“It is inhuman, to treat our soldiers as such” – An Iowa Newspaper Criticizes the Federal Hospital System

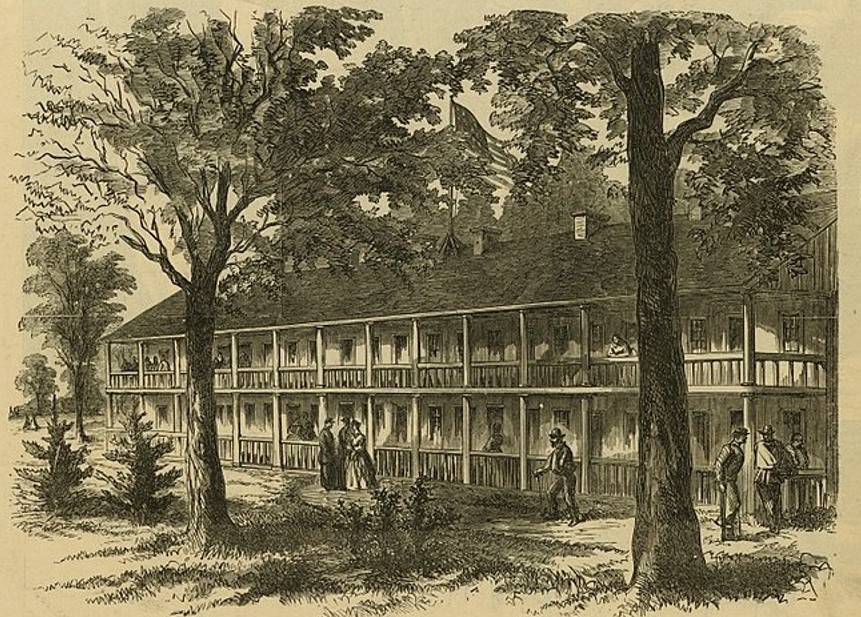

On January 23, 1863, the Cedar Falls Gazette of Cedar Falls, Iowa wrote an article about their visit to the general hospital complex at Jefferson Barracks Military Post. Located just south of St. Louis, the hospital at Jefferson Barracks was one of the busiest hospital facilities in the country, treating over 18,000 soldiers in just four years of war. One member of the newspaper, named “Geo.,” grew ill and was subsequently sent north from Helena, Arkansas to Jefferson Barracks. In the wake of a visit, the members of the Gazette took time to heavily criticize the government’s treatment of wounded and ill soldiers.

Highly critical of the poor sanitary conditions and slow discharge rate for convalescents, the Gazette wrote: “Soldiers are dying every day in the hospitals in St. Louis, who, if they had their descriptive rolls, could be discharged, go home, and get well, instead of being obliged to suffer and die in fetid, loathsome hospitals unable to draw a cent of pay or a rag of clothing, and all because of a non-fulfillment of duty on the part of the officers.”

In addition to this, they wrote about the “barbarous” treatment of incapacitated soldiers, as they were transported to St. Louis from the front. “In being transferred from Helena to Jefferson Barracks [along the Mississippi River], our brother was with three hundred others on a miserable little steamer, and so crowded was the boat that they put the sick on the lower deck, in among the machinery, out on the guards … Many died during the trip, and many more died soon after being landed in consequence of the privations and hardships they were compelled to undergo.” They concluded that “it is barbarous, it is inhuman, to treat our brave soldiers thus.”

While this was in response to their own correspondent’s experience in St. Louis, the Gazette’s article touched on the sanitary, hygienic, and organizational issues that plagued many Civil War hospitals. Though the newspapermen were horrified by what they saw, it should be noted that the vast majority of surgeons, nurses, and volunteers aboard hospital ships and in the general hospitals were doing all they could to both evacuate as many ill and wounded, while also make sure soldiers were convalescing for the appropriate amount of time. To the newspaper, it was not the hospital administration and staff that was at fault, but rather the United States government.

The Gazette article made note that, “As far as our experience goes we have no fault to find with those in charge of the hospitals. At Jefferson Barracks we are sure that all was done that the regulations would admit of … All with whom we came in contact were kind, courteous and attentive, and seemed disposed to do everything in their power to alleviate the sufferings of the sick in their charge. The wards are kept as clean and neat as the parlor of any thrifty house-wife, and especial attention is also paid to the beds, raiment and persons of the sick.” However, the great concern was “the lack of sufficient nurses,” which to them was caused by “the Government which neglects to properly provide for the wants of sick … Justice and humanity imperatively demand a re-modeling of our hospital system.”

Articles such as this brought these concerns to the attention of local leaders, military families, and civilians in order for those conditions and low numbers of nurses to be improved – not just in the Western and Trans-Mississippi theaters, but across the entire front. It makes us wonder as historians how many read this particular article, and how effective these articles were in pressing Washington for hospital reform.

Sources:

“A Trip to Jefferson Barracks,” Cedar Falls Gazette (Cedar Falls, Iowa), January 23, 1863, Newspapers.com.

When the Civil War began, one exuberant Southern politician, L. P. Walker, offered to soak up all the blood spilled with his pocket handkerchief. By the time Memphis fell to Federal forces in June 1862 there was a need for tens of thousands of hospital beds, across the North and South. (In Memphis, alone there were fifteen major Union Hospitals catering for over 10000 patients.) Unfortunately, Hospital care received concern, but not the funding and manpower (woman-power) required. Many of the items required by sick, injured and wounded soldiers were donated; and astonishingly, much of that donated material was stolen from wharves, and then sold to the Government; and much donated fruit and vegetable was shipped to needed sites expeditiously… then sat for days aboard transport, and rotted before it was unloaded.

Lack of care for prisoners of war (think “half-rations”) and inadequate facilities offering minimal treatment provided to hospitalized soldiers are two of the major horrors faced by soldiers of both sides during the War of the Rebellion.

Thanks for broaching this “uncomfortable” topic…

Doesn’t seem any different than the situation today — everyone is looking to the federal government to solve the problem, but the system wasn’t set up to make the federal government an efficient supplier.

Clara Barton and Dorothea Dix addressed the horrors of the way wounded soldiers were treated and worked to clean up the hospitals and provide better care to the men who gave everything.No surprise it took strong women who had to challenge the male status quo but earned the respect of the military leaders by their determination and devotion.

My great great grandfather died at Jefferson Barracks Hospital on July 27, 1865, and was buried the same day in what would not become the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery until nearly ten years after the end of WWII. He was a 38 year old German immigrant who left behind a wife and four children, ages 11, 9, 6 and 2, to become a replacement troop for the 27th Wisconsin after enlisting in Hartford, Wisconsin on October 18, 1864. He reported for duty on Christmas Day when he boarded a boat that took him from Sheboygan to Milwaukee for basic training as a private in Company F along with a half dozen others from Scott Township. They met up with their unit in Little Rock, Arkansas, around the 1st of February and departed a few days later for New Orleans by river boat. They camped for about ten days in Algiers just across the river from the French Quarter, then boarded a transport to cross Lake Pontchartrain to a ferry that took them to Fort Morgan on the far side of the entrance to Mobile Bay. They marched from there to establish a perimeter for most of the month of March to lay siege to Spanish Fort, which fell along with nearby Fort Blakeley after frontal assaults in the first week of April. Many of the forts’ defenders escaped capture by fleeing upriver and the 27th was one of a number that pursued them on foot up the Tombigbee River. After the surrender of General Nathan Bedford Forrest the unit returned to Mobile by boat courtesy of the Confederate Navy. The regiment boarded a ship called the Clinton on the 1st of June and arrived at Brazos Santiago in Texas at the mouth of the Rio Grande on the 7th of June. My great great grandfather was reported ill on arrival, probably yellow fever, and too sick to make the march to Brownsville so evacuated by ship to New Orleans and from there by riverboat to Jefferson Barracks, arriving before the end of June. His cause of death was listed as pneumonia. His tunic was delivered to his widow in Wisconsin, probably by another soldier in his unit who survived hospitalization at Jefferson Barracks. My theory is that two of that soldier’s grandsons married two of my great great grandfather’s granddaughters more than fifty years later.