America’s First Air Force: Union Aeronauts and McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign Part Two – A Novel Contraption

ECW welcomes back guest author Jeff Ballard

With the bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, “numerous balloon enthusiasts hurried to Washington D.C. and besieged the War Department with various proposals for achieving victory by use of the air.”[1] Wise was present, as were John Allen with two balloons and Lowe with his two balloons. Wise received a tryout at First Bull Run (July 18, 1861), which proved a dismal failure. Wise was unceremoniously sacked after mismanaging balloons, “constructed at great expense to the U.S. Government causing their destruction.”[2] Lowe was next in line. Being well known to President Lincoln, for having already made a series of successful ascents, gave him a leg up.[3] Lowe also had the backing of Joseph Henry, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.

As frightened spectators and routed Union soldiers streamed back to Washington after Bull Run, Lowe sent a telegraph to the War Department from the gondola of his balloon 500 feet above the capital. His soothing message to President Lincoln, the first wartime air-to-ground communication ever recorded in America, was, “The city with its girdle of encampments and impregnable defenses, presents a superb scene…”[4]

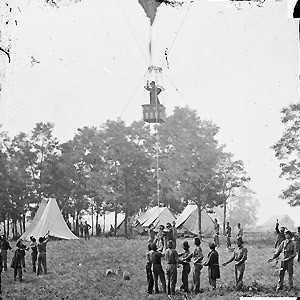

Lincoln nudged General Winfield Scott, Commanding General of the U.S. Army, and Lowe’s “novel contraption” was soon accepted as the new tool of the U.S. Army’s 1st Balloon Corps. Thaddeus Lowe was named the Chief Aeronaut for the U.S. Army.[5] From October 1861 to early 1862, Lowe dispersed his balloons along the Potomac River to give Washington some degree of security.

Lowe secured government funding for the construction of five additional balloons, and twelve wheeled field gas generators. He also built a flat-topped barge by removing the superstructure and engines from the old steamer, George Washington Parke-Custis making it the world’s first aircraft carrier.[6] Balloons were rarely deflated to save valuable gas. Instead, to shift a balloon’s base of operations rapidly, the fully inflated balloon would be pulled overland by the ground crews or towed by a steamship up or down a river.

While deployed near Richmond, a special “telegraph train” accompanied the Balloon Corps. This mobile telegraph station consisted of a telegraph key, a heavy 150-volt lead-acid electrical storage battery, and a large spool with 5-miles of insulated wire, all mounted on a horse-drawn wagon.[7]

Approximately thirty men were required to transport the equipment, establish a balloon station, and inflate the balloons. Prior to April 16, 1862, a detail of thirty men from the 4th Maine accompanying Lowe established a station at Gaines’ Farm. After the 16th, thirty-five men from Company A, 85th Pennsylvania manned the station, until it was abandoned on June 28th. Similarly, a detail from the 20th Massachusetts provided ground support for the Mechanicsville Station. Ground crews could inflate the largest balloons in a little more than three hours.[8]

While operating near Washington D.C., Lowe drew on the public gasworks to inflate the balloons, but field operations required the development of mobile, self-contained, gas generation capability. For this purpose, Lowe invented mobile gas generators built on a standard army-issued wagon. The generators used a copper-lined vessel, eleven feet long by five feet tall and five feet wide, in which 800-pounds of iron filings were soaked in forty gallons of sulfuric acid. A solution of water and lime twice purified the expanding gas before it was pumped by a rubber hose into the valve at a balloon’s base. The balloons, special wagons, sulfuric acid, ropes, valves, hoses, and other spare parts made military aeronautics a very expensive venture but, “the Balloon Corps was rarely denied its supplies, especially in the early stages of the war.”[9]

Gunfire was a threat to Lowe’s balloons. However, despite their best efforts, Rebel artillerymen scored no hits. Confederate gun crews often elevated cannon above their safe incline in a vain attempt to hit a balloon, only to have the shell explode in the barrel and destroy the gun.[10] Often high winds, trees, and shrubs threatened the flimsy balloon silk. Ground crews used heavy brooms to sweep the station free of debris before laying out canvas from captured tents to inflate the balloons upon. Forty-gallon glass carboys of sulfuric acid and the ever-present highly flammable hydrogen gas were always a concern. While accidents undoubtedly occurred, no fatalities or loss of equipment were recorded.

Three of Lowe’s seven balloons participated in the battle at Fair Oaks. The Intrepid, the largest balloon used during the Civil War, was stationed at Gaines’ Farm. With a 32,000 cubic foot capacity, it could carry five men aloft in its red, white, and blue, bunting-covered basket. A large portrait of McClellan, suspended from the beak of an eagle, adorned one side of Intrepid’s envelope. The Constitution, stationed at Mechanicsville, could accommodate three men with its 25,000 cubic foot capacity. The one-man Excelsior was the smallest of the three, but its 15,000 cubic foot capacity envelope could be inflated in much less time than the others.[11] Once inflated the balloons would remain buoyant for a fortnight and the gas could be transferred between balloons to save the precious hydrogen.

The Confederates also fielded a balloon. It was officially named Gazelle but referred to as “Lady Davis” or the “Silk Dress Balloon” by Union troops because the silk used in its construction was taken from bolts of various dress patterned material.[12] Buoyed by hot air, rather than hydrogen gas, it could not ascend above 500 ft.[13] The Gazelle also observed the action at Fair Oaks from its position southeast of Richmond and was easily visible to Lowe. The Gazelle was destroyed on July 4, 1862, when a Union gunboat captured the armed tugboat which was transporting the balloon and its crew down the James River.[14] After the loss of Gazelle, the Confederates never launched another balloon over the battlefield.

All that remained was for Lowe and his balloons to prove themselves in battle and in a very significant way justify their weighty cost. They would not have long to wait.

Jeff Ballard is a historian, writer, and the Editor-in-Chief of The Saber and Scroll Journal. He has written numerous magazine and journal articles on topics in military history, American political geography, and social history. He earned his master’s degree in Military History, with Honors, from American Military University in 2015. Jeff’s thesis and the bulk of his subsequent research and writing focus on shifts in US Navy tactics and doctrine during the Guadalcanal Campaign 1942-1943. This native Californian lives in Huntington Beach with his wife Carol, son Andrew, and Chihuahua/Min-Pin mix Taco Bell.

[1] Duane J. Squires, “Aeronautics in the Civil War” The American Historical Review 42, no. 4 (Jul., 1937), 652-669. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1839448 [accessed: April 17, 2022], 657.

[2] Dr. James L. Green, “Civil War Ballooning During the Seven Days Campaign” Civil War Trust. http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/civil-war-ballooning/ballooning-during-the-seven.html [accessed: July 15, 2013].

[3] Squires, 658.

[4] Allan W. Howey, “War of the Aeronauts: The History of Ballooning in the Civil War,” Air & Space Power Journal 17. no. 3 (Fall 2003): 121.

[5] Ibid., 122.

[6] Green.

[7] Evans, 166.

[8] Ibid., 122.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Green.

[11] Evans, 122.

[12] Green.

[13] Joseph P. Cullen, The Peninsula Campaign 1862: McClellan & Lee Struggle for Richmond (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1973), 194.

[14] Ibid., 54.

1 Response to America’s First Air Force: Union Aeronauts and McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign Part Two – A Novel Contraption