“Civil War Hero Cuts His Throat”: Suicide Among Union Brevet Brigadier Generals and Colonels

In his pioneering study Shook Over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War, Dr. Eric T. Dean, Jr. provides Brevet Brigadier General Newell Gleason as an example of a Union brevet brigadier general who suffered from the psychological consequences of service during the war. Gleason appeared to be “nervous and excitable” following the Battle of Chickamauga, and his condition only deteriorated. In 1874, he was admitted to Indiana State Hospital for the Insane and took his life by jumping headlong down a flight of stairs. But Gleason was no anomaly when it came to Union brevet brigadier generals or colonels who committed suicide to end their psychological or physical suffering.[1]

As mentioned in a previous post, the number of Union brevet brigadier generals and colonels who were either institutionalized or took their own lives by various methods (over 40) is alarming. The alleged “causes” for suicide included financial misfortune or ruin, the death of a loved one(s), guilt or shame, poor health, alcohol abuse, or war trauma and war injuries — or a combination of more than one of these factors. As. Dr. Diane Miller Sommerville indicated in her groundbreaking book on suicide and suffering in the Civil War-era South, “Motivations for those undertaking voluntary death are complicated, multilayered, and largely obscured,” making it unlikely that a historian can identify with certainty why a subject committed suicide. Witnesses, coroners, family members, or even the victims attempted to determine a motive, but we can’t be certain of every factor that played a role in the victim’s demise.[2]

Wartime experiences are not given as a reason why most of these brevet brigadier generals and colonels committed suicide, but they are for some. The four cases below (one during the war, one immediately after the war, and the other two decades after it ended) were attributed to war trauma, war injuries, or humiliation during the war.[3]

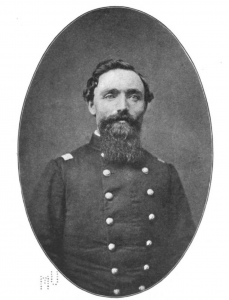

Colonel Matthew Schlaudecker

Born in Rülzheim, Bavaria, in 1831, Matthew Schlaudecker received training as a military engineer before relocating to Erie, Pennsylvania, during the 1850s. He joined the Pennsylvania militia, and by the outbreak of the Civil War, he reached the rank of major general. When President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers, Schlaudecker recruited three companies and was appointed major of the short-lived Erie Regiment. After its three-month term expired, Schlaudecker was mustered out and was appointed lieutenant colonel of the 111th Pennsylvania Infantry in September 1861.

By the end of January 1862, Schlaudecker took command of the regiment and was appointed colonel. He was instrumental in whipping the green Pennsylvanians into fighting shape, but he never had an opportunity to lead them into any of the Army of the Potomac’s key battles. A bout of typhoid fever caused him to remain bedridden and to miss Antietam. Schlaudecker took command of a brigade in the Army of Virginia in August 1862, but his continued poor health led to his resignation at the beginning of November.

The soldiers of the 111th never forgot the impact Schlaudecker had on them in the early days of the war. “No more efficient field officer in the camp or on the drill ground could be desired, and the command parted from him with genuine regret,” one soldier of the regiment lamented. “He was to be no longer among us, but his interest in the regiment never ceased, and his friendly hand was always open to any of it members.” Many who entered the war with Schlaudecker perished by its conclusion. Among them was Lieutenant Colonel George A. Cobham, Jr., who succeeded him in command of the 111th Pennsylvania Infantry. He was killed at Peachtree Creek in July 1864.[4]

By the end of February 1863, Schlaudecker felt his health had improved enough to seek a commission as a brigadier general from President Lincoln. Despite receiving accolades from Generals John A. Dix, John W. Geary, and Franz Sigel, he never received it or returned to the field.[5]

After his wife’s passing, Schlaudecker moved in with his daughter Ida. On the morning of September 20, 1907, Schlaudecker failed to appear for breakfast by 9 a.m. Ida sent her daughter-in-law, Odella, to check on him. Odella found the elder Schlaudecker lying on the floor. He had cut his throat with a razor. The walls, mirror, and furniture were spattered with his blood. The razor Schlaudecker used to kill himself was neatly placed on a table.

Newspapers attempted to determine the veteran’s motive for taking his life in such a brutal manner. The San Francisco Call reported the day after Schlaudecker’s death, “It is supposed that the act was done during a moment of temporary aberration, as no other cause for the deed has been discovered.” On the same day, the San Francisco Chronicle alluded to Schlaudecker suffering from war trauma. “Since the fire he has brooded over losses,” the paper declared, “and this is thought to have affected his mind.” Was Schlaudecker haunted by the memories of his comrades of the 111th who had died during the war? Or did the newspaper’s editors manufacture a motive? Unfortunately, we will never know for sure. The coroner simply ruled Schlaudecker’s death as “suicide while insane.”[6]

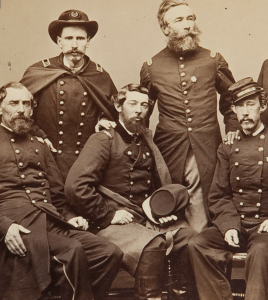

Colonel John Fredrick Cramer

John Frederick Cramer was born in Eschwege, Germany, in 1830, and migrated to St. Louis, Missouri, where he became a dry goods merchant. He was appointed a captain in the 3rd Missouri Infantry in May 1861, and his younger brother Gustav (who later became a noted photographer) was made a sergeant in his brother’s company. Both brothers served for three months until the regiment was mustered out in September. Gustav left the army to pursue his photographic pursuits but John stayed on and was appointed a lieutenant colonel in the 17th Missouri Infantry (or the Western Turner Rifles) in December. Following the skirmish near Searcy Landing, Arkansas, on May 19, 1862, where two companies of the regiment were enveloped by the enemy and overwhelmed, Colonel Peter J. Osterhaus praised “the gallant conduct exhibited” by Cramer. “[He] had command of reinforcements, which he conducted in a military and successful manner,” Osterhaus declared, “driving the enemy and relieving our friends.” By July 1863, Cramer succeeded Colonel Francis Hassendubel in command of the regiment, who had died of wounds received at Vicksburg.[7]

On May 2, 1864, while encamped with the regiment at its winter quarters near Bellefonte, Alabama, Cramer suffered a mental breakdown. Assistant Surgeon Charles Bruckner noticed that day that Cramer seemed particularly downcast. “I thought that it was nothing serious, because it was the first time that Cramer was sober for nearly two weeks,” he observed. “[H]e spoke about the 32nd Mo. Vol. Infty. crying ‘hang him up etc. etc., that’s meaning me.’” Perhaps this animosity was generated as a result of the bloodletting at Ringgold Gap on November 27, 1863, or some other episode. Either way, the humiliation Cramer received at the hands of these soldiers was too much for him to bear.[8]

Around 8 p.m., Major Francis Romer laid down to sleep in the tent he shared with Cramer. “Cramer then came and spoke out of his senses, fell asleep and I was woke up by his noise,” Romer recalled. About an hour later, perhaps to get some respite from Cramer, Romer left and headed to Captain Francis Wilhelmi’s tent, but Cramer followed close behind. “Cramer spoke for a while, and I noticed that he spoke unreasonable, out of sense, he spoke of the 32nd Mo. Vol. Infty. said, they would refuse to drill with him any more and he seemed to be afraid, that somebody might kill him,” Wilhelmi recalled.

Romer left Wilhelmi’s tent to get some sleep but Cramer followed close behind. He laid down to sleep a second time but about an hour later noticed that “Cramer got up took a revolver out of his revolver case and laid down on his bed, then snapped the pistol twice at me, [but] the pistol did not go off.” Cramer then said to him, “Hold on just wait a minute. This damned thing is not worth a damn. I’ll go get a better one.” Romer tried to hold Cramer back from leaving the tent but was overpowered. The panicked major then made his way to Captain John G. Langguth’s tent. Around 11 p.m., Romer woke up Langguth and told him Cramer was trying to kill him, so Langguth hid Romer under his blankets. Meanwhile, Cramer woke Private Henry Vornold and demanded a pistol, which the Prussian-born private handed over to him.

A single pistol shot shattered the tranquility of the camp. Langguth and Romer ran toward the sound of the gunshot and entered Cramer’s tent. Others gathered as well. Wilhelm held a light over Cramer’s lifeless body. Bruckner examined the colonel, opening his eyelids to see if he was still conscious. Two pistols lay by Cramer’s side — a single cylinder of one was missing a shot. “[O]n examining him [I] found a wound on his left breast,” Bruckner recalled. “[H]e breathed about 2 or 3 times and expired. The shot took effect a little below the left breast.” Gustavus Cramer received a telegram from Stevenson, Alabama, the day after announcing his older brother’s death, without giving any particulars, only that his brother’s body was on its way to St. Louis for burial.[9]

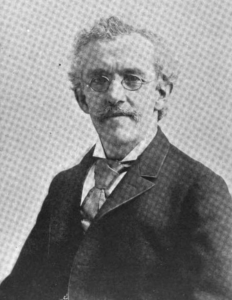

Colonel George G. Symes

Wisconsin lawyer George G. Symes enlisted as a private in the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry on June 11, 1861. He fought with the regiment at Bull Run in July, where he suffered a wound to the right hand and was discharged in November. Symes was appointed a first lieutenant in the 25th Wisconsin Infantry in August 1862, and then a captain in November 1863. On July 22, 1864, Symes was severely wounded in the left side at Decatur, Georgia. At the age of 24, he was made colonel of the 44th Wisconsin Infantry, allegedly making him the youngest Union officer to hold that rank at the time. Symes commanded the Post at Paducah in the Department of Kentucky from June until he was mustered out in August 1865.[10]

After the war, Symes resumed his legal career. In 1869, President Grant appointed him an associate justice of the Supreme Court for Montana Territory, but he resigned to practice law in Helen. Symes later relocated to Denver and was elected to Congress, serving two terms (from 1885 to 1889). He became one of Denver’s wealthiest and most notable citizens, with property valued at one million dollars.[11]

But the successful war veteran was a physically broken man by the age of 53. For 30 years —most of his life — he had suffered from his Decatur wound, which affected his spine and caused partial disablement. “[T]he wound gave to his bearing while on the street a stiffness which people, not knowing the cause, often ascribed to a false pride, or a false sense of dignity on his part,” the Salt Lake Tribune recorded. “[B]ut nothing could be further from the truth, for he was among men as approachable, as cordial and as appreciative of the abilities of other men as any man who ever lived.”

On November 3, 1893, a janitor knocked on the judge’s door while on his daily rounds. He did not receive an answer, so he inserted his key and entered the room, where he found Symes dead in a chair. A revolver lay in a pool of blood on the floor. The veteran’s wife and daughter had recently traveled to Massachusetts, providing Symes with the opportunity to end his life. Before shooting himself, Symes penned a letter to his wife. It declared that he was suffering from “a terrible attack of congestion of back and brain” and left detailed directions on how to handle his estate.

“Mr. Symes killed himself, presumably while laboring under pain so intense that his reason was temporarily affected,” the Daily Inter Ocean stated two days after his body was discovered. “He was wounded in the spine during the war and of late has suffered greatly and has been much depressed.” A friend insinuated that growing debt and financial losses contributed to Symes’ depression. The wealthy judge was interred at Fairmount Cemetery in Denver, Colorado. There is no indication on Symes’ headstone how he met his tragic demise.[12]

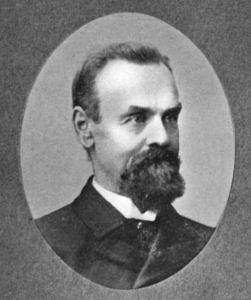

Colonel John M. Orr

The son of a War of 1812 veteran, John M. Orr was appointed a captain in the 16th Indiana Infantry in July 1862. This was followed by major in August and lieutenant colonel in November. Orr was wounded in the head by a shell fragment only 30 yards outside the Confederate works at Arkansas Post, Arkansas, on January 12, 1863. He survived, but Orr resigned that April noting that the wound “has impaired my hearing so much that it renders me totally unfit to perform the duties involved upon me as a field officer.” Despite his near-death experience and disability, Orr returned to the field eight months later and was appointed a captain in the 124th Indiana Infantry. He rose to the rank of colonel by July 1864 and commanded a brigade in the 23rd Corps at various times until the conclusion of the war.[13]

After being mustered out on August 31, 1865, Orr returned to Indiana, traveling to Connersville, where he considered starting a new life. On the morning of September 27, Orr headed to the market. After returning home he went to the outhouse and shot himself in the head. He reportedly did not exhibit any unusual behavior leading up to his suicide. The Lafayette Daily Journal had a theory of why he suddenly decided to end his life. “He was wounded at the battle of Arkansas Post, since which time he has occasionally been subjected to fits of mental aberration,” the paper stated, “and it is supposed that in one of these he put an end to his life.” Likewise, the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune said that the concussion of the shell and the wound caused Orr to suffer “periodical fits of partial derangement ever since, in one of which, it is believed, he did the fatal deed.” Orr was buried in the Connersville City Cemetery less than a month after he had been mustered out of service.[14]

Breaking Down the Numbers

We do not have the figures of Union brevet brigadier generals or colonels who contemplated suicide, attempted it (and failed), or deaths that were not ruled a suicide even though there might be evidence to prove otherwise. Also, some officers died under mysterious circumstances or disappeared that may have ended in suicide. (For example, as in the case of Brevet Brigadier General Henry B. Clitz who disappeared near Niagara Falls in 1888.) But even with these gaps in the data, what is available is revealing.

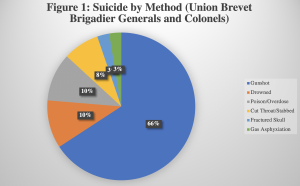

Not surprisingly, death by gunshot ranked the highest among the officers as the method of suicide (Figure 1). It remains the highest method of suicide among males today. This was followed by drowning (10 percent) and poisoning/overdose (10 percent).

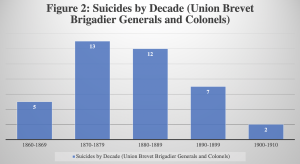

The greatest number of suicides took place during the 1870s and 1880s (Figure 2), 20 and 30 years after the war ended. Interestingly, there was a reported rise in suicides among the general population after the war. In her book Grief in Wartime: Private Pain, Public Discourse, Dr. Carol Acton notes one study that found that grief symptoms among modern veterans who lost a comrade were detected at high levels 30 years after they left combat. The level of intensity was comparable to grieving spouses and parents six months after the loss of a loved one. That is not to say all of these brevet brigadier generals and colonels were grieving war veterans, but it is something that may warrant further investigation.

Also worth noting is the change in the public’s attitude toward suicide after the Civil War. When it comes to the Civil War-era South, Sommerville found that suicide following the Civil War became more socially acceptable. There was greater empathy toward the victims than there was during the antebellum period. There is some evidence of this sentiment in the post-war North as well among the obituaries of these Union brevet brigadier generals and colonels.[15]

A Cry for Help

As Sommerville states, no historian can be sure why a victim committed suicide. There is likely more than a single factor involved. But contemporary accounts in all four cases examined above alluded to war service as a significant factor in these officers’ suicides. This demonstrates that senior Union officers, while allowed certain privileges common soldiers did not receive during the war, were equally susceptible to psychological and physical suffering as a result of their wartime experiences.

In his book Memory, War and Trauma, Dr. Nigel C. Hunt states that individuals deal with traumatic memories differently — some get on with their lives, and others are overwhelmed by them. Besides offering an escape from psychological trauma, veterans chose suicide (and still do) to relieve their suffering from war wounds or for other reasons. On average, 7,300 veterans commit suicide each year, but as has been revealed, this is an old issue among veterans as much as it is a modern one.[16]

Editor’s Note: If you know someone going through a difficult time or mental health struggles, we encourage you to seek help. One resource is the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

Endnotes

[1] Eric T. Dean, Jr., Shook over Hell: Post-Traumatic Stress, Vietnam, and the Civil War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), 151-53. Contemporary accounts claimed Gleason’s fall was an accident, not a suicide. “Fatal Accident to Gen. Gleason,” Kalamazoo Gazette (Kalamazoo, MI), July 9, 1886; Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago, IL), July 7, 1886.

[2] Diane Miller Sommerville, Aberration of Mind: Suicide and Suffering in the Civil War–Era South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018), 8; Diane Miller Sommerville, “‘A Burden Too Heavy to Bear,’ War Trauma, Suicide, and Confederate Soldiers,” Civil War History 59, no. 4 (December 2013): 459.

[3] The author is indebted to author Roger D. Hunt for his meticulous research in his Colonels in Blue book series and Brevet Brigadier Generals in Blue (Gaithersburg, MD: Olde Soldier Books, 1990). Hunt lists many officers who committed suicide in these books, but he left some out. Therefore, some brevet brigadier generals and colonels may be missing from this study. Hopefully, further research on the subject will remedy this oversight.

[4] Roger D. Hunt, Colonels in Blue Union Army Colonels of the Civil War: the Mid-Atlantic States: Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware, and the District of Columbia (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003), 146; John R. Boyle, Soldiers True The Story of the One Hundred and Eleventh Regiment Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers and of Its Campaigns in the War for the Union, 1861-1865 (By John Richards Boyle, Published by Authority of the Regimental Association, 1903), 11-12, 39, 68.

[5] All of this correspondence related to Schlaudecker seeking promotion to brigadier general can be viewed on Fold3. Brigadier General John W. Geary to Colonel Matthew Schlaudecker, Bolivar, VA, November 14, 1862; Major General John A. Dix to Colonel Matthew Schlaudecker, Fort Monroe, VA, November 10, 1862; Rep. Elijah Babbitt to President Abraham Lincoln, Washington, D.C., February 27, 1863; Sen. Marrow B. Lowry to President Abraham Lincoln, Harrisburg, PA, January 19, 1863; Major General Franz Sigel, Gainesville, VA, November 8, 1862.

[6]“A Soldierly Tribute,” San Francisco Call Bulletin (San Francisco, CA), June 2, 1896; “Finds Man Dead Whom She Would Call to Breakfast,” San Francisco Call (San Francisco, CA), September 21, 1907; “Civil War Hero Cuts His Throat,” San Francisco Chronicle (San Francisco, CA), September 21, 1907; “California, San Francisco County Records, 1824-1997,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-95F3-9ZQF?cc=1402856&wc=319R-4WR%3A20726101%2C32676502: 16 May 2016), Coroner’s Records > Death Register, 1906-1912 > image 59 of 400; San Francisco Public Library, California; “California, San Francisco County Records, 1824-1997,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-95F7-9HF2?cc=1402856&wc=319R-K6D%3A20726101%2C36748301: 13 May 2016), Coroner’s Records > Death Reports, September 1907 > image 116 of 239; San Francisco Public Library, California.

[7] Roger D. Hunt, Colonels in Blue—Missouri and the Western States and Territories A Civil War Biographical Dictionary (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc. Publishers, 2019), 11; “Death of Col. Cramer,” Daily Missouri Republican (St. Louis, MO), May 5, 1864; “United States Census, 1860,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GBS4-NB4?cc=1473181&wc=7Q3P-D91%3A1589429312%2C1589430131%2C1589430909: 24 March 2017), Missouri > St Louis > Town of Carondelet > image 50 of 192; from “1860 U.S. Federal Census — Population,” database, Fold3.com (http://www.fold3.com: n.d.); citing NARA microfilm publication M653 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); Walter Barlow Stevens, St. Louis, the Fourth City, 1764-1909, Vol. 2 (Chicago-St. Louis: The S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1909), 198-200; “Death of ‘Papa’ Cramer,” in Bulletin of Photography, Volume 15, July 1 to December 20, 1914, Frank V. Chambers and John Bartlett, eds. (Philadelphia: Frank V. Chambers, Publisher, 1914), 132-33; “The Army of the South-West, and the First Campaign in Arkansas,” in The Annuals of Iowa, Vol. 7—1869, Sanford W. Huff, ed. (Davenport, IA: Griggs, Watson and Day, Printers, 1869), 130; The Union Army: A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States 1861-65 — Records of the Regiments in the Union Army — Cyclopedia of Battles — Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers, Volume V, Cyclopedia of Battles — Helena Road to Z (Madison, WI: Federal Publishing Co., 1908), 780.

[8] “No. 192. Report of Brig. Gen. Charles R. Woods, U.S. Army, commanding First Brigade, Ringgold, Ga., November 28, 1863,” in The Miscellaneous Documents of the House of Representatives For the Second Session of the Fifty-First Congress, 1890-91 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891), 606-609; “Report of Brig. Gen. Peter J. Osterhaus, U.S. Army, commanding First Division, Fifteenth Army Corps, Near Bridgeport, Ala., December —,1863,” in The Miscellaneous Documents of the House of Representatives, 589-606.

[9] A special thanks to Phil Hinderberger for helping the author fill the gaps about the 17th Missouri’s role at Ringgold Gap and Colonel Cramer. He also provided copies of “Regimental Correspondence—Personnel includes affidavits regarding the suicide of Lieutenant Colonel John F. Cramer” from, 133.21, Office of Adjutant General Infantry, Missouri Volunteers Regimental Returns, 17th Regiment Infantry, Missouri State Archives, Jefferson City, Missouri. “Death of Col. Cramer,” Daily Missouri Republican (St. Louis, MO), May 5, 1864; Daily Missouri Democrat (St. Louis, MO), May 5, 1864. A similar case that became widely known in India in the British Army was that of Lieutenant Colonel John Wallace King. John H. Rumsby, “Suicide in the British Army,” Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 84, no. 340 (Winter 2006), 355-56.

[10] Roger D. Hunt, Colonels in Blue—Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota and Wisconsin: A Civil War Biographical Dictionary (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc. Publishers, 2017), 267-68; “A Sensational Suicide: Hon. George Symes of Denver Shoots Himself,” Los Angeles Daily Herald (Los Angeles, CA), November 5, 1893; Will C. Ferril, ed., “Judge George Gifford Symes,” in Sketches of Colorado, Vol. 1 (Denver, CO: The Western Press Bureau Co., 1911), 371.

[11] “A Sensational Suicide: Hon. George Symes of Denver Shoots Himself”; Ferril, ed., “Judge George Gifford Symes,” 371; “In Memoriam: Colonel George G. Symes,” in Society of Army of the Army of Cumberland, Twenty-Fifth Reunion, Chattanooga, Tennessee, 1895 (Cincinnati, OH: The Robert Clarke Co., 1896), 165-66.

[12] “Took His Own Life: Suicide of George G. Symes, Formerly of Wisconsin, at Denver,” Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago, IL), November 5, 1893; “Shot Dead in His Chair,” St. Paul Daily Globe (St. Paul, MN), November 5, 1893; “A Pitiable Ending,” Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, UT), November 9, 1893.

[13] Roger D. Hunt, Colonels in Blue—Indiana, Kentucky and Tennessee: A Civil War Biographical Dictionary (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc. Publishers, 2014), 95-96; Jacob P. Dunn, Greater Indianapolis The History, the Industries, the Institutions, and the People of a City of Homes, Vol. 2 (Chicago: The Lewis Publishing Co., 1910), 893; “No. 8. Report of Brig. Gen. Stephen G. Burbridge, U.S. Army, commanding First Brigade, Port Arkansas, Ark., January 14, 1863,” in The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Additions and Corrections to Series I—Volume XVII (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1902), 730.

[14] “Suicide of Colonel Orr,” Lafayette Daily Journal (Lafayette, IN), September 30, 1865; “Reception of Cavalry—Suicide of Colonel Orr—A Doctor Arrested—He is Threatened With Lynching, & c.,” Cincinnati Daily Enquirer (Cincinnati, OH), September 29, 1865; “From Indianapolis,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribute (Cincinnati, OH), September 29, 1865; Chicago Tribune (Chicago, IL), September 30, 1865; Daily Richmond Whig (Richmond, VA), October 5, 1865; “Melancholy Suicide,” Fort Wayne Daily Gazette (Fort Wayne, IN), October 3, 1865. In “‘A Burden Too Heavy to Bear,’ War Trauma, Suicide, and Confederate Soldiers,” Dr. Sommerville writes (pg. 483), “Being wounded in battle could also propel a soldier into a debilitating downward psychological spiral resulting in institutionalization or even suicide.” Likewise, she notes (pg. 484), “Head trauma received in during battle might explain aberrant psychological behavior.”

[15] R. Gregory Lande, “Felo De Se: Soldier Suicides in America’s Civil War,” Military Medicine 176, no. 5 (May 2011): 531-32; “Suicide Statistics,” American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, https://afsp.org/suicide-statistics/; Carol Acton, Grief in Wartime: Private Pain, Public Discourse (Basingstoke, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 106-107; Sommerville, Aberration of Mind, 15-16.

[16] Nigel C. Hunt, Memory, War and Trauma (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 7-9; Yeganeh Torbati, “Suicide rate of U.S. veterans rose one third since 2001: study,” Reuters, August 3, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-veterans-suicides/suicide-rate-of-u-s-veterans-rose-one-third-since-2001-study-idUSKCN10E2RN.

A very illuminating and fraught discussion. Thanks for casting a light on this subject.

This is simply an excellent post. A well-researched and -analyzed summary of an important subject about which I knew little.

A topic equally true today. The rate of suicide among veterans is higher than the population as a whole.

Tom Crane