Incendiaries on the B&O: The Burning of the Fish Creek Spans During the Jones-Imboden Raid (Part I)

Civil War cavalry raids often rank among the most romantic of Civil War tales. This often has to do with the characters most often associated, with names like Stuart, Morgan, Mosby, Rosser, Gilmor and others. These raids would be recalled in song and verse and were often recorded by civilians in places like Missouri, Ohio, West Virginia, and Indiana as the time when the war literally came to their doorstep.

Another hallmark of cavalry raids were local civilians and home guard troops working either in concert with or to impede the progress of the raiding party. Raids were by their nature quick-moving operations, with the pursuers often running to either catch up or close off an avenue of escape. Civilians and home guard troops would sometimes find themselves as the only or the last line of defense to protect a city, railroad, or river crossing, or conversely, as party to the destruction of bridges, railroads, or materials of war. These actions could have reverberations beyond their immediate neighborhood. Having grown up along the path of Morgan’s Raid in eastern Ohio, where home guard units successfully hemmed in Morgan’s command from several Ohio River crossings, these types of stories have always captured my attention. We’ll look at one such story today.

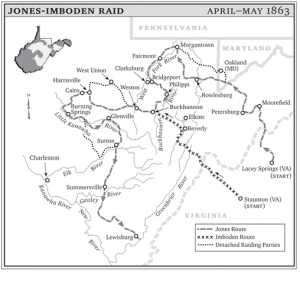

The Jones-Imboden Raid ranks among my favorites in Civil War historiography. Lasting from April 20 – May 25, 1863 and covering some 1,100 miles between the two columns, the raid has not received the attention or notoriety of its peers. Its commanders, William E. “Grumble” Jones and John D. Imboden, don’t exude the romantic notions of the likes of Stuart, Mosby, or Morgan. And to be sure, the raid occurred at a time when there was a lot going on, including the battles of Chancellorsville, VA, and Jackson, MS; the Vicksburg Campaign; the sacking of Lawrence, KS; and more.

The brainchild of Imboden and Captain John Hanson McNeill, the raid was envisioned as a means of crippling the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad in Maryland and western (soon to be West) Virginia by destroying bridges, viaducts, and tunnels along Abraham Lincoln’s vital lifeline to the west. Imboden and Jones would also plan to scatter several small Federal garrisons, gather needed horses and cattle, enlist new recruits that were disaffected with the West Virginia statehood movement, and threaten the burgeoning government forming at Wheeling and its coming elections. The raid would combine efforts from multiple Confederate departments and nearly 5,000 troops of several commands.

The reach of the Jones-Imboden Raid was just incredible, with Jones taking a northerly route and Imboden southerly. Jones would reach as far northwest as Morgantown, (West) Virginia – even sending riders into the southwestern corner of Pennsylvania to gather horses – before turning south to Fairmont. After a brisk fight at Fairmont the raid achieved one of its most significant feats in the destruction of the B&O bridge across the Monongahela River on April 29, 1863, the longest and most expensive iron span on the B&O main line. The raid would continue for another three weeks and reach even farther southwest to Burning Springs, near Parkersburg on the Ohio River, where Jones destroyed an oil works and some 12 – 15,000 barrels of oil.

All told the raid resulted in the damage or destruction of an astounding 26 B&O bridges, dozens of miles of track damaged, two engines and at least twenty cars destroyed, company buildings and water stations ransacked, and many miles of compromised telegraph lines. According to the B&O’s annual report for 1863, expenses for the year ballooned more than $500,000 from 1862 and nearly $700,000 from 1861, due in large part to the damage inflicted from the raid.[1]

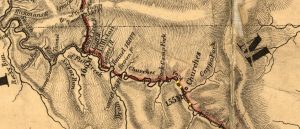

While reviewing the B&O annual reports – which are wonderful reading, by the way – I was surprised to find noted that three bridges had been burned on the main line at Church’s Fork and Cappo Fork, a full 30 miles west of Fairmont, where Jones defeated some 500 Federal troops and home guards before continuing south. Perhaps riders moving west on the B&O in search of horses had burned the bridges behind them, I thought. However, if that were the case, they would surely have passed several far more important bridges at Mannington and Farmington. Why spare those in favor of these smaller, seemingly out-of-the-way spans farther out the line?

While neglected in favor of the more contested stretches of the Baltimore & Ohio, the main line past Fairmont was actually a critical stretch of the line between the Monongahela and Ohio rivers. Confederate troops understood this earlier in the war when they burned two B&O bridges over Buffalo Creek at Mannington in May 1861, precipitating George B. McClellan’s invasion of western Virginia. The landmark study The New World in 1859 notes that after passing Glover’s Gap and its 350 foot long tunnel, “the line descends by Church’s Fork of Fish Creek…passing the ‘Burton’ station, the route continues down a stream to the crossing of a tributary called “Cappo Fork,” 4 miles from Glovers Gap. The road now becomes winding, and in the next 4 miles you cross the creek 8 times.”[2] One Federal soldier traveling through this stretch of the B&O just a few months after the raid termed it “the worst, crooked railroad and roughest country that you can imagine. In fact, it is nothing but one continuous hollow…”[3]

With so many water crossings and tunnels in so short a distance, this stretch of the line served as a bottleneck for moving troops and material. As a result of the raid’s apparent reach to this section of the B&O, two Federal commanders more accustomed to commanding armies in the field would instead be called on to secure these critical spans in a backwaters area of the war. The effects of their burning would continue to smolder after their repair…

[1] B&O Annual Report, 1863. Available via the Hathi Trust.

[2] Bailliere, H. The New World in 1859. H. Bailliere: London. 1859. pg 16.

[3] Frank Wallace, Co. H 3rd PA Militia, July 18, 1863. Rich Condon Collection.

Great stuff!

Thanks, Ed!

Jon-Erik, when you cover the rest of the story, I hope you will direct us to some of the sulfuric outbursts from B&O officials at the destruction of their precious infrastructure. Their smoking comments are always entertaining and enlightening. The North needed that rail line. Not incidentally, how quickly were those bridges repaired?

Hi Rosemary,

Temporary trestling so as to make the bridges passable to traffic was in place by May 4, with permanent repairs completed later in the summer. By 1863 the B&O had become quite efficient at making repairs along the line!

Excellent post! Wasn’t all boots, plumes and sabres, was also crowbars and torches?

Thanks, John. The Jones-Imboden Raid was definitely more utilitarian than mystique!

I had read in OR that Imboden claimed his cavalry burned the RR bridges around Burton. Imboden had sent the 18th Va. cavalry north to meet up with Jones. I believe he said his cavalry burned the bridges northwest of Fairmont. Have you ever heard this?