The Lost 1890 Census and the Surviving “Special Schedule”

ECW welcomes back guest author Richard Heisler

Federal and state censuses are critical sources of data and useful information for historians and researchers working on topics related to Civil War veterans or their families. Census records, although imperfect, are among the most widely used and accurate sources for this type of work. Information contained in the census records aid in identifying and verifying names and locations of individuals and their families, occupations, birth years and locations and more. The Federal censuses of 1870 and 1880, as well as those from 1900 to 1930 are frequently consulted for these details during the veterans’ lifetimes. Conspicuously absent, however, is the 1890 Federal census. This void in information during a key period in the lives of Civil War veterans is unfortunate and frustrating. What is the reason that the 1890 census is unavailable?

The majority of the records from the 1890 census were damaged or destroyed in a Washington D.C. fire on January 10, 1921. The records were stored on open pine shelves in an unlocked file room in the basement of the Commerce Building. It was estimated that if the enormous collection of 1890 books were stacked side by side, they would extend for a distance of 1 ? miles. The storage of the priceless materials in such a manner in the basement of the Commerce Building had already been protested by many, to no avail. The records from the 1790-1830 and 1860-1870 census years were stored more securely on the 5th floor. Sadly, the worst-case scenario played out that evening when a fire broke out in the carpenter shop, also located in the building’s basement. The blaze quickly spread, resulting in a 5-alarm response to subdue the conflagration. An estimated 10,000 people gathered as spectators at the scene. To extinguish the flames firefighters cut holes through the first floor, seventeen in all, to get water on the burning materials in the basement. Approximately 25 percent of the 1890 census volumes were destroyed immediately in the flames and the majority of the surviving volumes were damaged beyond repair by water and smoke. Many volumes from the 1880, 1900 and 1910 censuses were also damaged but to a much lesser extent than the 1890 records.

The irreparably damaged volumes languished in storage for over a decade before the Census Bureau deemed them useless and ordered them to be destroyed. Despite protests from officials, historians, groups and organizations over that time, they were disposed of in 1934.

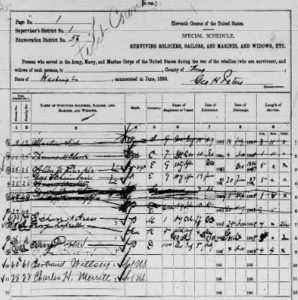

Not lost in the 1921 fire, however, were the records of a special schedule that accompanied the census. Officially known as the “Special Schedule – Surviving Soldiers, Sailors and Marines and Widows, etc.,” these records provided the names, location, service and other assorted details of former Union soldiers, sailors and widows in preparation for an expansion of Federal pensions for the former soldiers that had been approved by Congress. While not all of them have survived, those of most northern and western states have, making them a very important resource for researchers.

As rich in information as the censuses can be, it remains necessary to approach these records with an amount of caution. Issues with the documents can range from difficult to decipher handwriting and misspellings, to omissions and erroneous information. Most of these problems stem from the fact that census taking was a manual process and relied upon the individual enumerators performing the census for accuracy. The United States did not have an established census bureau to oversee the process directly until 1902. Prior to that time, enumerators were widely appointed by “political patronage” with no examination or qualifications required. Curiously, in 1890, unlike previous enumerations, the completed schedules were not even sent to county clerks for verification but were instead sent directly to Washington DC.

The process of taking the 1890 census was rife with fraud, intrigue and controversy. The effort was widely panned as a “lamentable failure.” Conflicts erupted around the nation over the census results. In Minneapolis and St. Paul violence flared over purported fraud. Cities such as San Francisco and Portland complained of problems. The fiercely competitive emerging cities of Seattle and Tacoma hurled insults and accused one another of inflating numbers. As both cities experienced enormous population growth in the 1880’s, with increases exceeding 1000%, the race was on to take top spot as the Puget Sound’s economic powerhouse. Despite their rivalry for position as the leading city on the Puget Sound, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reasoned, “If the enumeration is not satisfactory to the people of Seattle or of Tacoma, they can console themselves with the thought that their dissatisfaction is shared by the people of a hundred other cities. After all that has been said and done, the census apparently has been a farce.”

Problems with the census did not arise only from systemic issues, manipulation or fraud. In some instances, the failings originated with the enumerators themselves. Enumerator’s issues didn’t end in the form of bad handwriting or a misspelling. On occasion, it was just a fault with the actual enumerator and their ability to get the job done. The work of Seattle census taker George Peters illustrates just how difficult taking a reliable census in 1890 was. Mr. Peters’ handwriting was a mess and his veterans’ schedule page was chaotic. His census work was so bad that they had to be completely redone for his Duwamish district of the city. His responsibility was state district #56, which encompassed parts of modern-day Mercer Island, South Seattle and West Seattle. His enumeration of the district tallied a total of 1,120 people. For the special schedule he listed 11 veterans of the Civil War. Looking at his page of the veterans’ schedule, the disorder is obvious. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer explained why:

“George H. Peters, the enumerator of this district, was a very inefficient man and was only appointed because no better could be found. It is claimed that while he was supposed to be engaged at his work he lay at the White house for a week in a helpless state of intoxication and he was arrested and fined for vagrancy. He is, however, an old hand at the census business, having been an enumerator in 1880.”

Aware of the problems with Peters, a recount of the Duwamish district was ordered by census supervisor Thomas Prosch. Three men, George Gates, John Allen and George Wilkes received the assignment and came back with a total of 2,260 persons for district #56. The recount also extended to the Special Schedule of Veterans and many of Peters’ sloppy inaccuracies were corrected. His original tally of only 11 veterans swelled to a total of 42!

Despite the recount, interpreting some of what George Peters recorded is a challenge. Among the number tallied by Peters was a man he listed as Bertrand Willsey, only recorded as a “US Soldier” but was corrected by George Gates to name the proper individual, Lewis Willsey, who served in “Berdan’s Sharpshooters” Co I, 1st U.S.S.S. Likewise, Charles Merritt, recorded also as a “US Soldier” received proper identification as Charles Merrick, who served 3 years in the 8th Ohio Infantry. These are critical differences when attempting to accurately record the men’s histories. Some veterans that Peters lists are a total mystery, with names and regiments that do not seem to be found elsewhere. At one point, 3 names appear noted on corresponding but very unclear entries, one simply listing a Company K 3rd Michigan veteran that was “shot in the leg with a shell” and was “in bad shape.” The recount made no mention of a 3rd Michigan man in the district nor anyone who’d been wounded with a shell. The roster of Company K, 3rd Michigan Infantry does not appear to have any name resembling any one of the three that Peters listed. The specific identities and histories of these men remain elusive.

Peters’ work was not entirely without merit. He did add a unique detail describing one of the soldiers that was accurately identified in the initial and recount of the district. 7th Michigan Cavalry veteran Thomas Clark had suffered a wound to the left hand during the war, an important personal detail of his experience in the conflict. However, that information hardly compensates for the difficulty of trying to obtain useful information on these Seattle veterans from Peters’ botched attempt at enumerating the Duwamish district.

It was reported after the census work had concluded that George Peters was not likely to receive wages for the work of census taking and he was actually subject to a $500 fine for “failing to make a true and exact enumeration of all the residents of his district.” Along with his arrest and fine for vagrancy, this was not a good stretch of time for George Peters. His difficulties left a wrinkle in the historic record that has made the tedious work of untangling the histories of Seattle’s Civil War veterans that much more difficult. Working with the surviving census records can be as subtle and complex as the lives of the individuals they represent.

Richard Heisler is a 30 year resident of Seattle with a lifelong passionate interest in Civil War history. An early life steeped in history and art on the battlefields and in the museums of the Mid-Atlantic led to an education and career in art with history always being an underlying theme. Visits to the Gettysburg Cyclorama as a child were formative and helped set a life’s course with the paintbrush and the history book.

Richard is the founder of Seattle’s Civil War Legacy, a public history project aimed at bringing the rich and complex history of Seattle’s Civil War veterans to a broader, more diverse audience than would typically be exposed to this subject. Upwards of 3000 former Civil War soldiers and their families made their homes in Seattle and surrounding towns in the decades after the conflict. The legacy of these men during the Civil War and their subsequent roles in Seattle’s development are an underappreciated aspect of a shared national heritage. Seattle’s Civil War Legacy uses Social Media platforms, video, writing and tours all as part of the mission to bring Seattle’s Civil War connections to the public.

Sources –

“An Uncounted City” Seattle Post-Intelligencer July 13,1890 p.8

“The Census In Full” Seattle Post-Intelligencer July 14, 1890 p.1

“The Census Farce” Seattle Post-Intelligencer June 29,1890 p.4

“A Howl From Oregon” Seattle Post-Intelligencer August 7, 1890 p.9

“The Metropolis – Seattle’s Marvelous Development” Seattle Post-Intelligencer January 1,1890 p.8

“Fire Destroys Census Data of 120 Years” The Washington Herald, Washington D.C. January 11, 1921 p.1

“Fire Ruins Records” The Washington Post, Washington D.C. January 11, 1921 p.1.

United States Census 1890, Special Schedule – Surviving Soldiers, Sailors and Marines and Widows, etc.

“First in the Path of the Firemen” Genealogy Notes, Spring 1996, Volume 28, no 1.

Excellent insight – terrible loss for genealogists!

Fascinating article. My great, great grandfather’s Combined Service Records are mixed up with other soldiers of similar names (probably because my ancestor was illiterate) and are nearly indecipherable. I found the 1890 Special Schedule you mention key to proving that William Henry Sinclair served in the Third Maryland Volunteers Regiment at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg.

looking for my gr granfather Elijah Thomas of

Loo

Looking for gr. gr father Elijah Thomas from Tennessee in6 Civil War in6