Recruiting the Crew: Iron Men for Iron Ships

Both Civil War navies faced severe recruiting shortages in that first war year and indeed throughout the conflict.

Both Civil War navies faced severe recruiting shortages in that first war year and indeed throughout the conflict.

The U. S. Navy expanded tenfold, competing for enlistees not only against the army but also alongside the burgeoning, more lucrative, and less dangerous merchant marine.

Land forces took priority in the South also, but unlike Yankeedom, the region cultivated few mariners to begin with. A revolutionary type of warship presented additional challenges.

The USS Monitor was hastily fitting out at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in January 1862, preparing to steam south and confront the ironclad ram CSS Virginia (aka Merrimack) before she destroyed the Union squadron in Hampton Roads, Virginia.

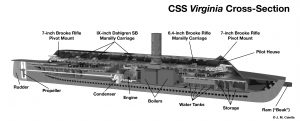

Monitor was a steam-propelled, iron-plated raft with a revolving cylindrical gun turret and two XI-inch Dahlgren smoothbores. The flat expanse of deck was barely a foot and a half above the surface. Her enclosed, cramped, artificial spaces—foreshadowing future submarines—were a radical departure from open decks and high rigging of a traditional man-of-war, and not a little intimidating.

Monitor’s commanding officer, Navy Lt. John L. Worden, recalled: “Here was an unknown, untried vessel, with all but a small portion of her below the waterline, her crew to live with the ocean beating over their heads—an iron coffin-like ship of which the gloomiest predictions were made, with her crew shut out from sunlight and the air above the sea, depending entirely on artificial means to supply the air they breathe. A failure of the machinery to do this would be almost certain death to her men.”[1]

Worden sought volunteers from warships in New York harbor. Addressing crews of the 74-gun ship-of-the-line USS North Carolina and the sailing frigate USS Sabine, he described the probable perils of passage and the certainty of combat. Many more enthusiastically responded than were required.

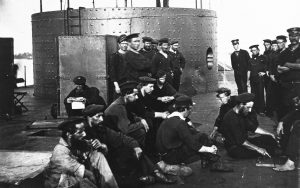

Fifty-five men constituted the crew. Senior enlisted petty officers included a gunner’s mate, master’s mate, master-at-arms, boatswain’s mate, and two quartermasters.

Seamen manned the guns and operated and maintained the vessel—anchoring, mooring, and managing boats and supplies. The numerous sail handlers of old were unnecessary.

Cooks, stewards, and servants performed their duties. Firemen and coal heavers kept steam machinery operating, receiving higher wages than seamen due to the discomforts involved and shortage of recruits. Worden’s nephew, Daniel Toffey, became his clerk.

Although a few of them had prewar sea service, most arrived as recent recruits. Previous occupations included farmer, machinist, carpenter, stonecutter, sailmaker, store clerk, or “none.” Some were immigrants: Scandinavian, German, Austrian, English, Scots, Irish, Welch. At least two were African American including one officer’s steward.

The volunteers endured ribbing from fellow seamen. In a “solemn and prophetic tone,” one old salt proclaimed: “You fellows certainly have got a lot of nerve or want to commit suicide, one or the other.” Several new crewmen took one look at the little ironclad and promptly deserted.[2]

In the meantime, Virginia’s officers scrambled to assemble a crew. The Rebel vessel (essentially a huge iron shed atop the hull of the former steam frigate USS Merrimack) was badly ventilated, uncomfortable, and unhealthy, noted Confederate Navy Lt. Catesby Jones, second in command. “The crew, 320 in number, were obtained with great difficulty,” mostly volunteers from various army regiments stationed about Norfolk. With 50 or 60 men in the hospital and others on the onboard sick list, the effective complement numbered about 250.[3]

“There was a sprinkling of old man-of-war’s men,” recalled Lt. John R. Eggleston, “whose value at the time could not be overestimated.” The few experienced seamen had deserted or resigned from the U. S. Navy to serve the South, including some petty officers—gunners, boatswain mates, and master’s mates.

Englishman Charles Hasker had been a Royal Navy seaman before immigrating to America. The rest “had never even seen a great gun like those they were soon to handle in a battle against the greatest of odds ever before successfully encountered.”[4]

The army reluctantly and at much urging from Navy Secretary Stephen R. Mallory allowed some transfers. Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder, commanding the Army of the Peninsula, offered 200 volunteers from his meager force.

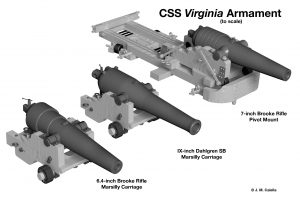

Captain Thomas Kevill and 39 men from the United Artillery, Company E, 41st Virginia Infantry Regiment—all trained artillerists and many with seafaring backgrounds—volunteered as a body. They manned one of Virginia’s IX-inch Dahlgrens and filled in on others.

Lieutenant Jones dispatched Lieutenant John Taylor Wood to handpick 80 of Magruder’s soldiers with seamanship or gunnery backgrounds, but when the chosen group arrived for training, all but two had been switched. “They are certainly a very different class of men from those I selected,” Wood reported to Secretary Mallory, who then complained to the secretary of war about lack of cooperation and substitution of castoffs. Some arrived chronically ill. Others came aboard in double irons under punishment for insubordination or other infractions.[5]

Jones immediately freed the miscreants saying he would have no forced volunteers. If they chose to remain, they would start fresh. “This course proved eminently judicious, as some of them were the best men on board,” recalled another lieutenant. They culled additional volunteers out of regiments stationed nearby from all over the South. One Virginian listed his prewar occupation as “comedian.”[6]

An army captain witnessing the scene recalled this “huge, unwieldly make-shift” craft steaming out “officered with the very cream of the old navy, and manned by as gallant a crew as ever fought in a good cause—Southern born almost to a man. . . .”

She was “freighted down to the very guards with the tearful prayers and hopes of a whole people,” fighting heroically against overwhelming odds that they might govern their own soil in their own way. “Every man and officer well understood the desperate hazards of the approaching fight; the utter feebleness of their ship, and the terrible efficiency of the enemy’s magnificent fleet. . . .” Many thought Virginia would sink with all hands enclosed in an “iron-plated coffin” as soon as she rammed a vessel. [7]

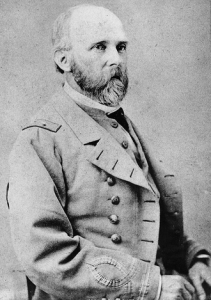

Virginia sallied forth into Hampton Roads on March 8, 1862, under the command of Flag Officer Franklin Buchanan. Murderous fire from numerous cannons ashore and afloat bounced off. She rammed and sank the 24-gun USS Cumberland and obliterated the 52-gun USS Congress with heated shot. Virginia suffered superficial damage with 2 killed and 19 wounded. That evening, Monitor slipped into harbor, and on the morning of March 9, the two faced each other.

Preparing for battle, Lieutenant Worden reminded his men that they all had volunteered. But having seen what Virginia was capable of and considering the fate of Cumberland, did any regret joining? If so, they would be sent off the ship. The crew leaped to their feet and gave three cheers. Not one took the offer. At 7:20 a.m., Worden piped all hands to quarters and got underway. “Our fastenings were cast off, our machinery started, and we moved out to meet [Virginia] half-way. We had come a long way to fight her, and did not intend to lose our opportunity.”[8]

Monitor’s Paymaster William F. Keeler recalled to his wife: “We were enclosed in what we supposed to be an impenetrable armour—we knew that a powerful foe was about to meet us—ours was an untried experiment & our enemy’s first fire might make it a coffin for us all. . . . The suspense was awful as we waited in the dim light expecting every moment to hear the crash of our enemy’s shot.”[9]

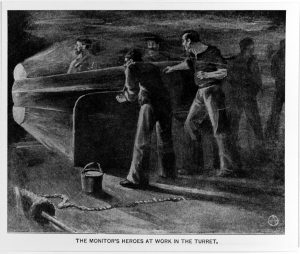

In the whirling turret, Acting Master Louis N. Stodder incautiously leaned against the bulkhead just as a Rebel shot whanged against the outside flinging him clean over the guns to the deck, knocking him senseless, and injuring his knee.

Seaman Peter Trescott’s head was only inches from the point of impact. “I dropped like a dead man,” he recalled. Both were carried below where the ship’s surgeon administered stimulants and applied cold presses. They recovered fully by the following morning, the only battle casualties among the crew. [10]

Virginia‘s Lieutenant Wood reported: “Again [Monitor] came up on our quarter, her bow against our side, and at this distance fired twice.” Both shots struck halfway up the shield near the aft pivot gun, humping the four inches of iron and two feet of oak and pine backing inward two or three inches. “All the crews of the after guns were knocked over by the concussion, and bled from the nose or ears. Another shot at the same place would have penetrated.”[11]

Monitor and Virginia pounded each other ineffectually for four hours, ending in a standoff. “A better [crew] no naval commander ever had the honor to command,” Lieutenant Worden recorded in his after-action report.[12]

Flag Officer Buchanan reported: “The bearing of [Virginia’s] men was all that could be desired. Their enthusiasm could scarcely be restrained. During the action they cheered again and again. Their coolness and skill were the more remarkable from the fact that the great majority of them were under fire for the first time. They were strangers to each other and to the officers, and had but a few days’ instruction in the management of the great guns.”[13]

On May 11, 1862, Union forces recaptured Norfolk and the Gosport Naval Yard, leaving the CSS Virginia with no home. She was blown up by her own crew. The USS Monitor sank in a terrible storm on December 31, 1862, 15 miles south of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Four officers and 12 crewmen were lost. The remaining crews of both warships went on to other service.

From Dwight’s new ECW Series volume Unlike Anything That Ever Floated: The Monitor and Virginia and the Battle Hampton Roads, March 8-9, 1862.

[1] John Worden, “The Monitor’s First Trip,” Youth’s Companion, Aug. 15, 1895, Frank H. Pierce Papers, New York Public Library, New York, in Mindell, Iron Coffin, loc. 1542-1546 of 4524, Kindle.

[2] Irwin Mark Berent, The Crewmen of the USS Monitor: A Biographical Directory (Raleigh, North Carolina: Department of Cultural Resources, 1985), 30 in John V. Quarstein, The Monitor Boys: The Crew of the Union’s First Ironclad (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011), loc. 603 of 6387, Kindle.

[3] Catesby ap Roger Jones, “Services of the Virginia,” in Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 11 (January-December 1904), 66-67.

[4] Captain Eggleston, “Captain Eggleston’s Narrative of the Battle of the Merrimac,” in Southern Historical Society Papers, 52 vols., vol. 41 (September 1916), 168.

[5] S.R. Mallory to J.P. Benjamin, January 25, 1862, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, 2 series, 29 vols. (Washington, D.C., 1894-1922), series 2, vol. 2, 137. Hereafter cited as ORN.

[6] Lewis Hampton Jones, Captain Roger Jones of London and Virginia: Some of His Antecedents and Descendants (Albany, NY, 1891), 267.

[7] William Norris, “The Story of the Confederate States Ship ‘Virginia’ (Once Merrimac.) Her Victory Over the Monitor,” in Southern Historical Society Papers, vol. 42 (September 1917), 206.

[8] Lieutenant Worden, “The Monitor and the Merrimac” in Lieut. J.L. Worden, U.S.N., Lieut. Greene, U.S.N., H. Ashton Ramsay, C.S.N., The Monitor and the Merrimac: Both Sides of the Story (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1912), loc. 90-91 of 568, Kindle.

[9] William Keeler to Anna, March 6, 1862, in Robert W. Daly, ed., Aboard the USS Monitor: 1862: The Letters of Acting Paymaster William Frederick Keeler, U. S. Navy to His Wife, Anna (Annapolis, MD, 1964), 34.

[10] William C. Davis, “The Battle of Hampton Roads,” in Harold Holzer and Tim Mulligan, eds., The Battle of Hampton Roads (New York: Fordham University Press, 2006), 13.

[11] John Taylor Wood, “The First Fight of Iron-Clads,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Being for The Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon “The Century War Series.” Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, of the Editorial Staff of “The Century Magazine,” 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), vol. 1, 703.

[12] S. Dana Greene, “In the ‘Monitor’ Turret,” in Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Being for The Most Part Contributions by Union and Confederate Officers. Based Upon “The Century War Series.” Edited by Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence Clough Buel, of the Editorial Staff of “The Century Magazine,” 4 vols. (New York, 1884-1888), vol. 1, 719.

[13] Buchanan to Mallory, March 27, 1862, ORN, series 1, vol. 7, 46.

thank you for the human angle to the crews. I never really thought about the unique staffing problems faced in filling out the ranks of these new ship designs

thanks Dwight, great essay … enjoyed the Battles and Leaders reference … you don’t see that much these days.

How many crew members did a typical Union tinclad have?