First Battle of Ironclads: Myths, Facts, What Ifs

Today is the 159th anniversary of the battle and my new Emerging Civil War Series book, Unlike Anything That Ever Floated: The Monitor and Virginia and the Battle Hampton Roads, March 8-9, 1862 is just hitting the shelves. Time for a few interesting myths, facts, and what ifs.

Today is the 159th anniversary of the battle and my new Emerging Civil War Series book, Unlike Anything That Ever Floated: The Monitor and Virginia and the Battle Hampton Roads, March 8-9, 1862 is just hitting the shelves. Time for a few interesting myths, facts, and what ifs.

- The infamous Rebel ironclad was the Merrimac.

False. She was officially commissioned the CSS Virginia when completed. However, most Northerners and many Southerners—including her own officers—referred to her as Merrimack or Merrimac after the former steam frigate USS Merrimack upon whose hull the ironclad was constructed.

Merrimack was named for the river that originates in New Hampshire and flows through the Massachusetts town of Merrimac (without the final “k”). The spellings are still widely confused. The misspelled Monitor-Merrimac bridge-tunnel crosses Hampton Roads today. The engagement is still incorrectly referenced—with memorable alliteration—as the Battle of the Monitor and the Merrimack or Merrimac.

- John Ericsson invented the rotating, armored turret.

False. Monitor’s inventor claimed only to have been the first to successfully construct and deploy the device. The idea had been circulating among engineers for decades. An American engineer had a patent for which Ericsson paid royalties. A British competitor was testing a superior design that would supersede Ericsson’s in subsequent developments.

- Monitor and Virginia were the first ironclads.

False. Great Britain and France were in an ironclad arms race. The first such warship was the French Gloire (1859) followed by the British HMS Warrior (1860), an all-iron vessel representing the epitome of contemporary naval engineering. During the Crimean War in 1855, British and French ironclad floating batteries, mortar vessels, and gunboats reduced Russian forts to rubble while deflecting savage fire from heavy shore guns.

- Monitors were powerful warships.

Partially true. Fifty monitors would be built during the war in a bewildering range of one, two, and three-turret classes. But as a warship type, they were not up to the hype and proved to be of limited utility. With low profiles, monitors were not seagoing vessels and with few weapons, they were not effective against shore fortifications, although they did neutralize several Confederate ironclads.

- What if Monitor had used full charges?

Concerned about bursting a gun in the confined and untested turret, the Navy Department ordered Captain Worden to use half charges (15 lbs. powder) in his two XI-inch Dahlgren smoothbores. Worden concluded that full charges—which afterwards were safely used—would have penetrated Virginia’s armor.

- Who was Virginia’s commanding officer?

No one. She did not have an official commanding officer. Confederate Navy Secretary Mallory wanted his most aggressive officer, Captain Franklin Buchannan, for this prestigious position but a more senior officer also coveted it. So, Mallory appointed Buchannan to a new position commanding all naval units in Hampton Roads with the title of flag officer. He flew his flag and directed the battle from Virginia as his flagship.

- How much armor?

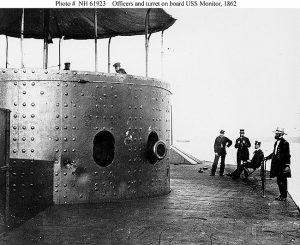

Monitor had eight layers of 1” iron plates on the turret, five layers of 1” plates over oak and pine backing in the armor deck belt, and two layers of ½” iron over oak and pine planks on the deck. Virginia had two layers of 2” plates over 2’ of oak and pine backing on the casemate.

- How many casualties?

Virginia’s after pivot gun delivered a 68-pound explosive shell against Monitor’s pilothouse from about 20 yards. Peering through the narrow viewing slit, Captain Worden was stunned and temporarily blinded. He recovered his right eye, but the left was destroyed and his face permanently blackened. Worden had a long career retiring as an admiral.

One of Monitor’s gunners incautiously leaned against the turret bulkhead just as a Rebel shot whanged against the outside flinging him clean over the guns to the deck, knocking him senseless, and injuring his knee. Another seaman’s head was only inches from the point of impact. “I dropped like a dead man,” he recalled. Both recovered fully the following morning, the only battle casualties among the crew.

Virginia had 2 killed and 19 wounded the day before while destroying the USS Cumberland and USS Congress but only a few injuries against Monitor.

- What if Virginia had more solid shot?

Confederates had not anticipated Monitor’s appearance that morning; they loaded Virginia mostly with explosive shells for use against wooden hulls. Their few rounds of solid shot were quickly expended. Shells tended to explode on the surface of iron armor, dissipating their energy externally rather than penetrating while solid shot had better smashing power. Confederates maintained that more solid shot would have penetrated Monitor’s armor.

- Iron was clearly superior to wood hulls.

Not necessarily. Metallurgy was advancing, but iron still suffered inconsistencies in ingredients and manufacture. Bad batches could be as brittle and dangerous as wood splinters in combat, one of the reasons senior naval officers were cautious. Wooden hulls also were generally lighter, more stable and flexible in heavy seas, therefore faster, and did not require such frequent industrial maintenance.

- Union ironclads were built solely to confront Rebels.

False. The Union ironclad building program was conceived in 1861 primarily to confront the rapidly expanding European threat. The British seriously considered intervention with force if necessary to prevent serious damage to their economy and domestic stability from cotton shortages and trade disruptions. The possibility of a third war with the world’s most powerful nation, now armed with seagoing ironclads, was real and immediate.

The first two Union vessels approved would become the USS New Ironsides and USS Galena, both standard steam frigates with iron armor. Monitor was considered a dubious experiment, authorized only because she might be ready in time to counter Virginia.

- Who was the most frightened man?

According to Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, the most frightened man was Army Secretary Edwin Stanton who could not fathom a two-gun, iron raft stopping at 10-gun iron frigate. President Lincoln called an emergency cabinet meeting in his White House office that morning.

Stanton moaned (wrote Welles) that the Rebel monster would destroy the entire Union fleet, halt the Peninsula Campaign, come up the river, destroy the Capitol, then take out Boston and New York. Welles caustically described Stanton peering anxiously out the window down the Potomac expecting a cannonball to land in the room any minute. Virginia could not safely leave Hampton Roads, but they did not know that.

- Why was Virginia armed with an iron ramming beak?

The ram, that fearsome weapon of ancient Mediterranean rowing galleys, had not been seen since the Battle of Lepanto (1571) when a Christian coalition defeated the Ottoman fleet. Never practical for sailing warships, the ram was revived by steam and propeller propulsion.

On March 8, Virginia knocked a hole in the USS Cumberland “big enough to drive a horse and cart through” and down she went. Warships of many nations sported ramming beaks into the early twentieth century—see the Spanish-American War veteran USS Olympia for example—but they were rendered obsolete by increasingly powerful and longer-range guns.

- Did Virginia slow the Peninsula Campaign?

Probably. General George McClellan, who didn’t need much deterrence, planned on waterborne transport and supply along with naval artillery support on his left flank, which he didn’t get. Virginia threatened Hampton Roads through March and April until Union troops recaptured Norfolk and the navy yard, forcing Confederates to destroy her. Monitor also patrolled the waters but was ordered not to reengage Virginia for fear of serious damage putting the little ironclad out of commission.

- Ironclads were invulnerable.

Not really. Both Monitor and Virginia were thought to be weak at the deck edge junction of armor and hull. When a Rebel shell slammed Monitor’s deck edge, Captain Worden crawled out the turret gun port, walked across the deck and lay down on his chest with musket rounds pinging all around to examine the damage, which was not bad, so he crawled back in.

Not really. Both Monitor and Virginia were thought to be weak at the deck edge junction of armor and hull. When a Rebel shell slammed Monitor’s deck edge, Captain Worden crawled out the turret gun port, walked across the deck and lay down on his chest with musket rounds pinging all around to examine the damage, which was not bad, so he crawled back in.

Worden also was worried about the turret, fearing that a hard hit just in line with the vertical axis would distort the central supporting shaft and stop rotation, but the mechanism took all shocks. A 150-pound projectile hitting straight on from 30 yards did not crack or split the iron; it created a smooth dent, “a perfect mold” of the shell, 2.5 inches deep, which bulged right through 8 inches of armor.

Due to a design error, Virginia sat too high in the water, exposing a strip of unarmored hull below the casemate edge. Confederates fretted that Monitor would strike there and probably sink her, but they didn’t. Union rounds blew holes in the top iron layer, cracked the lower, and bulged the wood backing in spots, along with obliterating railings, boats, stanchions, flagstaff, gear topside, and perforating the smokestack.

However, they concluded, if Monitor had used full instead of half charges, or if she had planted two or three shots in the same spot, Virginia’s armor probably would have been breached.

Lots more to learn, so check out the book. If you don’t know the story, this is the place to begin; if you think you know the story, you will be surprised.

Highly recommend William Roberts’ “Civil War Ironclads” about the Union ships, but as an old Engineering Duty officer with a background in both shipbuilding and repair I probably have more interest in the programatics than the typical Civil War student.

Scott: Yes, great book and a prime source for my Hampton Roads book. Technology and engineering are, after all, central themes in the story and must be illuminated for readers. Thanks.

Commendable effort to “stop the rot.” The fact schoolkids are still taught “Monitor vs. Merrimac” in History classes illustrates the depth of the problem: too much simplification; over-reduction of facts to an end result… of fiction; ongoing confusion HOW to incorporate Naval activities into what is popularly regarded as a Land war. Focus on USS Monitor vs. CSS Virginia allows disregard of: timberclads; inland river ironclads; neutralization of ironclads by wooden-hulled ships at forts below New Orleans in April 1862 (so much for “ironclads made wooden navies obsolete.”) Other Civil War operations that are mostly ignored: early use of torpedoes; commerce raiders beyond CSS Alabama; barrier chains used to block navigable streams; introduction of 13-inch mortars on rafts and sloops; submarines (more than just the Hunley); use of at least one aircraft carrier…

Too many facts make your head explode.

[Also want to remark that “HMS Warrior still floats at Portsmouth in UK as museum ship.”]

Right on, Mike. See my first book, “A Confederate Biography: The Cruise of the CSS Shenandoah,” for commerce raiders other than Alabama. I’m working on a new book covering the river campaigns, which will address other points you make, particularly the critical role of combined army-navy operations. Thanks.

I know this has no relevance to this article, but for what it’s worth, I still think the USS Monitor is just flat-out a cool looking vessel. As for the CSS Virginia, its design bears a strong resemblance to some of those being produced today to enhance stealth features of those vessels. Though stealth wasn’t a goal (at least not one that I am aware of) where the “Virginia” was concerned, I can’t help but see some ‘lineage’ between the “Virginia” and more modern vessels like the USN’s experimental research ship the “Sea Shadow”, which saw service from the mid-80s until retired in 2006. .

Thanks for the comment. I agree. The two ships resemble each other in outline although Sea Shadow’s was intended to reduce radar profile while Virginia was just an iron shed on a ship’s hull, and she was hardly stealthy. One observer likened the Rebel ironclad to a “huge terrapin with a large round chimney about the middle of its back.”

Excellent post, concisely bringing together a number of relevant comparisons between the ships. The Monitors may have been “One and done” designs, but they worked for that One at Hampton Roads.