John Wesley Powell and the Wounds of War

In the hundreds of pages Major John Wesley Powell wrote about his postbellum career as an explorer of the American West, he seldom mentioned the injury he sustained at the battle of Shiloh. During the fighting at Pittsburgh Landing in April 1862, Powell was hit by a bullet in his right forearm. The wound required the arm to be amputated below the elbow, leaving the 28-year-old Powell with an affliction that caused him excruciating pain for the remainder of his life. He lived to be 68.

In the hundreds of pages Major John Wesley Powell wrote about his postbellum career as an explorer of the American West, he seldom mentioned the injury he sustained at the battle of Shiloh. During the fighting at Pittsburgh Landing in April 1862, Powell was hit by a bullet in his right forearm. The wound required the arm to be amputated below the elbow, leaving the 28-year-old Powell with an affliction that caused him excruciating pain for the remainder of his life. He lived to be 68.

Powell was one of thousands of veterans who emerged from the Civil War less than whole. Historians have estimated that some 60,000 soldiers underwent amputation operations during the conflict, with some 45,000 surviving their surgeries and the war.

In recent years, historians have begun the work of understanding how these wounds impacted the lives of veterans. Identified by some as a “Dark Turn” in the study of the conflict, scholars writing about these difficult subjects often focus on the lifelong trauma such wounds and operations could cause. It is a hard history to capture. PTSD, as we understand it in 2022, was not an available diagnosis for Civil War veterans, though many scholars have insisted that Civil War soldiers did suffer psychological consequences from their service. Further complicating the quest to better understand the war’s medical consequences – many veterans who carried wartime wounds with them followed Powell’s model. An amputated limb was not a public concern, it was a private affliction.

Despite their injuries, former soldiers such as Powell set their bodies and minds to the future, binding up their wounds just as the nation had been instructed to do by the martyred sixteenth president, Abraham Lincoln. Powell looked to the West for his salvation—and, after 1867, led multiple expeditions to map and explore Rocky Mountains and the Green and Colorado rivers. The injury he carried with him did not seem an obstacle to Powell’s success as a geologist and explorer. Or, if it was, Powell did not think it worth mentioning. In his narrative of his first expedition down the Colorado River and through the Grand Canyon in 1869, Powell neglected to tell readers that he was missing his right arm below the elbow, save for the preface, in which he noted he was a “maimed” man.

According to Elizabeth Bacon Custer, Powell’s stoic approach was common among wounded veterans of the Civil War. In recounting injuries received by men who campaigned with her husband, George Armstrong Custer, she celebrated the resilience veterans displayed in their postbellum pursuits. “[A]nother of our military family,” she told her readers, “invalided by his eleven months’ confinement in Libbie Prison, set his wan, white face toward the uncertain future before him, and began his bread-winning, his soul undaunted by his disabled body.” Describing a second man, Libbie exclaimed “what a brave boy he was!” The young man, she explained, “carried always, does now, a shattered arm, torn by a bullet while he was riding beside General Custer in Virginia,” but assured her reader the injury “did not keep him from giving his splendid energy, his best and truest patriotism, to his country down in Texas even after the war, for he rode on long, exhausting campaigns after the Indians, his wound bleeding, his life sapped, his vitality slipping away with the pain that never left him day or night.”[1] What Libbie described was precisely how Powell wrote, as if the injury did not exist, and did not compromise his quality of life.

Powell’s tendency to ignore his injury in his professional writing did not mean the wound failed to trouble him. Owing to poor surgical technique during his operation, Powell suffered from severe nerve pain for his entire life. [2] While participating in the Vicksburg campaign, Powell contracted dysentery, dropping to a weight of about 100 pounds. The decline in Powell’s health was aggravated by the exposed nerves and he lift Vicksburg for Detroit where a second surgery allowed him enough relief to return to action, and take part in the fighting for Atlanta and in the battle of Nashville.

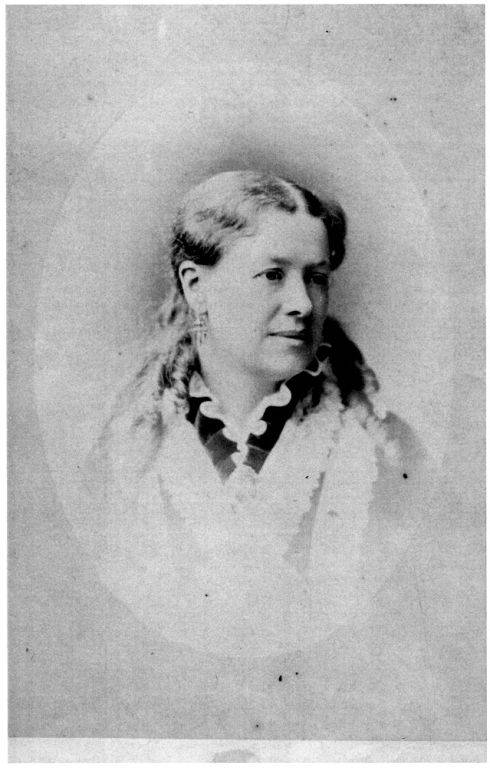

The only thing that sustained Powell, according to his early biographers and contemporaries, was the care of his wife Emma, who he had married just a few months prior to his wounding.Emma was present at the hospital in Savannah, Tennessee where the operation was undertaken, as she had joined Powell with his battery after their wedding. After Powell’s wounding, he requested permission from his commanding officer, Ulysses S. Grant, to have his wife accompany him for the remainder of the war. Grant sent Emma a perpetual pass. She stayed with Powell as often as she could, until 1865, when he finally requested to be discharged from the Union Army.

Emma cared for her husband and his wound for the remainder of his life. When Powell died in 1902, the United States Congress passed a special bill to grant Emma a pension, because the Pension Bureau had denied her request, asserting she could not prove her husband’s wound was of an army origin. In the citation recognizing her qualifications for a pension, the nation’s legislators offered a clue as to why Powell was able to achieve all that he did, despite the amputation of his arm:

“During most of his military service she kept near him and it is due to a large extent to her loving care and intelligent nursing that Major Powell was able so soon after the amputation of his right arm to rejoin his command in the field and render valuable and conspicuous service to his country in his campaigns during the nearly three years of his army life which followed. At the siege of Vicksburg she not only ministered to her husband’s wants but also gave her best services in the hospitals at Vicksburg to other wounded officers, being retained within the lines by special direction of General Grant. [3]

Though it must always be conjecture — and cognizant of the fact that the labor of women like Emma Dean Powell is only beginning to be recognized as vital to the Union War effort and critical to the care of the many veterans who suffered privately in their homes from wounds both seen and unseen, attended by wives, sisters, and mothers in their darkest moments — perhaps Powell was fortunate to have a partner who could support him, so that when he wrote about his lifetime of adventure he could simply gloss over the injury that might reasonably have prevented him from performing many of the feats he accomplished.

It is notable that, too, that Elizabeth Custer took time out of her narrative of postbellum military life to recognize the silent struggles of wounded Civil War veterans. Her husband, George, made no such allusions in his collected writings–though he ostensibly spent more time with the men to whom Libbie referred.

There are likely multiple of explanations, medical, cultural, social, political, and economic, that veterans bore their wartime wounds in private silence. The cultural mores of the Victorian Era and nineteenth-century ideas about masculinity and manhood almost certainly played a role. The curious silences regarding how wartime injuries truly impacted the functioning of American society after 1865 will continue to be fertile ground for historians seeking to understand the Civil War and its long-term consequences. As public interest in the war’s scientific and medical histories continues to expand, I will eagerly await new ideas about how veterans navigated the postbellum world while nursing their wartime wounds.

[1] Elizabeth Bacon Custer, Tenting on the Plains (1887; reprint, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971), 299.

[2] Powell’s surgeon was William D. Medcalfe of the 49th Illinois Volunteer Infantry, who was a druggist, not a surgeon, by trade.

[3] “Emma Dean Powell,” 57th Cong. 2nd Sess., Senate Report No. 2302

An excellent article on, as you suggest, a postwar issue that remains obscure. Thank you!

An excellent post!

Good post. In my Shiloh work I discuss Powell’s wounding and I did find an account of it in a letter that is at Shiloh’s archives.

Where did you get the image of him in 1865? I may include it in my book.

Last thing to note, Grant took a liking to Emma Powell when she came to visit him after Shiloh.