Face of Battle: Responding to Fear

Michael Flynn (Lt. Gen. USA. Ret.) recently published a message meant to encourage American citizens as we go through these traumatic times. One thing he said reminded me of conversations I have had with my combat veteran friends. “Let us not fear the uncertainty that comes with the unknown, instead accept it and fight through that sense of fear.”[1] Why should we fight through fear? Some believe it is a biblical and sound military mandate. Others see it as a useful principle. No matter their religious background, the veterans I know noted having to push their fears to the back of their mind in order to maintain their composure. It was not easy, but keeping calm allowed them to critically think, react, and survive. So, let’s examine how Civil War Soldiers responded to their fear in battle and the consequences of their reactions.[2]

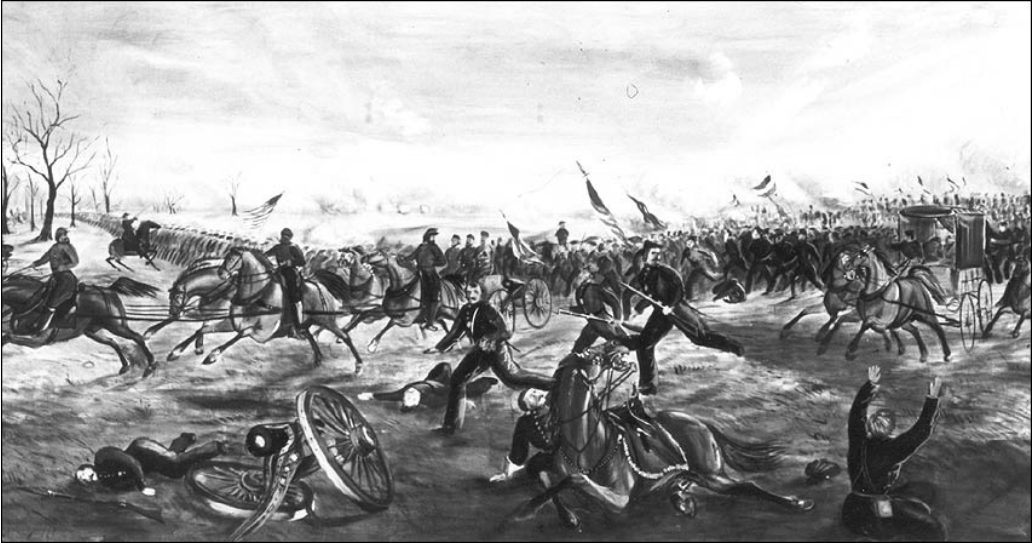

Uncontrolled fear turns to panic and spreads like wild-fire. When this occurred, one-of-two results enfolded. If leadership was unwilling or unable to control the terrified troops, entire armies collapsed. The earliest and most famous incident was the Union army’s great skedaddle from Manassas, Virginia, to Washington City after the First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run), July 21, 1861. Three months later, another Union force was trounced at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, October 21, 1861. Southern armies had their panic-stricken moments as well. One Confederate rout occurred at Cedar Creek, Virginia, October 19, 1864. It was a pivotal loss as it went a long way toward President Abraham Lincoln’s re-election. Another strategic defeat transpired on the second day of the Battle of Nashville, December 16, 1864. After the Confederate left flank broke, panic swept through all the ranks in line of battle. The entire force was soon in full retreat, and it never regained its effective fighting capability.[3]

Uncontrolled fear turns to panic and spreads like wild-fire. When this occurred, one-of-two results enfolded. If leadership was unwilling or unable to control the terrified troops, entire armies collapsed. The earliest and most famous incident was the Union army’s great skedaddle from Manassas, Virginia, to Washington City after the First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run), July 21, 1861. Three months later, another Union force was trounced at the Battle of Ball’s Bluff, October 21, 1861. Southern armies had their panic-stricken moments as well. One Confederate rout occurred at Cedar Creek, Virginia, October 19, 1864. It was a pivotal loss as it went a long way toward President Abraham Lincoln’s re-election. Another strategic defeat transpired on the second day of the Battle of Nashville, December 16, 1864. After the Confederate left flank broke, panic swept through all the ranks in line of battle. The entire force was soon in full retreat, and it never regained its effective fighting capability.[3]

Now, in cases where officers and senior enlisted controlled the effects of panic and rallied their men, the outcome was much better. In one incident during the Battle of Murfreesboro (Stones River), Tennessee, December 31, 1862 to January 2, 1863, a volunteer Union brigade and some U.S. Regulars found themselves isolated. The Regulars broke first and ran through the volunteers “flying in wild disorder . . . hotly pursued by enemy.” The volunteer brigade soon followed, running “like hell.”[4] The day was only saved when Union officers and senior enlisted calmed the men down, reformed their lines, and readied them to face the enemy once again.[5] Many a Confederate leader had to regroup his terrified men, including senior commanders. On May 12, 1864, during the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, General R. E. Lee rallied and reorganized his troops who were fleeing to the rear. This quick reaction prevented his army from completely collapsing.[6]

Now, in cases where officers and senior enlisted controlled the effects of panic and rallied their men, the outcome was much better. In one incident during the Battle of Murfreesboro (Stones River), Tennessee, December 31, 1862 to January 2, 1863, a volunteer Union brigade and some U.S. Regulars found themselves isolated. The Regulars broke first and ran through the volunteers “flying in wild disorder . . . hotly pursued by enemy.” The volunteer brigade soon followed, running “like hell.”[4] The day was only saved when Union officers and senior enlisted calmed the men down, reformed their lines, and readied them to face the enemy once again.[5] Many a Confederate leader had to regroup his terrified men, including senior commanders. On May 12, 1864, during the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, General R. E. Lee rallied and reorganized his troops who were fleeing to the rear. This quick reaction prevented his army from completely collapsing.[6]

Although formations usually kept men in close contact, sometimes uncontrolled fear only affected single individuals. In these cases, a Soldier might commit an act of cowardice such as abandoning his comrades during a battle. Many considered this the ultimate “sin” that was unpardonable “either in this world or the next.”[7] Soldiers committed these cowardly acts in various ways with various results. Some got away with disappearing before a battle and reappearing afterward with the excuse he had been ordered to guard supplies.[8] Others waited to disappear under cover of the smoky haze of battle. An Alabama sergeant caught one of his privates slinking away during the fighting near Little Round Top, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, July 2, 1863. The sergeant grabbed the private by the collar and forced him to fire and load. When the private was shot and killed, the sergeant threw him to the ground. Sergeants in the 9th New Jersey were just as tough. In 1864, one noted those conscripts or substitutes who attempted to desert their post during battle came under fire from the “front and rear” because the veterans in the regiment shot “cowards from their own ranks . . . .” How many officers or sergeants killed their men for the act of cowardice? There is no way of knowing; it was not a subject widely discussed.[9]

Most Soldiers instead spoke or wrote about being brave or courageous. “Courage,” though, “is not fearlessness,” as some in the nineteenth century thought; “it is being able to do the job even when afraid.”[10] There are many examples that fit this description. Some demonstrate a frightened enlisted Soldier doing his job, i.e., not panicking, listening to orders, using muscle memory, staying alive, and killing the enemy. For example, Berrien McPherson Zettler was a private with the 8th Georgia and later recalled his reaction in his first fight at the First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run). “I felt that I was in the presence of death. My first thought was ‘this is unfair; somebody is to blame for getting us all killed. I didn’t come out here to fight this way: I wish the earth would crack open and let me drop in . . . .’” Once in combat, Zettler “kneeled at a sapling, fired, reloaded, and fired again.” Though he could not see whether he hit a Union Soldier, he remembered “to his right and left the balls” struck “our boys, and I saw many of them fall forward, some groaning in agony, others dropping dead without a word.”[11] This is a realistic, narrative of battle. Fighting through his fear, Zettler did his job and confronted his adversary.

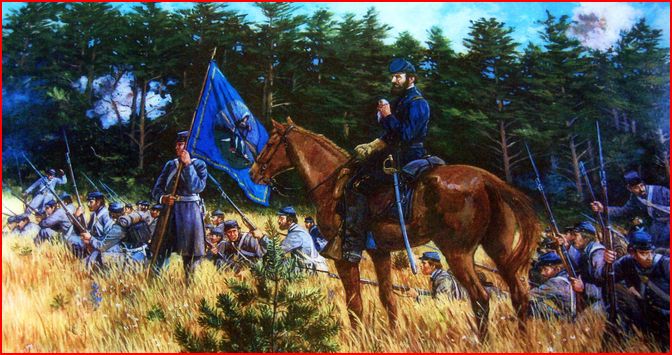

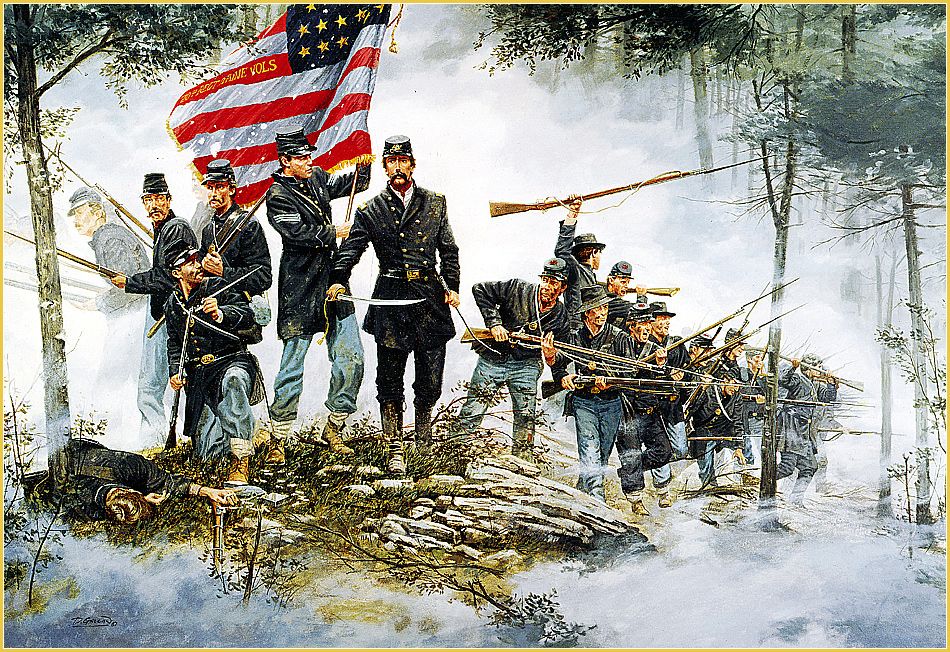

How about the officers? There are plenty of illustrations of commanders pushing their anxiety aside and accomplishing their job, i.e., critically and swiftly thinking in order to keep their men alive, remaining composed, and accomplishing the tactical mission. Everyone remembers the famous scene at First Manassas when Brigadier General Thomas Jackson’s brigade stood their ground. Few probably know he did something just as savvy and gutsy before this incident. As soon as his brigade reached the battlefield, he had the presence of mind to order his men to lie down on the reverse slope of a hill. What’s the big deal? This quick thinking protected his brigade from direct Union artillery fire. Then, at the right time, Jackson motivated his green troops to follow him in a bayonet charge where his brigade captured and held several artillery pieces. Two years later, Colonel Joshua Chamberlain, 20th Maine, led another well-known, daring bayonet charge at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. Does anyone remember the shrewd but unexceptional order he gave prior to the charge? No? Chamberlain directed his left flank to

How about the officers? There are plenty of illustrations of commanders pushing their anxiety aside and accomplishing their job, i.e., critically and swiftly thinking in order to keep their men alive, remaining composed, and accomplishing the tactical mission. Everyone remembers the famous scene at First Manassas when Brigadier General Thomas Jackson’s brigade stood their ground. Few probably know he did something just as savvy and gutsy before this incident. As soon as his brigade reached the battlefield, he had the presence of mind to order his men to lie down on the reverse slope of a hill. What’s the big deal? This quick thinking protected his brigade from direct Union artillery fire. Then, at the right time, Jackson motivated his green troops to follow him in a bayonet charge where his brigade captured and held several artillery pieces. Two years later, Colonel Joshua Chamberlain, 20th Maine, led another well-known, daring bayonet charge at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. Does anyone remember the shrewd but unexceptional order he gave prior to the charge? No? Chamberlain directed his left flank to “refuse the line,” i.e. walk several paces back and bend the left flank so the regiment was in a V shape. This kept his ranks tight so that his out-numbered regiment could withstand several more attacks. How did Chamberlain think of this defensive tactic? He kept his mind calm amid the chaos.

“refuse the line,” i.e. walk several paces back and bend the left flank so the regiment was in a V shape. This kept his ranks tight so that his out-numbered regiment could withstand several more attacks. How did Chamberlain think of this defensive tactic? He kept his mind calm amid the chaos.

Our nation’s history teaches us a lot about responding to fear. Some who panicked faced the perils of turning their backs to the enemy and running the hundred-yard dash with hundreds-to-thousands of their comrades. It took strong leadership to take command and calm the spirits of the men, but it was often done to good effect. Others who allowed fear to get the better of them made themselves scarce in battle. Sometimes these acts of cowardice went unpunished; others times, it was dealt with swiftly and permanently. Out of the millions of Soldiers who served, however, most fought through their fear and did their jobs. Some, of course, had a more difficult time doing this, while staying calm and critically thinking and reacting in battle almost looked easy to others, like Jackson and Chamberlain. How did these officers remain composed? Both had faith in God. It is a good assumption both were familiar with God’s command to the biblical commander, Joshua. “Have I not commanded you? Be strong and courageous. Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged, for the LORD your God will be with you wherever you go.”[12]

Our nation’s history teaches us a lot about responding to fear. Some who panicked faced the perils of turning their backs to the enemy and running the hundred-yard dash with hundreds-to-thousands of their comrades. It took strong leadership to take command and calm the spirits of the men, but it was often done to good effect. Others who allowed fear to get the better of them made themselves scarce in battle. Sometimes these acts of cowardice went unpunished; others times, it was dealt with swiftly and permanently. Out of the millions of Soldiers who served, however, most fought through their fear and did their jobs. Some, of course, had a more difficult time doing this, while staying calm and critically thinking and reacting in battle almost looked easy to others, like Jackson and Chamberlain. How did these officers remain composed? Both had faith in God. It is a good assumption both were familiar with God’s command to the biblical commander, Joshua. “Have I not commanded you? Be strong and courageous. Do not be afraid; do not be discouraged, for the LORD your God will be with you wherever you go.”[12]

[1] https://www.westernjournal.com/exclusive-gen-flynn-forces-evil-want-steal-freedom-dark-night-god-stands-us/. If anyone is wondering, Flynn is from Rhode Island. He grew up in a patriotic, Catholic family who happened to be democrats.

[2] Illustrations: 1. 18th NC Battle flag and 71st New York battle flag; 2. First Battle of Bull Run, chromolithograph by Kurz & Allison; 3. Battle of Stones River as painted by William Travis, c. 1865; 4. Jackson at First Manassas, National Park Service; 5. 20th Maine makes a stand, left flank was pulled back so the regiment was in a V shape, artist Dale Gallon. Painting is available at gallon.com; 6. Bald Eagle and Old Glory.

[3] JoAnna M. McDonald, “We Shall Meet Again:” The First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run), July 18–21, 1861 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001). One professional battalion, the U.S. Regulars, remained calm and covered the retreat. For Nashville, Benson Bobrick, General George H. Thomas & The Most Decisive Battle of the Civil War: The Battle of Nashville (New York: Knopf, 2010), 100.

[4] Larry J. Daniel, The Battle of Stones River: The Forgotten Conflict between the Confederate Army of Tennessee and the Union Army of the Cumberland (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2012), 139. For an overview of the battle see, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/civil_war_series/23/sec6.htm.

[5] Daniel, 139.

[6] Chris Mackowski and Kristopher D. White, A Season of Slaughter: The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, May 8–21, 1864 (California, Savas Beatie, 2013), 79-82.

[7] The act of cowardice was also known as “cannon fever.” For quote and cannon fever, Gerald E. Linderman, Embattled Courage: The Experience of Combat in the American Civil War (New York, Free Press, 1987), 10.

[8] In 1862, one Union Soldier at the siege of Corinth, Mississippi, did this. His comrades were not fooled but did not kill him; instead, the coward was verbally tormented the remainder of his time with the regiment. Bell Irvin Wiley, The Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1952), 87–88.

[9] This was in the 15th Alabama. The private liked to pick fights with his fellow Alabamians in camp but would desert during the confusion of battle, A Walk in Time: “We’re Going in there . . .” A Guide to the Battles for Little Round Top, Valley of Death, Devils Den (Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press, 1999), 13–4. For 9th New Jersey, James McPherson, For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997 ), 51.

[10] Psychologist, John Dollard, studied American combat veterans who fought in the Spanish Civil War. He noted “Courage is not fearlessness; it is being able to do the job even when afraid, Linderman, 19. The nineteenth century perspective of the term, “being courageous” was flowery, and many thought it meant not being afraid in combat. Many memoirs and letters written in the Victorian style of that day describe battles unrealistically. An example would be: “All the men in the regiment valiantly charged and all honorably did their duty as each steadfastly stood under fire.” This is not an accurate depiction of combat.

[11] McDonald, 66 and 69.

[12] Joshua 1:9, New International Version. I am not going to tell anyone how to respond to the current pandemonium. The only things I will say is that turning off my television, reading articles and blogs, researching, critically thinking, discussing with others (my family and combat veteran friends), questioning my local and state politicians, praying a lot, and reading my Bible has calmed my spirits, somewhat. Know this, whatever way you approach a scary situation, you can’t get away from the trauma and fear; you can, however, control the way you deal with it.

“Courage is being afraid but saddling up anyway.” John Wayne

I watched many John Wayne movies with my grandfather. I always felt bad for the horse. The producers couldn’t seem to find a horse big enough for JW.

Thanks for this post. I like that you have used artwork to illustrate your points. I always go for the old CDV, etc. Maybe I will rethink things!

Meg, lots of Civil War artwork online. I had never seen that one of Murfreesboro. Circa 1860s books have some interesting illustrations as well.

A friend once told me that if you can do three things that scare you just about every day, your confidence will just explode. I’d like to think that the soldiers on both sides experienced this too. The mentality of “I survived the fight at Antietam, so I can make it through this too.” Great analysis!

Thank you for this outstanding article