Burning Bridges to Baltimore

It’s always fun when researching obscure primary sources to come across a good story that has nothing to do with the original search. One such source is the memoir of a Union telegrapher published in 1910 in which he addresses “that vital enterprise which involved the transportation of troops rushing to the defense of the Capital” and includes this story.

It’s always fun when researching obscure primary sources to come across a good story that has nothing to do with the original search. One such source is the memoir of a Union telegrapher published in 1910 in which he addresses “that vital enterprise which involved the transportation of troops rushing to the defense of the Capital” and includes this story.

“Just how this emergency arose on the Baltimore route we will let Mr. William J. Dealy, a valued comrade of the military telegraph, explain:

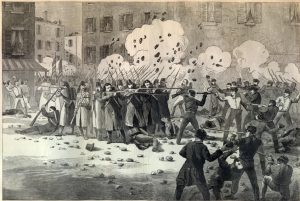

“In April 1861, I was in the service of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad Company, and was sent from my regular station, Magnolia, to a new office at Back River, six miles north of Baltimore. There was a guard of six or eight armed men in the service of the railroad company sent to Back River, to prevent interference with, or damage to, the bridge. April 19th, the Sixth Massachusetts Regiment, on its way to Washington, unarmed and with-out uniforms, was attacked in the streets of Baltimore by a mob and driven back. These retreating soldiers caused extra vigilance on the part of the guard and myself.

“I was on duty fifty-six hours, and finally, becoming exhausted, went to bed about 2 a.m., April 22nd, only to be awakened and captured three hours later. The night mail train from Philadelphia to Baltimore passed south safely and reached Canton, a suburb of Baltimore, where it was stopped by a force of eighty policemen and eighty militia. A bridge crossing a small creek or canal at Canton had been destroyed to prevent this train from going farther. After the passengers and baggage were landed, the policemen and militia took possession of the cars, and compelled the engineer by threats to start northward.

“I never fully understood why the police and militia did the very thing that it was our duty to prevent and became bridge burners, but I remember their explanation was that Baltimore was excited, and it was necessary, as a means of cooling the excitement, to prevent troops from passing through the city for the present. The only effectual way to prevent it was to cut off communication by burning the bridges. They claimed to have the authority or sanction of the city officials for their action.

“The officer in command of these one hundred and sixty men was a Major Trimble, who had previously been superintendent of the railroad, and was subsequently a major-general in the rebel army. The first stop of the train on its way back was at Back River, about 5 a.m., where I was hurriedly awakened, and told to jump aboard. I took my instruments with me, considering myself lucky in being saved from the bridge burners that had been long expected, as I supposed the police and militia had come to protect the road. They then cut down several telegraph poles, cut the wire, and started the train.

“The captain of the militia, whose name, I believe, was Matthews, told me I was the first political prisoner of the war. Our next stop was Gunpowder bridge, nineteen miles north of Baltimore, where we stopped but a few moments. We arrived at Magnolia, two miles farther north, just as the operator, J. A. Swift, now electrician in the Storm Signal Bureau, Washington, was coming down the road from his home to begin the labors of the day, and he was also made a prisoner.

“Our next stop was on the bridge that crosses Bush River. Bush River is about six miles north of Magnolia, or twenty-seven from Baltimore. The bridge is three-quarters of a mile long, and built of trestle work, the same as Gun-powder bridge, which is about a mile long. We were met on the bridge by a south-bound freight train in charge of Conductor Goodwin. It then transpired that the object of the party was to go to Havre de Grace (thirty-six miles from Baltimore), get possession of the railroad company’s steamer Maryland, used to transport trains across the Susquehanna, and scuttle her. In this, however, they were defeated.

“Swift and myself were now anxious to leave the train, as we wanted to get to the next telegraph office, Perrymansville, a mile and a half distant, and warn Havre de Grace, but the doors of the car were locked, and a sentinel paced each platform. Conductor Goodwin, however, evidently changed their plans, by telling them it was known at Havre de Grace that they were on the road, and that troops were there to receive them. In fact, he intimated that they might, since he left, have received orders to march and meet them.

“The freight train, after considerable switching, the road being single-track, was then allowed to pass south. The road has since become double-track, and the old steamer Maryland has been superseded by a magnificent bridge across the Susquehanna. The Maryland is now owned by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad Company, and transfers trains, passengers and freight between the Pennsylvania depot at Jersey City and the New Haven depot at Mott Haven. It is a fine ferryboat, and when on the Susquehanna River, had three tracks and could take seven cars on each, twenty-one in all. She has since been remodeled and can be seen any day on the East River with her trains.

“The draw of the Bush River bridge was then burned and we returned to Gunpowder bridge, the draw of which was also burned. At the southern end of this bridge is Harewood station, where we breakfasted. Swift had been released at Magnolia on the way back. About noon we started again on our backward way, and I found myself again at Back River.

“The bridge here was about 800 feet long and the bridge tender, a Mr. Butler, since dead, who had been a sea captain, and used to salt his vessel to make it fire-proof, had also salted the bridge. His plan and practice was to place salt, rock-salt generally, along the timbers in the evening. The dew of night would dissolve it, and the timbers would become impregnated with the salt. When sparks from passing locomotives fell upon the bridge, the salt would ooze out in moisture and smother the fire. Several unsuccessful attempts were made to burn this bridge, but the salt saved it.

“I expected to be released here, but it was suggested that I join a light artillery company, then in Baltimore, about to start for Richmond, and probably with the hope of securing me, they took me to Baltimore. I was then released, walked back to my station, Back River, six miles, and after resting, walked to Havre de Grace, thirty more miles. Crossing the burned bridges on hands and knees, and the Susquehanna in a row boat, I took train to Philadelphia, and after reporting to A. W. Decoster, superintendent of telegraph, was taken to S. M. Felton, president, and to Mr. N. P. Trist, paymaster.”[1]

The memoir’s author, John Emmet O’Brien, described telegraphy as “the highest development of electrical science in the middle of the century” and Mr. Dealy as “the ideal telegrapher, and a prince of all cheerful, good fellows.” They were unobtrusive, usually behind the frontlines but not always out of range, and critical players in momentous events. This was just the beginning of their adventures. By 1910, William J. Dealy would be manager of the Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Company of New York.

[1] John Emmet O’Brien, Telegraphing in Battle: Reminiscences of the Civil War (Wilkes-Barre, Pa, 1910), 5-8, 164.

The period immediately after eruption of war at Fort Sumter until a significant loyalist garrison was established at the U.S. Capital end of April was marked by confusion, rumor-inspired anxiety and competing claims IRT State’s rights and Federal Government rights, and which took precedent. The State of Maryland, border State and Slave State, attempted to navigate a middle path of neutrality, similar to the course taken by border States Kentucky and Missouri, without acknowledging the significant difference: Maryland bounded the Federal Capital; and her actions and permissions (denial of permissions) directly impacted on the Federal Government, and the ability of that government to conduct its business.

Following the disruption of troops answering the call of Federal service (the 6th Massachusetts was not sworn into Federal service until 22 APR 1861) the Governor of Maryland, Thomas Hicks, responded to urgent demands of City Officials at Baltimore to “close Baltimore to passage of any more Northern soldiers” by… Here it gets murky: Baltimore officials claimed Governor Hicks authorized destruction of railroad bridges north of Baltimore; Hicks afterwards denied he gave his consent to this action. The Police Commissioner of Baltimore, who ordered the destruction, claimed he received approval of the Governor.

Thanks to Dwight Hughes for revealing another aspect of this confused, and confusing period of the Civil War.

Mike: Thanks for your excellent context.

James A. Swift, the other boy captured by the Baltimore rebels, was one of my great, great granddads. He joined the War Dept’s Telegraph staff in 1862 at age 15 and worked for Thomas Eckert until the end of the war and went on to become one of the country’s most skilled telegraph operators and head of the Army’s Signal Corps school in the 1880s.