From Chicory to Cigar Stumps: Confederate Coffee Alternatives in the Civil War

In just about any firsthand account of the Civil War, it’s striking how heavily coffee features in the day to day lives of soldiers. Like many of us today, both Union and Confederate troops found coffee to be absolutely essential as a stimulant, a source of warmth and comfort, and a ritual to congregate around.

In his aptly titled account of a Civil War soldier’s day to day life, Hardtack and Coffee, John Billings of Massachusetts noted that “It was coffee at meals and between meals; and men going on guard or coming off guard drank it at all hours of the night.”1

Confederate Private Carlton McCarthy of the Richmond Howitzers waxed somewhat more poetic in describing the allure of coffee: “What is that faint aroma which steals about on the night air? Is it a celestial breeze? No! it is the mist of the coffee boiler.”2

The soldier’s profound dedication to coffee was hardly limited to the rank and file. After losing the battle of Valverde in 1862, Union Colonel R.S. Canby was in the difficult position of having the Confederate Army of New Mexico in a central position between himself at Fort Craig, and the remainder of his department’s troops and his lines of supply and communication via Fort Union and up into Colorado.

Trying to coordinate his efforts with subordinates at Fort Union, Canby wrote to Col. John Slough of the 1st Colorado, urging him to move quickly and with minimal baggage across the hostile terrain of northern New Mexico. What bare essentials did Canby consider to be necessary rations in such an emergency? Only “bread and meat, coffee and sugar.” Moreover, he took the time to instruct Slough to, “Increase the coffee and sugar for guards and pickets.”3

As the Confederacy would soon learn, considering something essential doesn’t mean that it will be available.

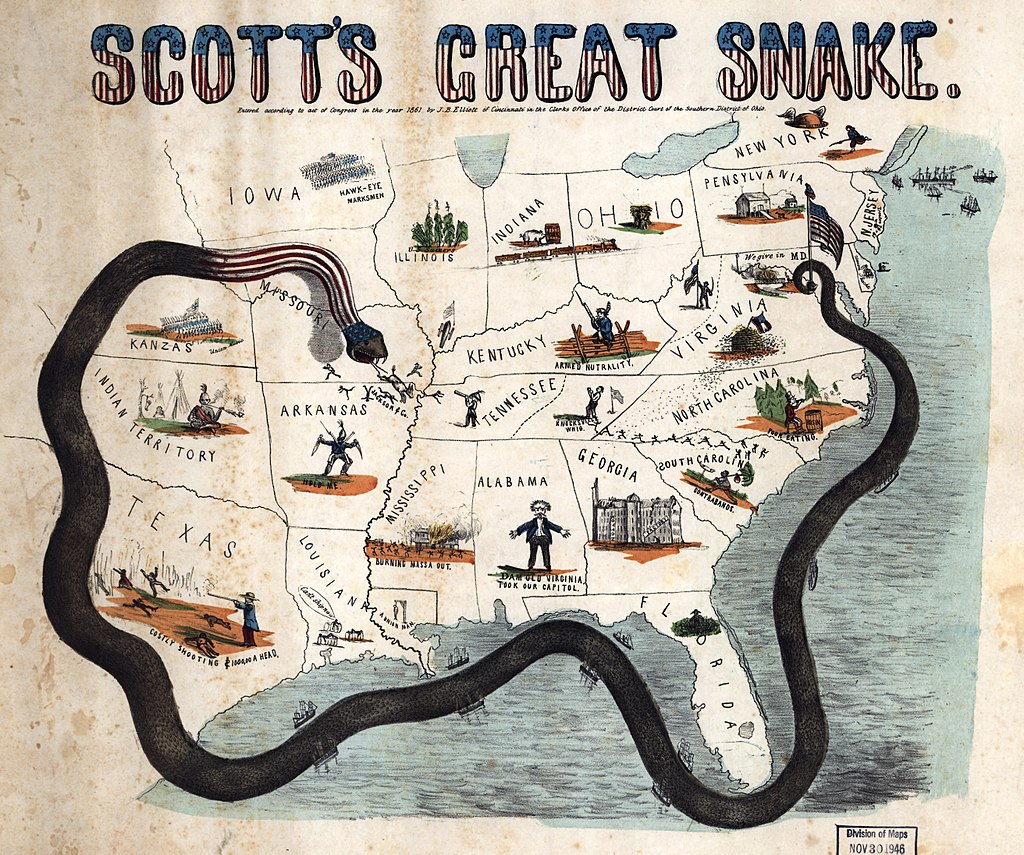

At the outset of the war, the states of the Confederacy were largely dependent on outside commerce for weapons, manufactured goods, and certain commodities…including coffee. At the heart of the Union war strategy was an effort to blockade the seceded states, cutting them off from the outside trade they would need to keep the war effort going.

The Union blockade quickly took its toll on Southern coffee drinkers. In late May, the USS Brooklyn sent a message to Fort Jackson, guarding the approach to New Orleans, announcing that they had arrived at the mouth of the Mississippi River to enforce the blockade. On May 30, the first ship seized on its way to the Confederacy’s largest city was the H.E. Spearing, carrying $120,000 of Brazilian coffee.4

As the war progressed, the blockade grew steadily more effective as the Union deployed more ships and captured vital Confederate ports. The Confederate economy began to collapse, and it became harder and harder to acquire any number of items: ammunition and weapons for the army, medicine, even food. While their cargo manifests frequently include smuggled coffee, blockade runners could only make a dent in the shortages.5

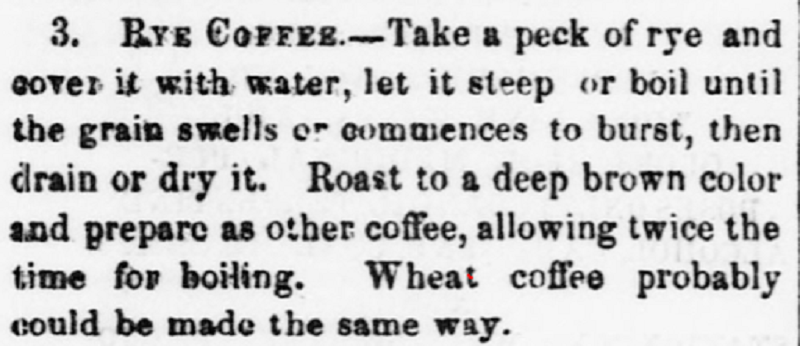

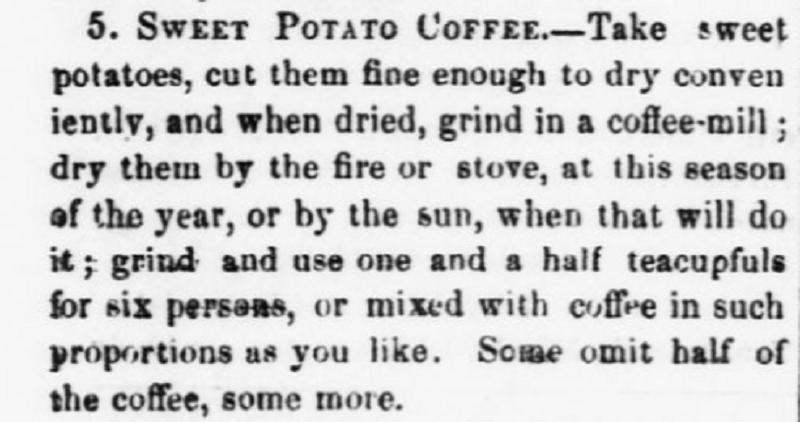

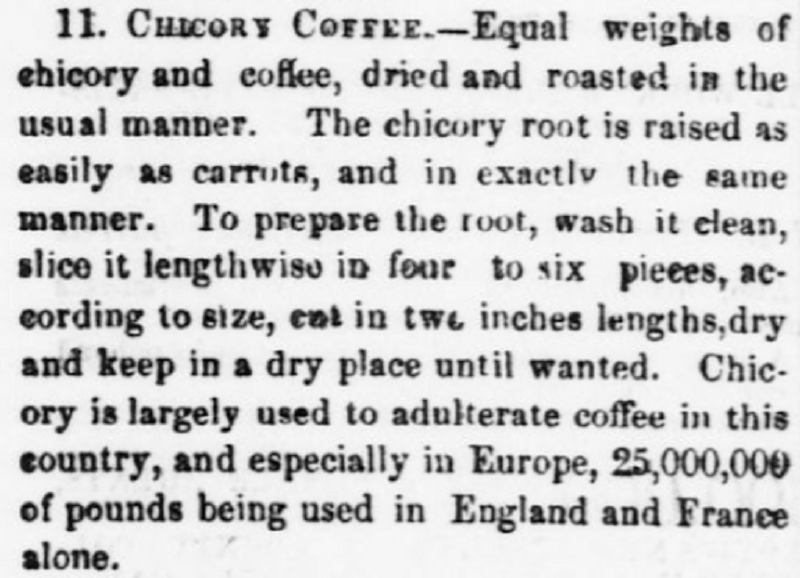

So what do you do when you’re expected to live outside and fight a war – or you’re struggling on the homefront – and you can’t get your coffee fix? Necessity is the mother of invention, and across the Confederacy, civilians and soldiers alike came up with a fascinating range of substitutes: roasting any number of grains or plants that could be grown domestically, including okra, rye and sweet potatoes; using other ingredients to stretch what coffee was left; even a ubiquitous weed called “wild coffee” that was conveniently found in New Orleans.6

Inspired by these descriptions of New Orleans substitutes, and Ashley Webb’s and Sarah Kay Bierle’s past articles on the topic, I decided to try some of these for myself. A survey of coffee alternatives in Confederate newspapers turns up a staggering number of options, but sweet potato, rye and chicory stood out as some of the most commonly mentioned substitutes that would still be reasonably available today.7

First up was the rye. On the one hand, it’s safe to assume that your average Civil War soldier had considerably more experience than I do when it comes to cooking over a campfire. I’m not confident that I got the rye as roasted as you would want for a full coffee flavor, so this might be worth trying again. But on the other hand, in the words of my (extremely tolerant) wife, this just tasted like “warm grainy water.”

The sweet potato substitute was actually pretty good. As long as we’re grading on a curve, it had a surprisingly full body and rich flavor, and was reasonably easy to prepare. Sweet potatoes would also have been readily available as a substitute in the South. As of the 1860 census, states that seceded grew 90% of the country’s crop.8

I’m not going to give up my morning pot of coffee in favor of sweet potatoes any time soon, but I could actually imagine this filling some of the void left by blockaded coffee if you found yourself out on a picket line on a winter night. That said, the preparation didn’t look particularly appetizing, unless you want a bright, chunky, orange drink for breakfast. You’ll want to pour this one pretty carefully to avoid getting too much of the “grounds,” and maybe don’t look too closely at it.

Finally, we tried the chicory, split 50/50 with real coffee. Given that there was some real coffee involved, it’s not surprising that this was the most appetizing – and of course, that only works as a way to stretch existing coffee, rather than being a true substitute. This drink is still popular in some places, and it’s easy to understand why it would have been appealing at the time.

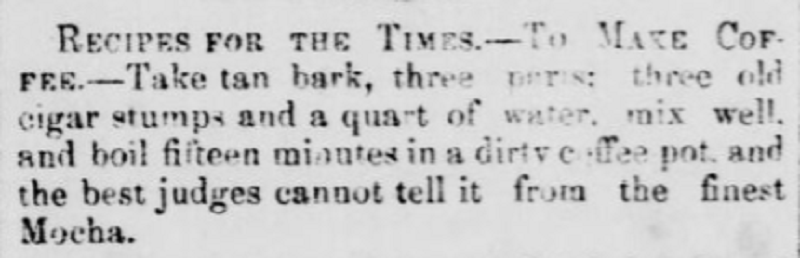

In closing, I have to confess that I wasn’t brave enough to try this alternative involving boiled cigar stumps, which I can only hope was tongue-in-cheek. If anyone tries this, be sure to tell me how it was!

1. Billings, John D. Hardtack and Coffee. Enhanced Media Publishing, 2017, 67.

2. McCarthy, Carlton. Detailed Minutiae of Soldier Life in the Army of Northern Virginia, 1861-1865. Nebraska Press. 1997, 75.

3. United States. War Records Office, et al.. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union And Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume IX, Chapter XXI. 1880, 649.

4. Dufour, Charles. The Night the War Was Lost. Bison, 1994, 42.

5. Cargo Manifests of Confederate Blockade Runners. NCPedia. Accessed August 23, 2022.

6. Dufour, 62.

7. Betts, Vicki, “Coffee and Coffee Substitutes in the Confederacy” (2016). Special Topics. Paper

8. “Agriculture of the United States in 1860”, Washington Government Printing Office, 1864, xxxi.

As I mentioned in an earlier comment, my grandmother sang a song she had learned from her grandmother, widow of an Alabama Confederate officer, that began, “Old Jeff Davis is a-getting mighty grand/setting down to dinner with a coffee pot of bran . . .” I haven’t tried it, but apparently that was another popular coffee substitute.

The small (sic) travails of women during the War bear exploring, too. Another story from my grandmother illustrates this. When her grandfather was away “fighting with Gen. Lee up in Virginia,” he wrote home that he needed a new uniform, and her grandmother and friends set out to make him one. I imagine that under the circumstances at the time, that may have even involved carding the wool and cotton needed to spin and make the cloth (I still have her carding boards). When it was finished, they dutifully sent it off to him, only to receive a letter in return that his tent had taken a direct hit from a cannon shot, which destroyed the uniform after one wearing, so could they please make him another. The women’s war was quite different from the men’s, but, as they sat down with their coffee pot of bran to remake that uniform, it was burdensome in many ways the men’s wasn’t.

Thanks for the enjoyable article – very funny about boiling old cigar stumps in a dirty coffee pot. In a cache of family Civil War letters, I found quite a few mentions of coffee. When stationed in their home state of South Carolina, my forebears, the Jeffers brothers, often received care packages from their father, a resourceful merchant:

(From Spann Jeffers to his sister)

Camp RMR & H.A., McPhersonville, August 2nd 1863

Dear Gussie…Since Henry returned from Home we have been living extravagantly. Butter, waffles, biscuit, and good bacon have taken the place of Corn bread and Rice. We are more fortunate than most messes in always having a supply of coffee. We never drink it except in the morning, so a small quantity lasts for some time. My little coffee pot is never forgotten when starting on picket. Henry carries his, already drawn, in a bottle and we are well repaid for our trouble for if we go without it a headache during the next day is the sure consequence.

Then when stationed in Virginia (under General Martin Gary) during the Petersburg-Richmond campaign, the brothers might get some coffee as a bonus for fighting beside General Lee’s troops:

(From Henry Jeffers to his father)

Camp 7th Regt., June 20th 1864

Dear Pa, …The health of the men is pretty good. From living so long and constantly on Corn Bread & Bacon, some have Diarrhea, but we will get some flour soon and as we have been doing such active service with Genl Lees Army we [get] Sugar & Coffee tomorrow.

You could have simply purchased chicory coffee from New Orleans, but I suppose that would have not been as adventurous. To this day, chicory coffee is about 1/3 chicory and 2/3 coffee. It should not be a surprise that coffee was so important to soldiers. It still is today. I basically became a dedicated coffee drinker after having to pull night shift so many times while doing Army training. There is just not much to do during those long, mostly quiet nights.

Tom

I’m personally a big fan of chicory coffee and you can buy it in the local grocery stores down here (Florida). Of course, the best kind comes from Cafe DuMonde in New Orleans. It just hits different.

Thank you for experimenting for us! I’ve been curious about some other coffee alternatives myself.