On The Eve of War: Yorktown, Virginia

Yorktown, Virginia, the scene of the culminating engagement of the Revolutionary War, was a quiet village perched on the sandy bluffs above the York River when war came again to the Virginia Peninsula. With the capital’s transfer from nearby Williamsburg to Richmond in 1780, Yorktown’s population began to decline. Adding to the decline was the unforgiving impact of tobacco agriculture which drained soil of its nutrients, and the subsequent movement of families west to newer lands in Virginia and beyond, like Kentucky and Tennessee.

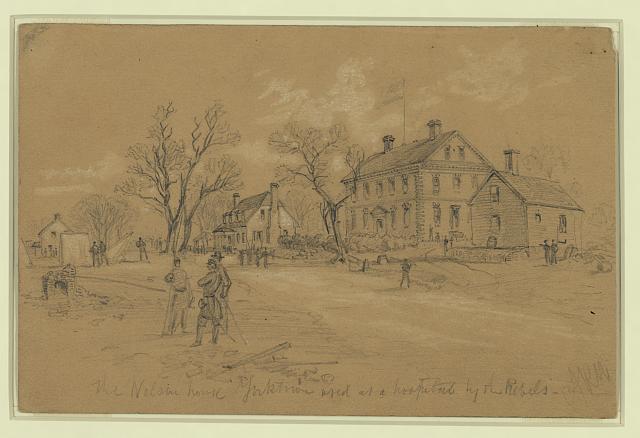

The York County courthouse stood in the center of town, and nearby was Grace Episcopal Church, dating to 1697. In the churchyard was the grave of Thomas Nelson, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Nelson’s large brick home stood a few blocks away. Also prominent on Main Street was the Customs House, a reminder of the town’s important shipping heritage. Along the waterfront in the one of the rocky outcroppings was a local landmark called Cornwallis’s Cave, where legend said that the British general sought shelter during the 1781 siege (he probably didn’t).

The town’s economy was tied to the river and shipping as it possessed a good port that could accommodate large vessels. Three parallel streets, Water, Main and Ballard, ran east to west in line with the river, crossed by eight other streets. About 200 resided here in 1860.

Encircling the town were remnants of the 1781 British earthworks, largely eroded but still discernable. Just south of the village in 1859, Virginia militia dedicated a monument at the site where British officers offered Cornwallis’s sword to Washington and Rochambeau.

In fact Congress had voted to place monument to the American victory upon receiving the news in 1781, but budget concerns and political wrangling prevented it from happening. Up until 1859 nothing commemorated the victory that sealed American independence. Still, memories of the Revolution loomed large, and soldiers from both sides noted with interest that their armies converged on this historic setting.

A soldier in the 1st Massachusetts Infantry wrote on seeing the town in 1862 that it was in a “state of dilapidation and decay. Notwithstanding its historical important, there did not seem to be enterprise enough among its inhabitants to keep it in a neat and respectable condition.”

When the armies approached in the spring of 1862, both saw Yorktown in light of its Revolutionary history, and found inspiration from engaging on the site of the previous decisive siege. The 1859 surrender monument did not survive the siege of 1862, as soldiers chipped away at it for souvenirs.

Although nearby Williamsburg is better known for its colonial restoration, much of downtown Yorktown was restored as well. Several buildings from the late 1600s and early to mid-1700s line Ballard and Main Streets. Yorktown is not nearly as crowded as Williamsburg and offers a quiet place to stroll and take in colonial history.

The fact that a Revolutionary War historic site in the South was marked with a commemorative plaque just prior to eruption of the War of the Rebellion illustrates one of the paradoxes of that conflict: BOTH sides believed they were “furthering the cause and ideals won during the Revolution of 1776.” Northerners believed the results of that Revolution were being perversely usurped, and at worst, overturned; and so those ideals, and the nation being arbitrarily dismantled, needed to be defended. Southerners believed they were merely “carrying out the logical extension of the Revolution, including overthrowing tyranny whenever and wherever it is discovered.” The diary of Sarah Wadley, entry of 16 FEB 1861, clearly reveals the Southern mindset: “Father brought us some newspapers from which we learned that Jeff Davis of Mississippi and Alexander Stephens of Georgia have been elected President and vice president of the Southern confederacy, formed of all the seceding states. I had almost written the United States… how sad to think that we are united no longer, that we are no more natives of one common country, necessary as is the separation, how can we think of it without grief. I am glad that there has been a good choice of rulers made, both the president and vice president are said to be wise, upright and moderate men, all southerners know of their eloquence and experience in public life.” A few months later, with the Confederate Army having achieved victory at Bull Run, Sarah added (diary entry of 28 July): “President Davis’ message is all that we could have hoped from our hero statesman. Wise, moderate, and just in council, cool, brave and gallant in battle; firm, energetic and instant in the performance of his executive duties, truly we have in him a second Washington…”