The Priest, the Colonel, and the Cowboy’s Cousin

ECW welcomes back guest author Evan Portman

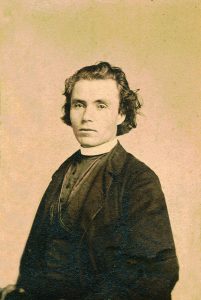

In the autumn of 1849, a bookish young Bavarian stepped down from a train in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, gazing at his new home: the newly established Saint Vincent Archabbey. The young man, 19-year-old Emmeran M. Bliemel, was so impressed by his teacher Rev. Boniface Wimmer at the Benedictine Gymnasium in Ratisbon, Bavaria that he decided to join Wimmer’s fledgling monastery in America. After being ordained as a priest and serving as a professor of mathematics at Saint Vincent College, the college established by Wimmer which adjoined the Abbey, Bliemel was sent south by Wimmer to serve the parishes of Covington, Kentucky. However, in the winter of 1859, Bliemel wrote his superior to ask for permission to work in Tennessee. Conveniently, Wimmer had recently received a plea from Bishop James Whelan asking to send priests to the Diocese of Nashville. It was there that Bliemel would go.[1]

It was also there that Bliemel witnessed the inauguration of civil war. Serving the Assumption Parish, the young German watched as his parishioners enlisted in Confederate regiments. Eager to serve the new Confederate nation, the pragmatic and realistic Bliemel became an outspoken Southern sympathizer. By February of 1862, Nashville became the first Confederate capital captured by Union troops. Bliemel’s zeal for the cause brought him to visit countless Confederate hospitals in the city during the Union occupation, administering aid and last rites to the wounded and dying.[2] That same zeal also got him into trouble. On the afternoon of December 11, 1862, Bliemel was gathering medical supplies to smuggle across Union lines to his Confederate friends encamped outside of Nashville. Federal authorities, tipped by an anonymous citizen, hid in waiting. After Bliemel emerged from a storefront, a Federal police officer followed him to a drug store and then the home of a prominent Nashville citizen by the name of Brant. After departing the residence, Bliemel finally returned to the store he had come from. There, the officer confronted the startled and bewildered Bliemel, who was caught in the act of retrieving four boxes of morphine.

The officer escorted the “genteelly dressed” and bespectacled priest back to the office of the chief of police, Colonel William Truesdale, for interrogation that evening. In a letter to Union Army of the Cumberland Commander Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, Truesdale recounted Bliemel’s argument in defense of his treasonous actions:

Have never taken any active part in this rebellion. Am a conservative Union man, would prefer the old Union as it was, but believe that the South had been deprived of rights which justified them in this rebellion. I paid $64 for the morphine & 1$ for some snuff and a comb, which were all together in the bundle. The latter article I bought at another store.

Bliemel also insisted that he had never been to Murfreesboro, the location of the Confederate Army of Tennessee.[3] Rosecrans, a converted Catholic, ordered the priest’s release. Six months later, though, Rosecrans once again found Bliemel in trouble, this time arrested and accused of writing for the Southern-sympathetic newspaper Freeman’s Journal. Fr. Bliemel again managed to escape conviction when Federal authorities found the true author.

While Bliemel was conducting treasonable business in Nashville, he became acquainted with the men of the 10th Tennessee Infantry Regiment, who listed him as an unofficial chaplain in October of 1862.[4] In the months during and following his arrests, the priest made repeated requests to Bishop Whelan to be transferred south so that he could join the 10th Tennessee in Georgia. Finally, in October of 1863, his pleas were granted. Procuring a horse and a recommendation from the Diocese of Nashville, Bliemel departed for Georgia and rode between Union and Confederate lines. He rendezvoused with the 10th Tennessee in their winter quarters in Dalton and was nominated officially as the regimental chaplain that January by the regiment’s colonel, William Grace. [5]

In the ensuing months, Bliemel followed the regiment in the Atlanta campaign, performing last rites for casualties at the battles of New Hope Church, Kennesaw Mountain, and Peach Tree Creek.[6] By late August, Bliemel and the 10th found themselves defending two railroads near Jonesborough against William Tecumseh Sherman’s effort to cut off Confederate supply lines and conquer the city of Atlanta. The Confederates arrived on the field outnumbered and outmaneuvered; two Union corps had seized the high ground west of Jonesborough and were well entrenched. As the Confederates began an uncoordinated assault, Union troops greeted the advancing infantry columns with a hailstorm of cannon and musketry fire. During the assault, Fr. Bliemel repeatedly exposed himself to this murderous fire as he stumbled behind the advancing columns with the litter bearers to offer aid and last rites to his fallen friends.

By 4:30 in the afternoon, however, the galling fire compelled the Confederates to fall back. In this retreat, the horrific rain of lead, which had not abated, pinned Bliemel to the ground. After witnessing his Colonel and friend William Grace fall with a mortal wound, the priest once again risked his life to offer his spiritual service in the Benedictine tradition. Bliemel knelt over his suffering friend and began the sacred Catholic rite of Extreme Unction. “Per istam sanctan unctionem et suam piissimam misericordiam,” he began, uttering the words in Latin and raising his hands in prayer. But before he finished, a shell fired from the Union position exploded near Bliemel, decapitating him. The priest’s headless corpse slumped over the wounded Grace.[7]

Fellow soldier Thomas Owens remembered, “We carried his body to the rear and reverently buried it in a grave a hundred yards or more southeast from the old stone depot at Jonesboro’.” Grace lived long enough to tell the tale of the courageous priest but died the following day while Confederate forces evacuated Atlanta. He was buried next to Bliemel.[8]

Those graves rested in the garden of the Hollidays, a prominent Catholic family from Jonesborough. The Holliday family, whose nephew was John Henry “Doc” Holliday, of later western fame, had fled to a neighboring plantation during the battle. Returning to the two fresh graves in their garden, the family vowed to take care of them. When the Daughters of the Confederacy established the Patrick Cleburne cemetery in Jonesborough, the Hollidays arranged for Colonel Grace and Fr. Bliemel to be moved there.[9] After tracking Bliemel’s remains to Jonesborough, Otto Kopf, one of Bliemel’s classmates and friends, arranged for the body to be moved to his parish in Tuscumbia, Georgia.[10] There it remains.

Emmeran Bliemel was the only Catholic chaplain killed during the war. His bravery has been noted by his contemporaries and historians alike. So too was his legacy carried by the Hollidays’ daughter, Martha “Mattie” Holliday, and his friends and confreres from Saint Vincent, whose monastic community continues to recognize his role in American history.

Evan Portman is a fledgling historian and continuing education instructor with the Penn-Trafford Area Recreation Commission, giving frequent lectures on their behalf. His interest and enthusiasm for Civil War history began with a trip to Gettysburg when he was seven years old and has grown ever since. He is currently pursuing a History major and secondary education minor at Saint Vincent College and will graduate in the spring of 2022.

[1] Rev. Dr. Brian Boosel, OSB, PhD, “Reverend Emmeran M. Bliemel, O.S.B., Monk of Saint Vincent Archabbey, Confederate Army Chaplain 1831-1864,” (Latrobe, Pennsylvania: Saint Vincent Seminary, April 29, 2003), 2-3.

[2] Aloysius Plaissance, “Emmeran Bliemel, O.S.B., Confederate Army Chaplain,” American Benedictine Review XVII, 2 (June 1966): 211.

[3] Abbey Archives, Saint Vincent Archabbey, Latrobe, PA.

[4] John B. Lindsley, The Military Annals of Tennessee, Confederate, (Nashville, 1886), 284.

[5] Plaissance, 213-214.

[6] Lindsley, 289.

[7] Peter J. Meaney, O.S.B. “Valiant Chaplain of the Bloody Tenth,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 41, no. 1 (Spring 1982): 45-46.

[8] Lindsley, 289.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Plaissance, 215.

Excellent post, Evan. I encountered Bishop Whelan during my research on Union General August Willich. Willich was captured at Stones River and held in a makeshift prison in Atlanta for several weeks. Whelan visited the captured Federal officers and was known to have strong sympathies for the Union cause. More studies of Civil War chaplains and their influence on the politics and piety of soldiers is always welcome. Thanks for sharing this story with us.

David: You make a good point. The only works I’m familiar with are the memoirs of William Corby CSC and Jim Schmidt’s Notre Dame and the Civil War, which is in the usual succinct History Press format but sheds some light on the role of ND’s founder, Edward Sorin CSC, in furnishing several chaplains to the Union armies (including Corby). While as an undergrad I was familiar with the Corby statue on campus (a replica of that at Gettysburg) as “Fair Catch Corby”, I did not know at the time of Sorin’s connections with the administration and that Corby wasn’t the only chaplain he provided to the Union. As an aside, you may be aware that Sherman’s wife and two of his children resided at ND during the war, apparently as a result of Sorin’s ties to her father, Senator Ewing. I suspect that there may be a good amount of resources in the ND archives.

Excellent, Evan! A great story I had never heard and well told indeed.

Thank you for the article regarding Rev. Bliemel, O.S.B., much of the information was new to me. If I disagreed with Fr. Emmeran’s politics, I can’t help but to admire his bravery and commitment. I wonder which side Fr. Emmeran would have chosen had he known then what we know now about the Confederate cause? Thank you for the article. Fr. Frank Ziemkiewicz, O.S.B., Savannah, GA

I certainly agree! Bliemel’s story certainly begs the question of why he sympathized so deeply with the Confederate cause, but the only existing account his motives are the testimony recorded by Truesdale that I cite in the article. Fascinating, for sure. Thank you for the comment!

Fascinating. Thank you for sharing.

thanks Evan … not much written about southern Catholics, let alone Confederate Catholic Chaplains … thank you for remembering Father Bliemel.

It would be more accurate to describe Fr. Bliemel’s activity in Nashville as “perceived treasonous business.” What would be considered treason in Union controlled areas would be considered as remarkably patriotic business in Confederate controlled cities.

Tom

Actually, Reverend Father Bliemel is interred at the Holy Cross Cemetery, Tuscumbia, Alabama.