Destroyed Lives, Destroyed History – Historic Preservation and Natural Disasters

Through the night of December 10, 2021, over thirty tornadoes touched down in six states across the Mississippi River valley, from Arkansas to Kentucky. Reports estimate that over one hundred people died tragically in these storms, mostly in Monette, Arkansas; Edwardsville, Illinois; and Mayfield, Kentucky. Communities were leveled and livelihoods were destroyed in a matter of minutes.

Living in Missouri – where we do get hit by tornadic weather and have some of the deadliest tornadoes in U.S. history – and being a historic preservationist, I naturally get concerned for the historic structures at risk during severe weather events or other natural disasters. From tornadoes to wildfires, countless historic buildings, memorials, and museums have been damaged or destroyed by these catastrophic events. Once they are gone, we lose that tangible connection to the past and the historic character of a community.

Having been awake from the severe weather and tornado warnings in St. Louis that night, I stayed glued to the television, trying to get updates on the damage in the metro area, as well as the breaking news about a massive wedge tornado that swept through four states. Almost immediately after it had passed through the small, historic town of Mayfield, Kentucky, I saw a picture that made my jaw drop.

The beautiful historic 1888 Graves County Courthouse had sustained catastrophic damage. At first, I thought it was just the roof that collapsed. However, I did some research about the building and saw that it had a Victorian tower atop its roof that rose above the town of Mayfield. It was now just a hole in the roof. That Courthouse was a symbol of history and town pride for the community. It was not just the Courthouse that sustained significant damage. Mayfield had a quaint historic district listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Countless historic buildings in town are now rubble.

How much local history – and personal memories for its residents – was just destroyed?

We have seen the same happen across the country. In 2019, Missouri’s capital city Jefferson City was struck by an EF-3 tornado that swept through its historic district. The next year, the east side of Nashville, Tennessee was hit by a tornado, which damaged dozens of historic structures, including the 1859 Catholic Church of the Assumption. That church is still under renovation, because of the extent of the damage. In Marshalltown, Iowa, the historic Marshall County Courthouse building from the 1880s lost its cupola during a 2018 tornado. Some of these structures and monuments have been restored, but many others have been demolished or destroyed.

In regard to Civil War-related structures, how could any of us forget the toppling of the Rhode Island Monument at Vicksburg National Military Park in a 2019 tornado? Jefferson Davis’ home Beauvoir was significantly damaged in a tornado that spawned from Tropical Storm Cindy in 2017. A Civil War-era barn, known for being one of Michigan’s last hip-roofed barns, was completely destroyed in a 2019 tornado. Many of us also know the story of the historic Dunker Church at Antietam, which was toppled in a storm in 1921, but later rebuilt.

What do we as historians and preservationists do about the protection and perpetual care of these structures? We cannot control the weather, we cannot stop a tornado or hurricane from destroying a building or monument. However, we can prepare.

In Protecting Historic Architecture and Museum Collections from Natural Collections edited by Barclay G. Jones, a plan of preparedness for historic buildings and artifact collections is laid out. First, any group of property owners or an organization overseeing historic artifacts or properties must survey their current inventory. Inventories are “essential” and “must exist at least in duplication.”[1] After the survey and finding the issues with this documentation, organizations or owners must update, correct, and detail the inventory. Specifically, documenting structures with photographs, measurements, and duplicating blueprints. According to Protecting Historic Architecture, “careful records and documentation may permit extensive conservation or restoration in situations which would otherwise represent complete loss.”[2] Third, it is imperative to establish risk avoidance measures to reduce the threat of exposure to various environmental hazards: tornadoes, flooding, hurricanes, et cetera. To protect historic structures and/or artifacts, it is recommended that “careful scheduling, relocating objects, shuttering openings, bracing and other actions at particular times may avoid risk.”[3] The next, and considered “the most complex, technical, involved and potentially costly” part of this plan, is actively protecting the structure or artifacts.[4] This includes reinforcing the structure in ways that protect its structural integrity and do not infringe upon its historic features; fire suppression systems; updated security systems; temperature and humidity controls; and protective storage that reduces the risk of damaging items in a natural disaster. The fifth is having procedures during the emergency itself. Sometimes, institutions have minutes to respond, while in other situations, they have hours or days. Having short-term and long-term preparedness plans in place allow organizations or individuals to respond quickly and efficiently to any disaster that may arise. This is just one example of a preparedness plan that can be utilized to protect these structures or artifacts in a natural disaster.[5]

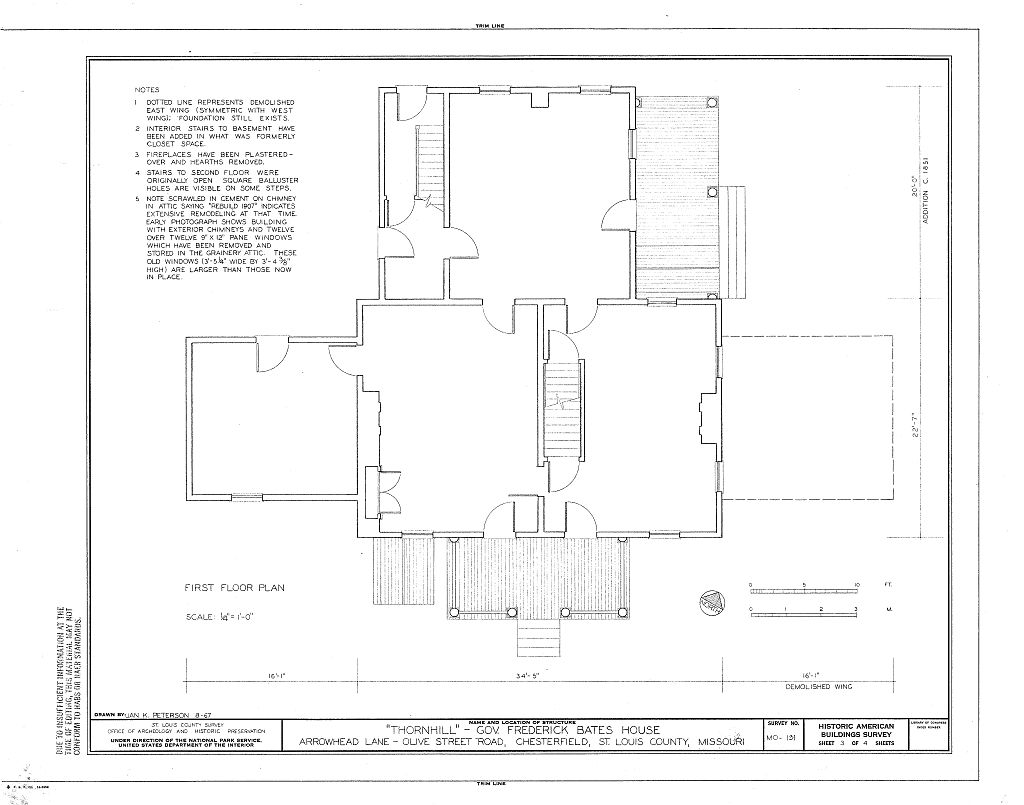

For documentation of historic buildings, the Department of the Interior and National Park Service operates the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) that documents the history and blueprints of historic structures. Fortunately, for major historic and government-owned sites, they adhere to the standards of HABS, but small historic communities may have never documented their buildings before. Sadly, Graves County, Kentucky (Mayfield is its seat) has no HABS report documentation. In 2019, the 1834 J. Huston Tavern in Arrow Rock, Missouri (the oldest continuously-operating restaurant west of the Mississippi River) sustained a major fire in its historic kitchen. Yet, because the building had a HABS report completed in 1934, was well-documented, and had a support base, the J. Huston Tavern was saved.

In addition to the above advice, the National Trust for Historic Preservation (NTHP) contains articles about how to protect your historic property – if you own a historic structure. Their advice is simple: “You can never be too prepared when it comes to protecting your historic property.”[6] The NTHP lists three major steps for protection: documentation, building maintenance, and risk transfer. Under documentation, they recommend preserving site plans and layouts, photographing the property extensively, keeping receipts and valuations, and making sure you have multiple secure copies of this information. It is also imperative to maintain electrical systems, plumbing, roofs, and HVAC. Finally, it is important to mitigate the risk involved with a property; this includes having proper insurance and working with reputable contractors.

For those who do not own a historic property, what can you do? Take pictures and research the historic buildings in your community. Then, make sure the information is duplicated and accessible to the community. You can also get involved in a local historical society, a preservation organization, or a museum.

In regard to Civil War-era structures, these catastrophic events should give us pause about the vulnerability of these buildings, artifacts, and memorials to natural disasters. In the Eastern Theater, where there are some of the largest and extensive Civil War sites in the country, there are threats of hurricanes and nor’easters that can cause tremendous water and wind damage. In the Western and Trans-Mississippi Theaters, tornadoes, severe storms, hurricanes, and earthquakes cause great risk to the many historic structures, museums, and memorials. As seen in numerous other examples, fire and flooding are risks for any building anywhere in the country. It is sadly a matter of “when,” not “if,” these catastrophic natural events will occur.

As historians and preservationists, it is imperative to plan and prepare for catastrophic natural disasters in order to save history. Once these buildings, memorials, and artifacts are gone, they are gone forever from the historical landscape. This is a call-to-action for us in the history community. Our sites, buildings, memorials, and artifacts are always at risk, but we can take steps now to make sure they have the chance to be saved.

Sources:

- Protecting Historic Architecture and Museum Collections from Natural Collections, ed. Barclay G. Jones (Boston: Butterworths, 1986), 181.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 182.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.,180-184.

- “How to Protect Your Historic Property,” National Trust for Historic Preservation, December 28, 2017, accessed December 16, 2021, https://savingplaces.org/stories/how-to-protect-your-historic-property#.YbuUXNbMKjg

Here in CA we have historic buildings as well, and we have fires, floods, and mudslides–plus the occasional earthquake. I was glued to the TV as well, and sending random prayers for all the history–and the historians–that were having to hold on tight back East. I will be printing off these ideas as my little city preps for the onslaught of high-density housing sprinkled in among the bungalows & Victorians.

The University of West Florida’s Historic Trust in Pensacola helps to preserve and maintain several historic homes in the downtown district. They have BOXES of architectural material about each house in the event of a disaster that requires restoration. The Dorr House (c. 1870s) had roof damage during one of the 2020 hurricanes, and they were lucky enough to be able to repair it without compromising the structure itself. It’s been inspiring to work with them and see how they tackle preservation of these buildings in a place that gets hit by hurricanes rather frequently.