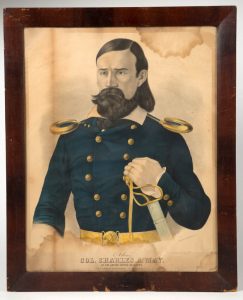

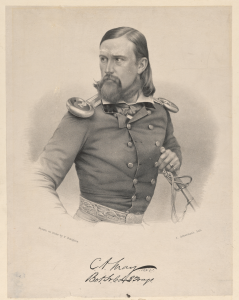

Exchanging a Saber for a Cane: The Case of Colonel Charles Augustus May

In 1861, over 250 U.S. Army officers resigned their commissions. The majority joined the rebellion, while a few remained loyal to the Union. Nineteen officers (seven percent) didn’t serve on either side. The choice was not so simple for these officers. Some were loyal to the Union but would not take up arms against friends who joined the rebellion, while others supported the Confederacy but refused to draw a sword against the Stars and Stripes or old army comrades. Others cited age or fragile health and choose to let younger men do the bloodletting.[1] Among the officers who elected to avoid fighting in the war, Brevet Colonel Charles Augustus May is the most celebrated.

Anybody who has studied the Mexican War is familiar with May. Thanks to American poets, songwriters, printer makers, and the press eulogizing the dragoon officer’s cavalry charge during one of the Mexican War’s first battles, May became a national celebrity almost overnight.[2] It only seemed natural that May would play a leading part in the American Civil War. Instead, he abruptly resigned his army commission and took a job with a New York City railroad company. When he unexpectedly died in 1864, both Northerners and Southerners mourned his loss. Mention of his name and exploits served as a remainder of better times. Americans had not forgotten the hero of Resaca de la Palma nearly 20 years later, despite civil war ravaging the country and the conflict heading into its fourth and final year.

The Gallant May

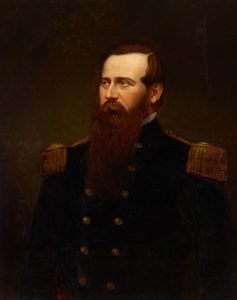

Few officers in Brigadier General Taylor’s army stationed along the Rio Grande attracted as much attention as May did. “You have seen the personal description of Captain May, given in a New Orleans paper — It scarcely comes up to the man,” a Baltimore correspondent wrote. “He is over six feet high; wears his hair long, so that it nearly reached his hips; his beard falls below his sword belt, and his mustache is unshorn.” The story goes that May refused to allow a barber to trim his hair or beard since he had his heart broken by a sweetheart years before.[3] “I remember a day or two after reporting for duty seeing a superb-looking horse, with arched neck and flowing mane, pass at a sweeping gallop,” Cadmus M. Wilcox recalled. “[H]is rider, tall and of soldierly bearing, with long hair and a beard, graceful and east in his seat, reigned up and dismounted at the headquarters of General Taylor.”[4] Another future Confederate general, James Longstreet, befriend the flamboyant cavalry officer and got to know him on a more personal level. “As a dragoon and soldier, May was splendid,” he recalled. “He was amiable of disposition, lovable and genial in character.”[5]

The Battle of Resaca de la Palma was May’s most glorious hour. Taylor ordered him to support First Lieutenant Randolph Ridgely’s guns taking heavy fire from an enemy battery. May and his squadron charged down the Point Isabel Road in columns of four and overran the battery and captured Mexican general Rómulo Díaz de la Vega and some others. But during the charge, his troopers became overextended and took heavy losses before returning to the American lines.[6]

While it was hardly the decisive moment in the battle, the American press sensationalized May’s charge. For instance, the Alexandria Gazette described May as being “in advance of them all, on his noble black steed, standing up in the stirrups, his head bent forward, his long hair streaming out behind like the tail of a comet and his appearance, viewed from the head, looking like one of those celestial visitants.” Some even compared him to the legendary French knight Bayard.[7] But his exploits were grossly exaggerated by the press. “The story of his charge against the Mexican guns grew as it was repeated until its details became lost in fantasy,” historian Robert W. Johannsen explained. “No one questioned that it was one of the most heroic exploits ever recorded in history.”[8]

The Bold Dragoon

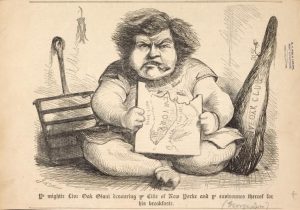

While there were no dashing cavalry charges for May during the interwar period, he still found a way to get his name in the papers for other reasons. Most notably was his lavish wedding. While he was said to have been “crossed in love” (at least as the story goes), he eventually found love again.[9] On February 8, 1853, May married 19-year-old Josephine Law, the daughter of the steamboat proprietor, millionaire, and Know-Nothing Party presidential candidate, George Law.[10] They were married at New York City’s Old South Dutch Reformed Church at Fifth Avenue and 21st Street. “The bride was arrayed in a splendid white satin dress, covered with rich Mechlin lace, the cost of which, independent of jewels, was $1,500,” a New York correspondent of the Albany Express reported. After the ceremony, 400 people attended the reception at Law’s mansion. “The supper tables were laden with the choicest game, the finest wines, and all the delicacies which the imagination could conjecture,” the reporter continued. “The company comprised the wealthiest and most respectable of our citizens, and the display of beauty and of riches would seem incredible.”[11] Another paper joked that the lavish expenditure “afforded the young girls, widows and old maids themes for gossip for fully seventeen days and a half, after which is probable the affair will die away and be forgotten.”[12]

Even though marrying into wealth, May remained with the Dragoons. He took charge of the Cavalry School for Practice at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, which later relocated to Carlisle, Pennsylvania. After graduating from West Point, Second Lieutenant William W. Averell reported to the school and was impressed with its superintendent. “We had all heard of Colonel May as the dashing dragoon who had led the charge of Resaca in the Mexican war, capturing General La Vega and a battery of artillery,” Averell recalled. “We found him a tall, graceful man, about six feet four, with a long flowing beard of dark brown color and neatly trimmed, ample hair, a striking well-bred face capable of varied expressions and keen grey eyes which with his quick eyebrows made one suspect at first view that he was an emotional man and quick to anger — perhaps with a temper a trifle dangerous.” That evening the young officers called on Mrs. May to pay their respects. “Mrs. May … was an ideal wife for a commanding officer,” Averell continued. “Hospitable, always in perfect health with a sunny, sympathetic nature and lovely manners, she could make her home an oasis in any desert of a garrison.”[13]

Josephine May likely helped to counter her husband’s eccentric personality but she could not tame the streak of wildness and dash he still had in him from his youth and that carried him through the Mexican War. One of his favorite songs was The Bold Dragoons, which celebrated the romantic life of a dragoon. He personified everything that a dragoon embodied, not just in appearance. Not surprisingly given his quick temper, he was an authority on dueling and a crack shot with a pistol. Averell recalled that Captain (future Confederate Brigadier General) James McIntosh “had a temper as hot and quick as Colonel May’s,” and two headstrong men butt heads on one occasion. After placing McIntosh under arrest due to a trivial oversight in his duties, it took Averell two or three days to reason with the two men to avert a potential collision.[14] Even with some notable flaws, May left an overall favorable impression on Averell, and he was said to be popular among his officers and the men under his command. He undoubtedly left an impression on the other young officers under his tutelage who would also go on to serve in senior roles during the American Civil War.[15]

Premature Retirement

After a 33-hour cannonade, the Union garrison at Fort Sumpter surrendered. Seven days later, Brevet Colonel Charles A. May abruptly resigned his army commission. He was among the most senior ranking U.S. Army officers to leave the service. Washington, D.C.’s Evening Star listed his name only third behind Joseph E. Johnston and Robert E. Lee as the most notable officers to resign.[16] May quietly headed to New York City and took one of the last positions that seemed appropriate for a veteran dragoon: He became superintendent of the Eighth Avenue Railroad Co., a company owned by his father-in-law. It seems strange to picture a towering 6-foot, 4-inch ex-dragoon officer roaming the bustling streets of New York City wearing a suit and carrying a cane instead of the frontier plains wearing a dusty frock coat and carrying a saber.

May could have easily secured a senior position due to the fame he gained at Resaca, experience as a cavalry officer, and senior rank in the Regular Army. What could have been his motives for resigning and slipping into obscurity? May’s family background might provide some clues.[17] Dr. John Frederick May, a brother, successfully identified John Wilkes Booth’s body by a scar that he had made on the back of the assassin’s neck after removing a tumor.[18] A sister, Laura, married George D. Wise, who was brevetted a brigadier general at the end of the war. However, another brother, Henry May, a U.S. Representative from Maryland, was arrested for disloyalty in Baltimore in September 1861.[19]

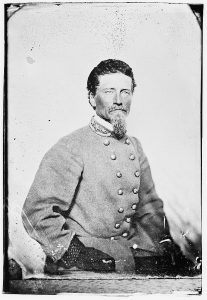

First Lieutenant Dabney H. Maury befriended Charles A. May before the war and participated in his brother Julian’s funeral. The Confederate general hinted that he leaned toward the southern cause. “While his sympathies were with his own people in the South,” he wrote, “he could not array himself against the people of his wife, who was a very admirable lady, to whom he was much attached.”[20] We will never know for sure if Maury’s statement is true. May did not leave behind any correspondence, journal, or memoir to shed light on this claim, but it is not a stretch to suppose he avoided a rift with his wife’s family. Instead of taking up arms against the south, he chose not to fight at all.

More than one newspaper reported that during the summer of 1861 a man called on Governor Edwin D. Morgan at Albany, New York, with a desire to meet Jefferson Davis in person — and he was not referring to a friendly afternoon over tea. Before offering him a commission, the governor asked the man if he knew anything of tactics. “Well, a little,” the man replied. “[I] think I could lead a company — just as soon go in the ranks.” Morgan then asked who he was. “May — Col. May. You may remember me,” he allegedly stated. “If Col. May, late of the United States dragoons — the man who resigned because he was maltreated by Jefferson Davis when the latter was Secretary of War — gets at the head of a regiment,” he said, “we may see tremendous feats of Palo Alto reenacted.”[21] Morgan (or the newspaper reporter) mixed up the Battle of Resaca de la Palma with the Battle of Palo Alto. But the had his point. Perhaps May made a detour before heading to New York City, but while it makes for a good story, the colorful exchange between Morgan and May probably never took place. If May did seek a volunteer commission, he never received it.[22]

The papers did not mention May’s name until 1864. On May 18, 1864, The New York Herald reported drivers of the Eighth Avenue Railroad Co. gathered at the corner of Ninth Avenue and Fiftieth Street where they “unanimously resolved that we do return our sincere and earnest thanks” to Superintendent Charles A. May and Deputy Superintendent Herman B. Wilson “for the prompt and generous compliance with our recent request for the reduction of the number of our working hours from fourteen and one-half to twelve hours per day.”[23] Besides advocating for lowering the company’s working hours, May removed the racial barriers for African Americans traveling in the railroad’s car. On July 2, 1864, the Alexandria Gazette said, “Col. Charles A. May, superintendent of the Eighth Avenue Railroad, in New York, notifies the public that ‘hereafter colored people will be allowed to ride in all the cars of the company, both great and small’ — there being no longer ‘colored cars.’” This could have been a clue to reveal May’s views toward slavery and African American rights, and perhaps another reason why did not join his friend Maury and others in the rebellion.[24]

Neither Side Could Claim His Fame

While some papers rebuked officers who chose to sit out the war, May seemed to be untouchable.[25] The press did not censure him for failing to pick a side or participate in the conflict. Maury probably came closest to expressing any enmity for May not taking up arms for the Confederacy, but it can hardly be viewed as anything close to hostility. Instead, he attributed it to his wife’s family. Helen Longstreet mentions May in Lee and Longstreet at High Tide, where she simply glosses over her husband’s friend by stating that “He took no part in the Civil War.”[26]

When he unexpectedly died of heart disease at the age of 46 on December 24, 1864, both Northern and Southern papers eulogized May.[27] His death took place the same month as Thomas’ victory at Nashville, the assault and capture of Fort Fisher, and Sherman’s march on Savannah, but the papers still found the space to mention his untimely death. His charge at Resaca, which had captured the American imagination over a decade before, had not been forgotten. Newspapers in Virginia and North Carolina shared his obituary originally published by the New York Times. Neither mentioned his abrupt resignation and relocation to New York City.[28] Rather, all of the columns focused on a life tragically cut short.[29]

Some Northerners and Southerners viewed the Mexican War as a better time when Americans fought together for one common cause, instead of against each other. “[O]n the rolls of that noble army of the Union, enlisted for all time, the company of patriot soldiers who, fighting together side by side under the one flag of their fathers, knew no North, no South, no East, no West,” the Wilmington Journal declared in January 1865. May had won for all Americans a “common triumph” and a “common fame” during the war with Mexico. The newspaper went on to criticize his comrades who were now fighting in a war that ravaged the country. “Others, his companions in arms, during that glorious episode of our annuals, have since made themselves more widely known in the conflicts of the civil strife which now desolates the republic,” the paper complained. But it praised the dragoon officer for refusing to do the same, and claimed that “the fame of May neither South nor North can claim.”[30] Charles Augustus May remained a hero to all Americans, and no war, even a civil war, could take that away from them.

Endnotes

[1] In 1861, 269 U.S. Army officers resigned. Nineteen did not participate in the war: Thomas T. Fauntleroy, Henry J. Wilson, Matthew Mountjoy Payne, William H. Bell, Alfred Mordecai, Charles A. May, George G. Waggaman, Joseph Selden, James B.S. Alexander, Rodney Glisan, Aquila T. Ridgley, Robert B. Reynolds, George C. Hutter, Richard Fatherly, Crawford Fletcher, John Trevitt, Henry B. Schroeder, Francis T. Bryan, and John C. Bonnycastle. Official Army Register for 1861 (Washington, D.C.: Adjutant General’s Office, 1861), 72-76. Both Fauntleroy and Selden considered Confederate commissions but were never appointed. “Document No. 32. Report of the Committee on Confederate Relations, Relative to Officers Resigning Out of the U.S. Service, and Entering the Service of Virginia, & c., & c., & c.” in Message of the Governor of Virginia, and Accompanying Documents (Richmond: William F. Ritchie, Public Printer, 1863), 5-6.

[2] Robert Johanssen, To the Halls of the Montezumas: The Mexican War in the American Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 128.

[3] “Captain May,” Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, VA), June 12, 1846.

[4] Cadmus M. Wilcox, History of the Mexican War, ed. Mary Rachel Wilcox (Washington, D.C.: The Church News Publishing Co., 1892),

[5] James Longstreet, From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America (Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott Co., 1896), 28; Helen D. Longstreet, Lee and Longstreet at High Tide: Gettysburg in the Light of the Official Records (Gainesville, GA: Published by the Author, 1905), 149.

[6] John S. D. Eisenhower, So Far From God: The U.S. War with Mexico, 1846-1848 (New York: Random House, 1989), 83; K. Jack Bauer, The Mexican War 1846-1848 (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1974), 60-62. Some claimed May had more brawn than brains. Samuel Chamberlain described him as an “Ass in the lion’s skin.” But Victorians loved their charges. Johanssen, To the Halls of the Montezumas, 129; Abner Doubleday, My Life in the Old Army: The Reminiscences of Abner Doubleday from the Collections of the New York Historical Society, ed. Joseph E. Chance (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1998), 305.

[7] “Captain May,” Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, VA), June 12, 1846.

[8] Johanssen, To the Halls of the Montezumas, 127-28.

[9] Ellan Swan, the daughter of Baltimore attorney James Swan, may have been the woman that broke May’s heart. While discussing Daniel Sickles’ murder of Philip Barton Key II, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper stated, “Mr. Key, at about the time of his marriage, narrowly escaped a duel with Colonel May, who had been a suitor to Miss Swan.” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (New York, NY), March 12, 1859. Ellan Swan married Philip Barton Key II on November 18, 1845, on the eve of the war with Mexico. She died in Washington, D.C. on March 20, 1855. Sickles shot and killed Key after discovering he was having an affair with his wife. American and Commercial Daily Advertiser (Baltimore, MD) November 20, 1845; “Deaths,” Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.), March 22, 1855.

[10] Yazoo Democrat (Yazoo City, MS), March 9, 1853; Connecticut Courant (Hartford, CT), February 19, 1853; “How One Man Got Right,” Cleveland Leader (Cleveland, OH), November 26, 1881. Law left behind large inheritance estimated to be between 2 million and 6 million dollars when he died on November 18, 1881. “George Law’s Will,” New York Herald (New York, NY), November 26, 1881.

[11] “The Marriage of Col. May,” Arkansas Whig (Little Rock, AR), March 10, 1853.

[12] Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA), February 25, 1853.

[13] William W. Averell, Ten Years in the Saddle: The Memoir of William Woods Averell, 1851-1862, ed. by Edward K. Eckert and Nicholas J. Amato (San Rafael, CA: Presidio Press, 1978), 55, 57.

[14] Averell, Ten Years in the Saddle, 65-69.

[15] “Departure of Troops,” Bedford Gazette (Bedford, PA), June 13, 1856.

[16] “Army Officers Resigned,” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), April 23, 1861. Of the 19 officers who resigned that ranked May, 12 became Confederate generals and one a lieutenant colonel. Another became a Union general. The remaining five, May included, chose not to serve. Official Army Register for 1861, 72-76.

[17] A brother, Commander William May of the U.S. Navy, died in October 1861. “Death of Commander May, U.S. Navy,” Sun (Baltimore, MD), October 12, 1861; Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.), October 25, 1861. Another brother, First Lieutenant Julian S. May, died of apoplexy in Tecolote, New Mexico, in 1859. Penny Press (Cincinnati, OH), January 5, 1860; Leo E. Oliva, Fort Union and the Frontier Army in the Southwest (Santa Fe, NX: National Park Service, 1993), 609. Maury was fond of the Mays. “They were a gallant race, those Mays, he stated. “[T]he men handsome and proud, and the women beautiful.” Dabney H. Maury, Recollections of a Virginian in the Mexican, Indian, and Civil Wars (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1894), 106-107.

[18] Allen D. Spiegel, “Dr. John Frederick May and the Identification of John Wilkes Booth’s Body,” Journal of Community Health 23, no. 5 (October 1998): 383-405; William H. Dennis, “Biographical Sketch of John Frederick May, M.D.,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 13 (1910): 49-51.

[19] “A Blow at Baltimore Rebels,” New York Tribune (New York, NY), September 14, 1861. May was later released in early October and able to attend his brother’s funeral. “Death of Commander May, U.S. Navy,” Sun (Baltimore, MD), October 12, 1861.

[20] Maury, Recollections of a Virginian, 107. On April 25, 1861, George Law wrote to Lincoln urging him to take action to crush the rioter in Baltimore in order “to sustain the government and maintain the Union.” Law was criticized for writing such a strongly worded letter to Lincoln. The New Hampshire Sentinel even called him the self-educated lieutenant-general of the armies of America.” “Gorge Law to President Lincoln,” The World (New York, NY), April 26, 1861; “The Administration Vigorous,” New Hampshire Sentinel (Keene, NH), May 2, 1861.

[21] “A Customer for Jefferson Davis,” Wood County Reporter (Grand Rapids, WI), June 1, 1861. The author did not find evidence of preexisting animosity between Jefferson Davis and Charles A. May.

[22] The Evening Star reported that May “had been on three months’ leave of absence, and on ascertaining the position of things here, hastened back, and has reported himself at the War Department for duty.” Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), April 20, 1861. May resigned from the U.S. Army on the same day the newspaper reported that he arrived in Washington to report for duty.

[23] The New York Herald (New York, NY), May 18, 1864.

[24] Alexandria Gazette (Alexandria, D.C.), July 2, 1864.

[25] In September 1861, the Richmond Examiner stated, “Major Alfred Mordecai of North Carolina, late of the United State army, has not yet joined our cause as reported. He has quietly settled in Philadelphia, and takes pains to publish his ‘loyalty’ in the Northern papers.” Richmond Examiner (Richmond, VA), September 24, 1861.

[26] Longstreet, Lee and Longstreet at High Tide, 149.

[27] According to the cemetery records, May was interred at New York Marble Cemetery on December 26, 1864, two days after his death at the New-York Hotel. His remains were removed in March 1865 and reinterred at Green-Wood Cemetery. Email correspondence with Ian H. Fraser, Board President, New York Marble Cemetery, February 14, 2022; Email correspondence with Anne W. Brown, Trustee, Em., NYMC, January 29, 2022. May is buried in the same lot as his wife. Email correspondence with Jeff Richman, Cemetery Historian, January 31, 2022.

[28] “Death of Colonel Charles A. May,” The Daily Dispatch (Richmond, VA) December 31, 1864; “Death of Col. Charles A. May,” Wilmington Journal (Wilmington, NC), January 12, 1865; Semi-Weekly Standard (Raleigh, NC), January 27, 1865.

[29] “But an organic tendency to disease of the heart, to which his brother, Captain Julian May, some years since succumbed, developed itself into sudden and fatal force, and aggravated probably by his increased devotion to the duties of his position among us, into which he carried a military thoroughness and exactness of administration, over-matched even his colossal strength of frame.” “Colonel May,” The Evening Telegraph (Philadelphia, PA), December 27, 1864. “Only forty six years of age, his stalwart frame and untiring activity seemed to promise many great years of useful life, but a heart disease, of which his brother Julian died, and toward which he had a constitutional tendency, terminated his career in the very vigor and prime of manhood.” “Death of Colonel May,” The Cecil Whig (Elkton, MD), January 7, 1865.

[30] “Death of Col. Charles A. May,” Wilmington Journal (Wilmington, NC), January 12, 1865.

James B. S. Alexander did join the Confederates as a captain. I haven’t found much information about him, but his obituary states that he was sent to Laurel Hill as an aide(?) to Gen. Garnett. He succumbed to illness after spending several days helping the army retreat through the mountains.