The Economic Challenges of the Confederacy

ECW welcomes back Dr. Lloyd W. Klein

Jefferson Davis brought to the Confederate Presidency long experience in the military and in politics, including service in the US Senate and the War Department. Nevertheless, he was not a very good executive. His challenge was to balance the state’s rights tradition with the necessities of creating a national government. This inherent conflict led to a staggering number of economic blunders that probably led as much to the downfall of the Confederacy as its military reverses. This essay explores several of the worst economic problems Davis faced and how he responded to them.

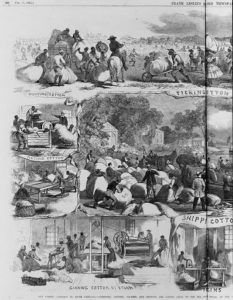

The Cotton Embargo

Davis’s decision to engage in a cotton embargo (to take cotton off the world market) was an attempt at economic blackmail. Before the war, cotton was the South’s most valuable crop, comprising 59% of the exports from the United States. For southern producers, the war disrupted both the production and marketing of what they presumed would be the financial basis of their new nation. In essence, Davis was engaged in blackmailing Great Britain to recognize the Confederacy. The plan backfired, resulting in an economic disaster for the South.

Confederate foreign policy depended on “cotton diplomacy”: its political leaders, many of whom were plantation owners, believed that artificial cotton shortages would secure diplomatic recognition and possibly military aid. The primary target of this policy was Great Britain, which consumed most of the output of the fiber in the textile mills of the Industrial Revolution.

In the summer of 1861, the Confederate government placed an embargo on cotton exports.

As late as January 1862, cotton traders in Liverpool held over a quarter million bales. Expectations of a swift resolution to the war shaped subsequent actions. Cotton factors and the planter class thought that Europe could not do without American cotton. Meanwhile the Confederacy’s shrinking borders and the loss of its ports and markets made them unreliable suppliers. The British instead began producing cotton in India.

As a result of the embargo, cotton production in the Confederate states decreased from about five million bales in 1860 to about one-quarter million in 1865. The Confederate government took control of cotton production in 1864, determining which plantations and planters could reap the profits.

The Bread Riots

In 1862, the Confederate Congress attempted to restrict cotton production in favor of domestic production of food crops. State governments tried to persuade their citizens and farmers to replace cotton production with food crops. The newspapers across the region promoted that goal in concert with the government, but the planters, who could, continued to produce their cash crop.

The Union blockade of Confederate ports markedly decreased food imports. Furthermore, food was becoming less plentiful because the farmers were now soldiers at war and because fighting had destroyed farmlands. As food became scarcer, prices increased to 10 times their prewar values.

The food shortage in Richmond had reached a critical point by Spring, 1863. In March, an unusually large snowstorm struck the city. The melting snow made muddy roads impassable, making it difficult to transport what little food was being grown on nearby farms. In addition, the city’s proximity to the war led to an overwhelming influx of wounded soldiers. And, as the government bureaucracy grew, the influx of civil servants and government staff placed further stress on an already inadequate food supply.

President Davis called for a day of fasting and prayer, on March 27, 1863. On April 2, 1863, riots erupted that were spawned by food deprivation. The Richmond Bread Riot resulted; it was the largest civil disturbance the Confederacy experienced.

On April 1, 1863, a rally of women mainly composed of ordnance workers and the wives of local ironworkers, met at the Belvidere Hill Baptist Church in Richmond to discuss the severe food shortage. The assembly decided to organize a march to Gov. John Letcher’s office to demand action. The next day, over 100 women took their complaints to Letcher. Despite brandishing axes, knives, and other weapons, the group initially remained calm, but Letcher had no solutions or promises of relief to offer. The irate assemblage marched to the government food storehouses, shouting “Bread! Bread!” and “Bread or blood!” As the march continued in the streets of Richmond, the size of the mob multiplied as additional armed citizens joined. The crowd swelled to hundreds, and likely thousands, of demonstrators. The alarmed governor called out the public guard, but they could not stop the rioters. Government storehouses and nearby businesses were broken into and looted as citizens grabbed all the food they could.

The bread riot was only controlled when President Jefferson Davis himself climbed on top of a wagon in the street and asked for peace. When that failed, he threatened to have Confederate troops open fire on the crowd. The riot was eventually subdued when Davis began to count to five, threatening to fire on his own citizens if quiet was not restored.

Inflation

The Confederate government initially issued bonds to finance the war, but widespread public investment never materialized. Taxes were lower than in the Union but collected with less efficiency. Both the Confederate government and individual states printed more and more paper money as the war continued. The result of printing paper money without money in the treasury to back it was runaway inflation. President Davis believed that under states’ rights, he had no authority to limit the states in producing currency, even if it unsecured.

Over-expansion of the money supply to this extent caused inflation to spiral out of control. When money supply expands, the value of the currency decreases. When currency declines relative to the value of foreign currencies, prices of foreign goods rises but domestic goods become cheaper. Consequently, the entire commodity market collapses.

Indeed, the value of Confederate money plummeted. Annual inflation increased dramatically: the annual inflation rate rose from an overwhelming 60% in 1861 to a devastating 300% in 1863 and then a crushing 600% in 1864. The Confederate commodity price index rose an average of 10 percent per month from October 1861 to March 1864. By the end of the war, the cost of living had increased 92 times compared to before the war.

At the beginning of the war, one Confederate dollar would purchase one US Gold dollar. By May 1861 it required another 5 cents, or 5% inflation in four months. By February 1862 it took $1.25 Confederate Dollars, or 25% inflation, and in February 1863, $3.00 Confederate Dollars, or 200% inflation since 1861 or 140% if inflation is calculated annually.

Ultimately, it was the inflation of Confederacy currency that led to the food riots. One apocryphal story was that you had to use a wheelbarrow to take your money to market and only a basket to bring your purchases home.

In February 1864, the Confederate Congress instituted effective currency reform. Paper currency with a value greater than five dollars was to be converted into bonds paying 4 percent interest. All bills not converted by April 1 were to be exchanged for a new issue at a ratio of 2 for 3. Prior to the commencement of the reform, people spent wildly and drove prices up 23 percent in one month. The reform was completed in May 1864 and the money supply was reduced by one-third. The general price index declined and the value of the confederate dollar stabilized until the end of the war.

The Salt Famine

Prior to the Civil War, the South consumed an estimated 450 million pounds of salt annually. The antebellum South produced very little salt; most was imported from Wales by ship, which carried salt as ballast. In the 1800s, salt was used for numerous manufacturing purposes, such as tanning leather for use in making harnesses and shoes. Additionally, salt was used as a food preservative. Since there was no refrigeration, all uncooked pork and beef was either served immediately after slaughter or preserved in brine. Ships could not import salt into Southern ports once the blockade was initiated. New Orleans had large stockpiles of salt, but this accumulation had become depleted by the fall of 1861. Salt prices surged with the scarcity; farmers who raised hogs were unable to preserve them. Facing severe shortages by 1862, Southern leaders encouraged domestic salt production. A “salt famine ” ensued.

Although Saltville, VA allowed Virginia to have relatively good salt supplies for most of the war, there was a real shortage elsewhere. Georgia and Florida asked their governors to take control. The Confederate government panicked, and started giving out rewards for domestic salt production.

Union leaders recognized that the salt shortage could win the war. “What good could it do to destroy salt?” the United States Navy admiral David Dixon Porter asked 20 years after the war. “It was the life of the Confederate army … they could not pack their meats without it. A soldier with a small piece of boiled beef, six ounces of corn-meal, and four ounces of salt, was provisioned for a three-day march.” Preserving meat was a huge problem for supplying armies: salted beef and pork were staples for soldiers and civilians alike.

Salt manufacturing areas became military targets. The Union forces targeted and destroyed salt production facilities, with former slaves often leading them to salt-making cauldrons hidden in swamps. The Kanawha Valley in Virginia and Goose Creek in Kentucky were targeted and captured early in the war. In Louisiana, the Union army seized New Iberia and took control of Avery Island in 1863. Saltville was regularly targeted, and was finally captured in December 1864.

Dr. Lloyd W. Klein is Clinical Professor of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco. He is a nationally recognized cardiologist with over thirty-five years’ experience and expertise. He is also an amateur historian who has read extensively and published previously on the Civil War, with a particular interest in political and military leadership and their economic ramifications.

References:

- “Look Away” by William C Davis. Chapter 10. The Free Press, 2002, Simon and Schuster.

- Battle Cry of Freedom by James McPherson.

- Cotton and The Civil War. Eugene Dattel. http://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/articles/291/cotton-and-the-civil-war

Amazing to me that the Confederacy was able to last as long as it did given the huge disadvantage that its small population and agrarian economy.

Thanks for reading and for you comment. Perhaps they might have lasted longer with better executive management? We will never know.

It makes me wonder how confident the Union and Confederacy were in the eventual victor. An army without food, clothing, and other supplies isn’t much of an army.

Thanks for your comment. I think no one seriously considered these matters because they thought the war would be over in 6 months.

Another valuable report, Thank-you. And hoping you have found an opportunity to investigate Charles Prioleau; Fraser, Trenholm & Company; Committee for the Relief of Southern Prisoners (Liverpool Chapter); Southern Club of Liverpool; Emile Erlanger & Company of Paris; Georgina Walker; Mozley Family; capture of the Benjamin F. Hoxie… just a few of the players involved and efforts exerted in supporting and funding the Confederacy. And counterpoint, Sam Upham as example of economic warfare against the CSA.

These are great point, maybe I will add them in another post! Thanks for your interest.

Thanks for another very informative article Dr. Klein! Another thing that seriously hurt the Confederacy was the distribution of counterfeit Confederate currency by Daniel C. Upham, a businessman from Philadelphia. For anyone having any Confederate bills, are you sure they weren’t printed by Mr. Upham?

Thanks for this comment. Yes, counterfeit confederate bills may well have played a part, but I don’t think the Davis government understood monetary policy anyway.

Fascinating post.

Thanks for reading!

I tend to agree Jefferson Davis wasn’t the greatest chief executive a government could have (he literally can be blamed for every failure), but he and other officials managed to keep the Confederacy going for a full four years against all odds. On paper and in reality, Jefferson Davis was probably the best man the Confederates had to lead them. He was a competent politico and was one of the leading American Congressman of the post-Mexican war and pre Civil War period. Unlike President Lincoln, Jefferson Davis chose to travel around the Confederacy throughout the war to maintain the rebel cause, which proved successful in that it could have collapsed sooner with the many Confederates setbacks out West. He seems to have been warmly received by Confederate soldiers all the times he visited them in the field.

As far as the above economic predicaments the Confederates chose to burden themselves with, I can’t fault him for the poor economic policy when nobody in his day had a good grasp of economic policy. He chose the path the leaders of the cotton class wanted to go down and they read their economic position wrong. Secession itself proved to be the worse economic decision the cotton class made. He personally handled the Richmond bread riots and maintained the peace. The currency situation wasn’t going to be handled by the best of Confederate minds, which in German-born Christopher Memminger they weren’t lacking. And of course up until the very end the Confederates were able to keep their armies fed somehow despite their limited salt production means.

Thanks for reading and your excellent comment. I think the counter argument is my post earlier this week expanding on the actions Lincoln, Chase, Cooke et al took.These problems did not affect the north. I hope that my criticism of Mr Davis is understood as recognizing the very serious problems anyone would face taking on a job like that. But, I maintain that he didn’t really do much to solve them until way too late. And his government, conflicted by the states rights philosophy, didnt have the foundation to deal with them.

I just went off on my own tangent about Jefferson Davis as a chief executive. There is so much to criticize, but the Confederacy put up quite the fight. I waffle on how to describe what happened in a limited amount of words.

I don’t disagree with you about the Confederacy’s economic malfeasance or the Union’s sound economic management. The northern economy was more balanced between industry and agrarian than the seceding slave states, there were more people, they had all the shipping stock, and therefore were significantly more stout financially. The Union economy was a modern economy. The Confederacy, on the other hand, was a proto-banana republic of cotton.

In hindsight, it’s clear the Confederacy wasn’t going to solve their self inflicted economic woes while in rebellion against the United States. Davis knew the war had to be managed by a national Confederate government, but he also had to respect, as you have said, the states rights politics of the Confederate people, which would hamper the war’s management from Richmond.

thanks Dr. Klein — great post

you have illustrated the poverty of the planter elite’s assumptions about the Confederate nation’s ability to sustain their economy and their population. As you point out, it took Britain about a year or so to figure out alternate sources for cotton. On the homefront, 85 percent of young white males in were in the army, and the yeoman farm country were stripped of their providers and soldier’s families were left to starve.

In another stunning display of hubris, they counted on the full cooperation of slaves (40 percent of the Southern population) and the enthusiastic assistance of slave owners. Supposedly, slaves would operate the South’s agricultural economy; they would build fortifications and conduct logistics for the army; and, the planters would happily release their “property” to support the war effort. Of course, the CSA immediately encountered slave and slave owner resistance. Slaves challenged efforts to impress them; they cleverly abstained from work on fortifications; and, they deserted to Union lines by the hundreds of thousands. Likewise, slaveowners unconditionally refused to release their slaves to support the war, or they actively colluded with slaves to avoid their impressment.

Ultimately, the South’s nation-state experiment was crushed by Northern military might. But its defeat was hastened by the illogical assumptions of the Confederate founders about the economic viability of their “republic.” The Confederacy clearly entered the war on a shaky foundation.

Thanks for your excellent comment. The southern economy was based on its labor management system, which was not sustainable long term. Had they achieved independence it’s not clear how they would have managed going forward. There only x amount of agriculture and cotton.

I’ve always wondered, if the Confederacy also adopted protectionist policies like “high tariffs” during wartime, would it prolong the life of the Confederacy? While I know low tariffs have always been the goal of the Confederacy, it’s absurd to insist on this in the face of an economic crisis