close of this year, have twenty to thirty iron-clad steam ships, each of which could pass into Boston or New York with impunity, and possibly destroy either city. Unless we have means to meet them, France and England may be able to dictate terms as to the southern blockade. With such steamers we can, with little or no loss, recover Charleston, Savannah, Pensacola, Galveston, Mobile, and New Orleans…. [I] trust you will grasp a weapon so essential to our country at this moment.”[3]

Iowa Senator James Grimes introduced the bill: “We need a more effective blockade…. Scoundrels North, as well as scoundrels South, are carrying on an unlawful trade in fraud of our revenue.” Pirates and sea rovers must be captured; Southern harbors and forts must be retaken; commerce must be protected, and Northern harbors defended.

“Suppose England, in her love for cotton, should forget the duties which she owes to mankind and attempt to break our blockade, and we should get into trouble with her: what is to become of our northern cities and our cities upon the coast?” Grimes wished to protect his country and “preserve it in all its parts.” The threat was real and would far outlast the–presumably short–rebellion. [4]

Navies on both sides of the Atlantic had grappled for decades with simultaneous revolutions in warship construction, propulsion, and armament. In 1855, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis dispatched an army commission including then Capt. George McClellan to observe the Crimean War. They witnessed the siege of Sevastopol and reported in engineering detail as British and French ironclad floating batteries, mortar vessels, and gunboats reduced Russian forts at Kinburn to rubble while easily deflecting savage return fire from heavy shore guns.

The report’s conclusion: “Steam-propelling power, the rifle cannon, long range and heavy caliber, in wrought-iron vessels, are the new features…. It is the bounden duty of the officers of our army and navy to study this branch of the art of war….” Wooden warships dependent on wind, armed with lighter smoothbores, had never been effective against stout walls. But now, the United States must improve shore fortifications and must devise “floating armament” to drive future ironclad invaders from national waters.[5]

Europeans struggled to produce armored vessels that could sail, steam, and fight in open seas. France led the way in 1859 with the impressive ironclad frigate La Gloire, followed in 1860 by the magnificent British HMS Warrior, an all-iron vessel representing the epitome of contemporary naval engineering.

These prototypes had serious shortcomings: high cost, limited cruising range, frequent industrial maintenance. Wooden hulls of equal displacement were lighter, generally faster, more flexible and survivable in heavy seas, and not as susceptible to rust and fouling. Contemporary iron was subject to inconsistencies in manufacturing processes and ingredients. Bad iron could be as brittle, splintering, and fatal under fire as wood, perhaps more so.

The U.S. Navy had been in the forefront of developments in steam propulsion and naval armaments. The 1840s and 1850s saw a vigorous program of modernization and new construction, much of it sponsored by Senator Stephen R. Mallory of Florida, chairman of the Committee on Naval Affairs—and future Confederate Secretary of the Navy.

But the rising generation of technically savvy American naval officers had been content to allow Europeans to pursue costly experiments in armor protection. In America, wood was inexpensive and plentiful; iron was expensive and difficult to produce, the reverse of Great Britain. Public and Congressional disinterest generated limited funding.

The United States had little incentive to build a large seagoing force—no far-flung empire to defend, no neighboring menace, and until recently, no imminent danger from across the Atlantic. Naval strategy focused on harbor and coastal defense with a requisite number of fast cruisers to protect commerce in distant waters.

Secession altered the strategic seascape dramatically as crisis rippled across the ocean. Britons experienced economic and commercial disruptions, and massive unemployment in the textile mills leading to domestic unrest and political turmoil.

Conflicts flared over the rights and duties of neutrals, the blockade, trade in arms, munitions and warships, privateering and commerce raiding. Echoing the Revolution and War of 1812, old enmities resurfaced on both sides. British leaders seriously considered intervention, with force if necessary, to protect national interests. They came close to recognizing the Confederacy, potentially changing the course of the conflict.

The specter of a third war between the United States and the world’s most powerful nation—now armed with big, seagoing ironclads—became immediate. The Philadelphia Examiner reflected an aroused Northern public opinion when the editors thought it curious that the United States should be behind the age. “If we intend to have a national naval force worthy of our power and pretensions, we shall have to…build iron-cased vessels, as France and England have done, and are doing.”[6]

Congress passed and President Lincoln signed the Welles legislation on August 3, 1861. As recommended, it directed the secretary to appoint an “Ironclad Board” of naval officers to investigate plans and specifications for constructing “iron or steel-clad steamships or steam batteries” and upon their recommendation, to cause one or more prototypes to be built. The act appropriated for that purpose $1.5M.[7]

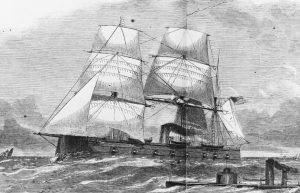

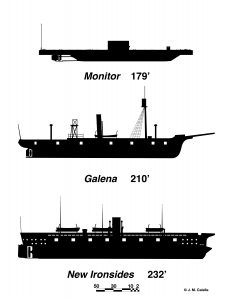

Given the urgency, the board took the radical step of recommending three designs to be produced simultaneously on a spectrum of increasing risk. The most conservative and most practicable featured a fully seaworthy, wooden-hulled sailing vessel with iron plating, auxiliary steam engine, and broadside battery. Conceptually like Gloire and Warrior, the future USS New Ironsides traded higher cost and longer construction time for lower technological uncertainty while countering the foreign ironclad threat.

The second design also was a conventional sail/steam frigate but smaller, shallower draft, and armored with interlocking strips of wrought iron in a manner not yet tried. She would become the USS Galena.

The final board selection was a leap in the dark.

Swedish engineer John Ericsson produced plans for “a floating battery absolutely impregnable to the heaviest shot or shell.”

Ericsson’s influential friend and sponsor, Cornelius S. Bushnell, took the plans to Washington. They included a pasteboard model of a small iron raft with—its most radical innovation—a revolving turret enclosing a tiny cannon. The idea percolating in Ericsson’s mind for years was inspired by Swedish timber rafts.[8]

President Lincoln, ever fascinated by gadgets, “was at once greatly pleased with the simplicity of the plan,” wrote Bushnell. “All [board members] were surprised at the novelty of the plan. Some advised trying it; others ridiculed it.” The president remarked: “All I have to say is what the girl said when she put her foot into the stocking, ‘It strikes me there’s something in it.’” [9]

With Secretary Welles’s encouragement, the reluctant officers of the board succumbed to persuasion. Ericsson’s plan addressed the immediate requirement: a combat-ready craft suitable for restricted waters to be rapidly constructed and deployed against Virginia.

In its favor were presumed invulnerability, small size, shallow draft, and limited exposed target area. Worrisome unknowns included: over reliance on steam power, semi-submerged hull, questionable stability, and untried turret-mounted armament. It was still an “experiment.”

The USS Monitor repulsed the CSS Virginia in Hampton Roads and shook the world. But Monitor was not so much revolutionary as an ingenious assemblage and dramatic demonstration of emerging technologies under development in the small international community of naval engineers.

The USS New Ironsides was effective as a sea-going blockader and shore bombardment platform, potentially capable of countering European ironclads. The smaller and more lightly armored USS Galena was less successful, taking a severe battering at the battle of Drewry’s Bluff on the James River in May 1862.

Fortunately, the ironclad threat from over the pond never materialized as Great Britain and France wisely stayed out of the conflict.

Adapted from Dwight’s new book, Unlike Anything that Ever Floated: The Monitor and Virginia and the Battle of Hampton Roads, March 8-9, 1862 coming soon from Savas Beatie for the Emerging Civil War Public History Series.

[1] “From the report of the Secretary of the Navy, July 4, 1861,” in Report of the Secretary of the Navy in Relation to Armored Vessels (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1864), 1. Hereafter cited as Report…Armored Vessels; “From the report of the Secretary of the Navy, December 1, 1862,” Report. . .Armored Vessels, 8.

[2] “From the report of the Secretary of the Navy, July 4, 1861,” Report…Armored Vessels, 1.

[3] John C. Rives, The Congressional Globe: The Debates and Proceedings of the First Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress (Washington, 1861), 210.

[4] Rives, Congressional Globe, 256-57.

[5] Major Richard Delafield, Report on the Art of War in Europe, 1854, 1855, and 1856 (Washington, 1860), 176.

[6] Philadelphia Examiner, March 21, 1861, in David A. Mindell, Iron Coffin: War, Technology, and Experience aboard the USS Monitor, Updated Edition (Baltimore, 2012), loc. 658 of 4524, Kindle.

[7] “Act of Congress authorizing the construction of iron-clad vessels,” Report…Armored Vessels, 1-2.

[8] C. S. Bushnell, “Negotiations for the Building of the ‘Monitor,’” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Being for The Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon “The Century War Series.” Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, of the Editorial Staff of “The Century Magazine,” 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), vol. 1, 748.

[9] C. S. Bushnell, “Negotiations for the Building of the ‘Monitor,’” 749.

Dwight, I would love to see you write a similar article on why and how the north created armored gunboats for use on the western waters of the United States

Thanks for your interest, Bryce. I talked about that in previous posts. Pease see

Unvexed Waters: Mississippi River Squadron, Parts I and 2. Here is the link:

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2018/06/04/unvexed-waters-mississippi-river-squadron-part-i/

Or you can type “unvexed waters” in the ECW Archives search box at the top right of this screen.

This is a subject I know little on, so I find you article intriguing Dwight, thanks. I’ve seen Old Ironsides, the Flagship Niagara in Erie, Pa and the remnants of the CSS Neuse, but wish there was a full fledged Civil War ironclad out there to tour. Portsmouth is on my bucket list. Perhaps I’ll check out one of your books here soon.

Matthew: The closest you can get to touring an ironclad is the USS Monitor Center at the The Mariners’ Museum & Park in Newport News, VA (https://www.monitorcenter.org/). Great place! If you are ever out west, check the USS Cairo Gunboat and Museum in Vicksburg (https://www.nps.gov/vick/u-s-s-cairo-gunboat.htm).

As a retired Engineering Duty officer, two books I find essential:

Civil War Ironclads

The U.S. Navy and Industrial Mobilization

William H Roberts 2003

Naval Engineering and American Sea Power

American Society of Naval Engineers (Randolph W. King editor) 1989

Thanks, Scott. The Roberts book was very helpful in my research, but haven’t seen the other. Will take a look.