Forts: “The Veritable Fort” — Fort McHenry & The Civil War

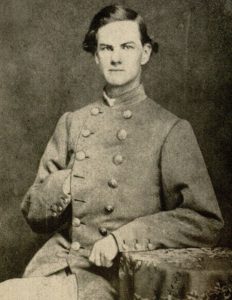

“At last we arrive at the veritable fort…” wrote Lieutenant John Dooley, recording his experiences on July 13, 1863.[i] Shot through both thighs ten days earlier at the Battle of Gettysburg, Dooley had been transported by his captors from The Angle to field hospitals and finally to Baltimore, Maryland. Hauled through the city’s streets in a jolting ambulance, he finally arrived with other wounded Confederate prisoners at the gates of Fort McHenry.

Construction on the fort had started in 1789 and frequent additions and strengthening made it a valuable defensive location for Baltimore, Maryland. Fort McHenry’s most famous military moment came in September 1814 when British ships bombarded the position during the War of 1812. The fort resisted the attack and “by dawn’s early light” the “Star Spangled Banner in triumphed waved”, inspiring a young lawyer named Francis Scott Key to write a patriotic poem, which later became the United State’s national anthem.

The fort’s commander during the 1814 attack — Major George Armistead — preserved the enormous flag that he had commissioned, and in 1907 some of his descendants loaned it to the Smithsonian Museum where it continues to be preserved today. George Armistead died in 1818, never seeing the sectional conflict that erupted into the Civil War in 1861. However, one of his nephew’s — Lewis Armistead — became a general in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, dying shortly after the Battle of Gettysburg where he led a brigade in “Pickett’s Charge.”

Fort McHenry’s Civil War history is less dramatic than its War of 1812 defense. The fort was dubbed one of the “American Bastilles” by a disgruntled Southern sympathizer who saw the interior more than he wished.[ii] Located near Baltimore, Fort McHenry was a convenient location to lock up Confederate military prisoners or civilians suspected of aiding the Confederacy. One of the political prisoners housed at Fort McHenry was Frank Key Howard, a grandson of Francis Scott Key.[iii]

The fort also acted as a military presence to help persuade Maryland to stay in the Union, particularly in 1861. The Baltimore Riot on April 19, 1861, established the city’s importance as a railroad hub and as a hotbed of Southern sympathies. A few months later, in July, General John A. Dix moved into Fort McHenry as the new commander of the Middle Department of the United States Military and started convincing the locals that rebellion would be useless. In one of his ploys, Dix hosted several prominent ladies of the city at the fort. As part of the “hospitable” entertainment, he escorted them to Baston 1 and carefully pointed out a cannon that aimed directed at Monument Square in their home city. Dix told the ladies, “If there should be another uprising in Baltimore, I shall be compelled to try to put it down; and that gun is the first I shall fire.”[iv] The ladies took the hint, but Fort McHenry’s cannons pointed two directions for the rest of the war: toward the harbor and toward the heart of the city.

Fort McHenry started holding political prisoners as early as 1861, but the majority of military prisoners came later — most after the Battles of Antietam and Gettysburg. The fort was a transition prison, and many captured Confederates passed through its gates for a short stay before they were sent to other POW camps or forts. Following the Battle of Gettysburg, 6,957 prisoners arrived and were held at one time.[v]

Among the thousands of prisoners arriving from Gettysburg came badly wounded Confederates, like John Dooley of the 1st Virginia Regiment. Suffering greatly from his wounds, Dooley had hoped to be taken to a hospital in Baltimore. Instead, “we who had fondly been picturing to ourselves a large hospital were dismayed to find our ambulances halt before a row of low buildings which appeared somewhat like those in which I have seen cattle quartered. Finally after much delay we are ushered up a filthy staircase into a filthy loft. We are huddled together in this noisesome place, filth and vermin in profusion. It is the uppermost story of the yankee guard house of the Yankee garrison quartered here. Col. Davis calls it the Black Hole of Calcutta.”[vi]

A few hours later “rations” were brought to the wounded in this upper loft. “A large iron bucket of greasy [word not decipherable] in slices and pan of crackers and hard tack.”[vii] The poor conditions made the prisoners rejoice at the news that they were heading to Fort Delaware prison the next day. However, that transfer didn’t happen, leaving them in the “black hole, Ft. McHenry.” To pass the time and try to keep up their spirits, “we moan during the day and sing at nightfall. It is a strange thing to see a lot of wounded, miserable, half-starved and melancholic wretches gathering in a social knot and forming a glee club to frighten off the more gloomy shadows of our prison walls. Imagination can do wonders in making one miserable or happy — ‘We’re saddest when we sing.’”[viii]

For days, Dooley did not record medical attention from his captors at Fort McHenry. Instead, a fellow prisoner tended to his wounds, removing maggots, extracting shredded cloth, and cleansing the injuries. Without a bed or proper cot, Dooley struggled to find a comfortable position to rest and the summer heat increased his pain. Two weeks after arriving at Fort McHenry, a post-surgeon walked through the room “to see if any of us are badly wounded enough to be taken to the hospital.”[ix] Dooley was carried to “the Post Hospital, a clean and quiet building but not adapted to the exigencies of war since it does not accommodate (I think) more than 40 patients.”[x]

At the hospital, Dooley was washed and stuffed into a bed “in the top story, with a tin roof slanting just over my head and the sun playing fiercely on its metallic covering.”[xi] Over the next days, the heat in the hospital raged into the upper 90’s according to the thermometer. Unsurprisingly, Dooley did not improve in these conditions. Separated from his comrades and fearing that he would become a “crisp” into the hot room, he became “wretchedly sick for several hours and nearly faint from excessive pain.”[xii] Finally, transferred to a better ward, Dooley started to feel better. The new wardmaster could be bribed to bring in “a pitcher of lager beer for which we pay 50 cents” and playing tricks on the strict wardmaster occupied the wounded Confederates’ waking hours.

On August 22, 1863, John Dooley left Fort McHenry, heading for a Johnson Island Prison. One among thousands who passed through the gates of the historic fort, Dooley had few fond memories of Fort McHenry.

The fort served its purpose through the Civil War years as a guarding influence and a prison. Its ramparts watched the harbor and warned the city’s inhabitants that open rebellion would be swiftly ended. In some ways, Fort McHenry had already had its moment of glory in the U.S. History saga, though it would have a significant medical role decades later in World War I. Its role in the 1860’s was far less exciting and inspiring of new poetry, but still the fort played its part in keeping Maryland in the Union and holding prisoners until parole or good behavior could be ensured.

Sources:

[i] John Dooley, edited by Joseph T. Durkin, John Dooley, Confederate Soldier: His War Journal, (Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame Press, 1963). Page 124.

[ii] Lawrence Sangston, The bastiles of the North, (1863). Access through archive.org.

[iii] “Fort McHenry & The Civil War” – NPS Article https://www.nps.gov/fomc/learn/historyculture/the-civil-war.htm#:~:text=Fort%20McHenry%20was%20never%20attacked,Pratt%20Street%20Riots%20were%20deterred.&text=A%20political%20massacre%20occurred%20in,were%20held%20in%20Fort%20McHenry.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] John Dooley, edited by Joseph T. Durkin, John Dooley, Confederate Soldier: His War Journal, (Notre Dame, University of Notre Dame Press, 1963). Page 124.

[vii] Ibid., Page 125.

[viii] Ibid., Page 126.

[ix] Ibid., Page 127.

[x] Ibid., Page 127.

[xi] Ibid., Page 128.

[xii] Ibid., Page 129.

1 Response to Forts: “The Veritable Fort” — Fort McHenry & The Civil War