Behind Enemy Lines in Kentucky

ECW welcomes back guest author Stuart W. Sanders….

Garry Adelman and Kristopher White from the American Battlefield Trust recently filmed content at multiple Civil War sites in Kentucky for the Trust’s Facebook page.

As the former executive director of the Perryville Battlefield Preservation Association who has written books about the battles of Mill Springs and Perryville, I was honored to help them film at those two sites. At those battlefields I shared two similar stories about Confederate generals who wandered behind enemy lines. Although the outcomes were different for the two officers, the episodes got me thinking about how poor visibility and mistaken charges of friendly fire affected both battles

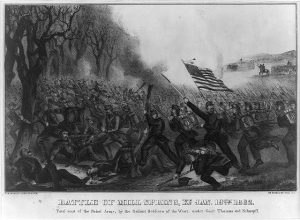

When Mill Springs was fought in south-central Kentucky on January 19, 1862, bad weather hindered the Confederate attack. A driving rain and deep mud slowed the rebel advance and led to piecemeal attacks against the Union line. Because many of the Southern units carried flintlocks, many of their muskets (possibly one-third) failed to fire in the rain.

Thanks to a persistent fog, visibility was also terrible. One Union soldier wrote: “We could not see the enemy in person at first, but fired at the gun-flashes.”

This poor visibility had deadly consequences.

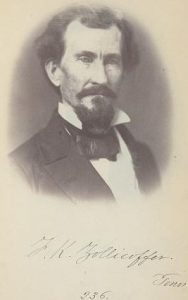

At the height of the action, Confederate Brig. Gen. Felix Zollicoffer, one of the rebel brigade commanders, discovered that a gap existed between several of his regiments. Therefore, Zollicoffer rode into the gap to find his missing troops. With mist and black powder smoke hanging across the battlefield, Zollicoffer moved toward what he thought was a friendly regiment that was firing at his soldiers.

When Zollicoffer neared the mystery unit, he encountered another mounted officer. It was Union Col. Speed Fry, who led the 4th Kentucky Infantry Regiment. Because Zollicoffer was wearing a blue cap, blue trousers, and a white gum overcoat that covered much of his uniform, Fry thought that Zollicoffer was a fellow Union officer.

“His near approach to my regiment, his calm manner, my close proximity to him, indeed everything I saw led me to believe he was a Federal officer belonging to some of the regiments just arriving,” Fry reported.

Zollicoffer pointed to the mystery regiment, which was Fry’s 4th Kentucky. “We must not shoot our own men,” Zollicoffer told Fry. “Of course not,” Fry responded. “I would not shoot our own men intentionally.” Shortly thereafter, another Confederate officer appeared from behind a tree and fired at Fry. Because Zollicoffer had approached from that direction, Fry realized that Zollicoffer was a Southern officer. Fry drew his revolver and fired. At the same time, members of the 4th Kentucky Infantry let loose a volley. Zollicoffer fell dead, struck by three bullets.

Eventually, Brig. Gen. George H. Thomas, the Union commander at Mill Springs, ordered his troops to charge the weary Confederates. The Federal advance sent the rebel army reeling, and the battle proved to be an important early Federal victory that helped keep Kentucky in Union hands at an important stage of the Civil War.

Nine months later, on October 8, 1862, another Confederate general accidentally wandered into Union lines at Perryville while investigating charges of friendly fire. As I explain in an article that I wrote for the American Battlefield Trust, this incident also led to the destruction of one Union regiment.

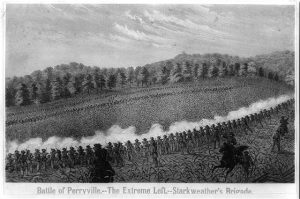

After the Battle of Perryville had raged for about four hours, both flanks of the Union Army of the Ohio’s I Corps were pushed back to a road intersection called the Dixville Crossroads. As the sun began to set, Union Col. Michael Gooding’s brigade, part of the Union III Corps, was sent to reinforce the area around the crossroads.

When Gooding reached the intersection, he reported, “I found the forces badly cut up and retreating (they then having fallen back nearly 1 mile) and were being hotly pressed by the enemy.” He deployed his 1,400 men near the intersection. The 22nd Indiana Infantry, led by Col. Squire Keith, took up a position on the far right of Gooding’s line. They immediately engaged the enemy, pressed forward, and soon found themselves fighting along the Mackville Road, about 100 yards east of the intersection.

As darkness fell, Confederate Brig. Gen. St. John R. Liddell sent his Arkansas troops to support Brig. Gen. S.A.M. Wood’s brigade. Liddell’s soldiers neared the Mackville road and fired on “a dark line” located less than thirty yards away. Immediately, the rebels heard cries of “You are firing upon friends; for God’s sake stop!”

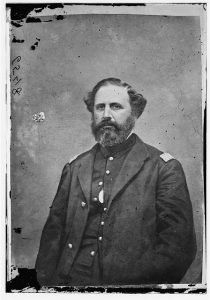

The musketry sputtered to a halt. Immediately, Confederate Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk, the second-in-command at Perryville, appeared and asked Liddell why his troops had stopped firing. When Liddell told Polk that his men had shot friendly troops, Polk responded, “What a pity. I hope not . . . Let me go and see.”

Polk rode to the road and found the colonel who commanded the “dark line” of men that had endured Liddell’s musketry. A furious Polk asked the officer why he was firing upon “his friends.” The colonel replied, “I don’t think there can be any mistake about it. I am sure they are the enemy.” Polk, insisting that they were friendly troops, asked the officer for his name. He was Col. Squire Keith of the 22nd Indiana Infantry.

Unsure of Polk’s authority, Keith asked the Confederate officer to identify himself. Polk later wrote that he decided to “brazen it out.” He rode up to Keith and said, “I’ll soon show you who I am. Cease firing at once.” Polk then rode down the Union line, shouting for the Hoosiers to stop shooting.

When Polk reached the end of their line, he rode back to Liddell. “General, every mother’s son of them are Yankees,” Polk cried. Liddell’s men then unleashed a volley. Polk later said that hundreds of muskets “blazed as one gun . . . the slaughter of that Indiana regiment was the greatest I had ever seen in the war.”

Liddell’s men annihilated the 22nd Indiana and Gooding’s entire brigade quickly withdrew past the Dixville Crossroads. Liddell later said that “The Federal force had disappeared everywhere. The ground before my line was literally covered with the dead and dying.”

The 22nd Indiana, which numbered 300 men, suffered a staggering 65.3 percent casualties, the largest loss of any regiment at the Battle of Perryville. Among the dead was Colonel Keith.

What were the consequences of these two episodes of mistaken friendly fire that led Zollicoffer and Polk to wander into enemy lines?

First, it is telling that neither general sent an aide to investigate the supposed friendly fire. Both officers rode forward alone to identify the mystery regiments. This led to Zollicoffer’s death and, had Polk been unable to dupe the Hoosier troops, could have led to his demise or capture.

While Zollicoffer’s death at Mill Springs likely did not affect the outcome of the battle (the poor visibility and battlefield confusion meant that few rebel soldiers knew that Zollicoffer had been killed), his loss hurt Confederate morale, especially in his home state of Tennessee. Conversely, Zollicoffer’s death, widely promoted in northern newspapers, bolstered Union morale.

Colonel Speed Fry, who was given credit for killing Zollicoffer, became a national hero and was eventually promoted to brigadier general. The shooting of the Confederate general, however, was the zenith of his military career.

At Perryville, Polk survived his accidental reconnaissance. This led to the destruction of the 22nd Indiana and brought the battle to a close. Polk, his nerves lost after riding behind the Hoosier regiment, immediately halted the Confederate assault in that sector of the battlefield, even though multiple brigade commanders wanted to press the attack. Had the rebels seized the Dixville Crossroads, they could have cut off the Union I Corps and delivered a staggering blow.

One wonders if Polk thought of Zollicoffer when he rode down the Union line, telling the 22nd Indiana to cease fire. Although Polk was fortunate at Perryville, his luck did not hold. In June 1864, he was killed by a direct hit from a Union artillery shell near Marietta, Georgia.

Stuart W. Sanders, the former executive director of the Perryville Battlefield Preservation Association, has written books about Mill Springs and Perryville. His latest book, “Murder on the Ohio Belle,” examines Southern honor culture, violence, and vigilantism through the lens of an 1856 murder on a steamboat.

What fascinating stories, especially about General Polk. Why didn’t Fry take Zollicoffer prisoner? The lack of visibility in reenactor videos gives some indication of what it was like when the firing began. It’s hard to know how officers could assess the situation.

Thanks, Katy! Glad you enjoyed it!

When Fry was speaking with Zollicoffer, another Confederate soldier appeared and fired at Fry. Therefore, I think that Fry reacted quickly because he feared that his life was in danger. Zollicoffer was struck with one pistol shot (Fry’s) and two Minie balls, so multiple Union soldiers fired at the same time. The press, however, gave Fry credit for the killing.

After the fight, Zollicoffer’s body became a curiosity on the battlefield. Union soldiers took pieces of the general’s clothing, buttons, and locks of his hair as souvenirs. Some soldiers dipped sticks in Zollicoffer’s blood and kept those. His body was embalmed and then sent to Nashville, Tennessee, where he was buried.

General Kearny at Chantilly rode over to Rebel lines on a muddy dark field of battle and they put a bullet in him. He had been warned that there were rebels across the way, even shown a captured reb, but disregarded evidence to scout the area because he wanted his division to charge upon the enemy and a Confederate presence at that location would have been on the flank of his attack. With his death and looming gloom of rain clouded twilight, the charge did not transpire and overnight from the field did the Union troops retire.